Age of trees in the Siberian taiga. And the forest is mysterious

It was the wary attitude towards Alexei Kungurov’s statements regarding Perm forests and clearings, at one of his conferences, that prompted me to conduct this research. Well, of course! There was a mysterious hint of hundreds of kilometers of clearings in the forests and their age. I personally was hooked by the fact that I walk through the forest quite often and quite far, but I didn’t notice anything unusual.

And this time the amazing feeling was repeated - the more you understand, the more new questions appear. I had to re-read a lot of sources, from materials on forestry of the 19th century, to the modern “Instructions for carrying out forest management in the forest fund of Russia.” This did not add clarity, rather the opposite. But there was confidence that things are dirty here.

First amazing fact

, which was confirmed - dimension of the quarter network. A quarter network, by definition, is “a system of forest quarters created on forest fund lands for the purpose of inventorying the forest fund, organizing and maintaining forestry and forest management.” The quarterly network consists of quarterly clearings. This is a straight strip cleared of trees and shrubs (usually up to 4 m wide), laid in the forest to mark the boundaries of forest blocks. During forest management, quarterly clearings are cut and cleared to a width of 0.5 m, and their expansion to 4 m is carried out in subsequent years by forestry workers.

In the picture you can see what these clearings look like in Udmurtia. The picture was taken from the program Google Earth(see Fig. 2). The blocks are rectangular in shape. For measurement accuracy, a segment of 5 blocks wide is marked. She made up 5340

m, which means that the width of 1 quarter is 1067

meters, or exactly 1 way mile. The quality of the picture leaves much to be desired, but I myself walk along these clearings all the time, and what you see from above I know well from the ground. Until that moment, I was firmly convinced that all these forest roads were the work of Soviet foresters. But what the hell did they need? mark the quarterly network in versts?

I checked. The instructions state that blocks should be 1 by 2 km in size. The error at this distance is allowed no more than 20 meters. But 20 is not 340. However, all forest management documents stipulate that if block network projects already exist, then you should simply link to them. This is understandable; the work of laying clearings is a lot of work to redo.

Today there are already machines for cutting down glades (see Fig. 3), but we should forget about them, since almost the entire forest fund of the European part of Russia, plus part of the forest beyond the Urals, approximately to Tyumen, is divided into a mile-long block network. There are also kilometer-long ones, of course, because in the last century foresters have also been doing something, but mostly it’s the mile-long one. In particular, in Udmurtia there are no kilometer-long clearings. This means that the design and practical construction of a block network in most of the forest areas of the European part of Russia were completed no later than 1918. It was at this time that the metric system of measures was adopted for mandatory use in Russia, and the mile gave way to the kilometer.

It turns out made with axes and jigsaws, if we, of course, correctly understand historical reality. Considering that the forest area of the European part of Russia is the size of about 200 million hectares, this is titanic work. The calculation shows that the total length of the clearings is about 3 million km. For clarity, imagine the first lumberjack, armed with a saw or an ax. In a day he will be able to clear on average no more than 10 meters of clearing. But we must not forget that this work can be carried out mainly in winter. This means that even 20,000 lumberjacks, working annually, would create our excellent verst quarter network for at least 80 years.

But there has never been such a number of workers involved in forest management. Based on articles from the 19th century, it is clear that there were always very few forestry specialists, and the funds allocated for these purposes could not cover such expenses. Even if we imagine that for this purpose peasants were driven from surrounding villages to do free work, it is still unclear who did this in the sparsely populated areas of the Perm, Kirov, and Vologda regions.

After this fact, it is no longer so surprising that the entire quarterly network is tilted by about 10 degrees and is directed not towards the geographic north pole, but, apparently, towards magnetic(the markings were carried out using a compass, and not a GPS navigator), which at that time should have been located approximately 1000 kilometers towards Kamchatka. And it’s not so confusing that the magnetic pole, according to official data from scientists, has never been there from the 17th century to the present day. It’s no longer scary that even today the compass needle points in approximately the same direction in which the quarterly network was made before 1918. All this cannot happen anyway! All logic falls apart.

But it is there. And in order to finish off the consciousness clinging to reality, I inform you that all this equipment also needs to be serviced. According to the norms, a complete audit takes place every 20 years. If it passes at all. And during this period of time, the “forest user” must monitor the clearings. Well, if anyone was watching in Soviet times, it’s unlikely that over the past 20 years. But the clearings are not overgrown. There is a windbreak, but there are no trees in the middle of the road. But in 20 years, a pine seed that accidentally fell to the ground, of which billions are sown annually, grows up to 8 meters in height. Not only are the clearings not overgrown, you won’t even see stumps from periodic clearings. This is all the more striking in comparison with power lines, which special teams regularly clear of overgrown bushes and trees.

This is what typical clearings in our forests look like. Grass, sometimes there are bushes, but no trees. There are no signs of regular maintenance (see Fig. 4 and Fig. 5).

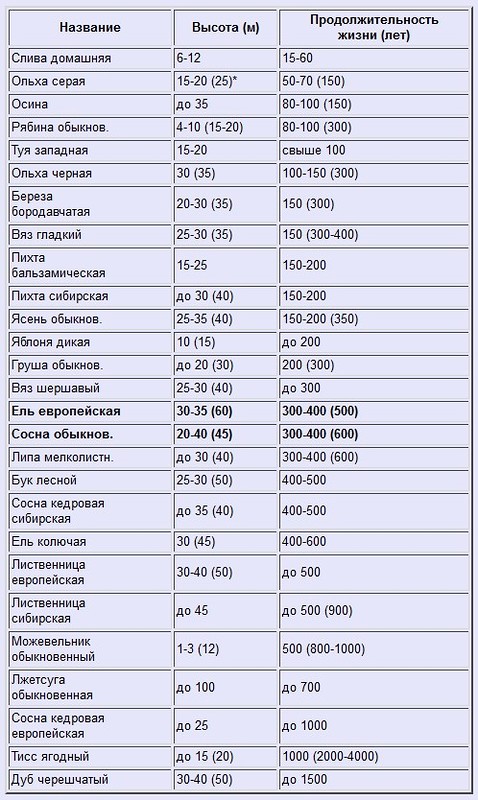

Second big mystery- This the age of our forest, or trees in this forest. In general, let's go in order. First, let's figure out how long a tree lives. Here is the corresponding table.

| Name | Height (m) | Life expectancy (years) |

| Homemade plum | 6-12 | 15-60 |

| Gray alder | 15-20 (25)* | 50-70 (150) |

| Aspen | up to 35 | 80-100 (150) |

| Mountain ash | 4-10 (15-20) | 80-100 (300) |

| Thuja occidentalis | 15-20 | over 100 |

| Black alder | 30 (35) | 100-150 (300) |

| Birch warty | 20-30 (35) | 150 (300) |

| Smooth elm | 25-30 (35) | 150 (300-400) |

| Balsam fir | 15-25 | 150-200 |

| Siberian fir | up to 30 (40) | 150-200 |

| Common ash | 25-35 (40) | 150-200 (350) |

| Apple tree wild | 10 (15) | up to 200 |

| Common pear | up to 20 (30) | 200 (300) |

| Rough elm | 25-30 (40) | up to 300 |

| Norway spruce | 30-35 (60) | 300-400 (500) |

| Scots pine | 20-40 (45) | 300-400 (600) |

| Small-leaved linden | up to 30 (40) | 300-400 (600) |

| Beech | 25-30 (50) | 400-500 |

| Siberian cedar pine | up to 35 (40) | 400-500 |

| Prickly spruce | 30 (45) | 400-600 |

| European larch | 30-40 (50) | up to 500 |

| Siberian larch | up to 45 | up to 500 (900) |

| Common juniper | 1-3 (12) | 500 (800-1000) |

| Common falsesuga | up to 100 | up to 700 |

| European cedar pine | up to 25 | up to 1000 |

| Yew berry | up to 15 (20) | 1000 (2000-4000) |

| English oak | 30-40 (50) | up to 1500 |

In different sources, the figures differ slightly, but not significantly. Pine and spruce should survive under normal conditions up to 300...400 years. You begin to understand how absurd everything is only when you compare the diameter of such a tree with what we see in our forests. A 300-year-old spruce should have a trunk with a diameter of about 2 meters. Well, like in a fairy tale. The question arises: Where are all these giants? No matter how much I walk through the forest, I haven’t seen anything thicker than 80 cm. There aren’t many of them. There are individual copies ( in Udmurtia - 2 pines) which reach 1.2 m, but their age is also no more than 200 years. In general, how does the forest live? Why do trees grow or die in it?

It turns out there is a concept "natural forest". This is a forest that lives its own life - it has not been cut down. He has distinguishing feature- low crown density from 10 to 40%. That is, some trees were already old and tall, but some of them fell affected by fungus or died, losing competition with their neighbors for water, soil and light. Large gaps form in the forest canopy. A lot of light begins to get there, which is very important in the forest struggle for existence, and young animals begin to actively grow. Therefore, a natural forest consists of different generations, and crown density is the main indicator of this.

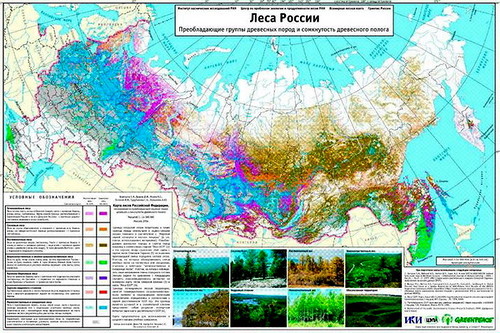

But if the forest has been clear-cut, then new trees grow simultaneously for a long time, the crown density is high, more than 40%. Several centuries will pass, and if the forest is not touched, then the struggle for a place in the sun will do its job. It will become natural again. Do you want to know how much natural forest there is in our country that is not affected by anything? Please, map of Russian forests (see Fig. 6).

Bright shades indicate forests with a high canopy density, that is, these are not “natural forests.” And these are the majority. The entire European part is indicated in rich blue. This is as shown in the table: “Small-leaved and mixed forests. Forests with a predominance of birch, aspen, gray alder, often with an admixture coniferous trees or with individual areas of coniferous forests. Almost all of them are derivative forests, formed on the site of primary forests as a result of logging, clearing, forest fires...”

You don’t have to stop at the mountains and tundra zone; there the rarity of crowns may be due to other reasons. But the plains and middle lane covers clearly a young forest. How young? Go and check it out. It is unlikely that you will find a tree in the forest that is older than 150 years. Even a standard drill for determining the age of a tree is 36 cm long and is designed for a tree age of 130 years. How does this explain forest science? Here's what they came up with:

“Forest fires are a fairly common phenomenon for most of the taiga zone European Russia. Moreover: Forest fires in the taiga are so common that some researchers consider the taiga as many burnt areas of different ages - more precisely, many forests formed on these burnt areas. Many researchers believe that forest fires are, if not the only, then at least the main natural mechanism for forest renewal, replacing old generations of trees with young ones..."

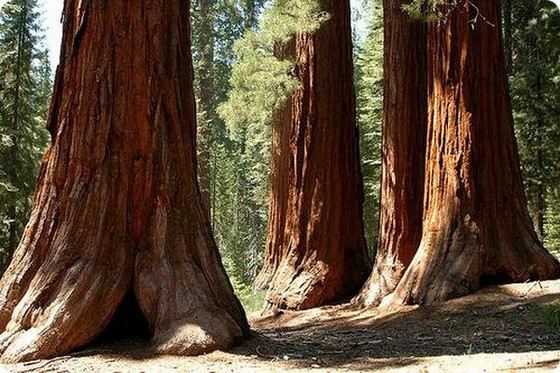

All this is called . That's where the dog is buried. The forest was burning, and was practically burning everywhere. And this, according to experts, is the main reason for the low age of our forests. Not fungus, not bugs, not hurricanes. Our entire taiga is in burnt areas, and after a fire, what remains is the same as after clear cutting. From here high crown density throughout almost the entire forest zone. Of course, there are exceptions - truly untouched forests in the Angara region, on Valaam and, probably, somewhere else in the vast expanses of our vast Motherland. It's really fabulous there big trees in its entirety. And although these are small islands in the vast sea of taiga, they prove that the forest can be like this.

What is so common about forest fires that over the past 150...200 years they have burned the entire forest area of 700 million hectares? Moreover, according to scientists, in some checkerboard pattern observing the sequence, and certainly at different times?

First we need to understand the scale of these events in space and time. The fact that the main age of old trees in the bulk of forests is at least 100 years, suggests that the large-scale fires that so rejuvenated our forests occurred over a period of no more than 100 years. Translating into dates, for one only 19th century. For this it was necessary burn 7 million hectares of forest annually.

Even as a result of large-scale forest arson in the summer of 2010, which all experts called catastrophic in volume, only 2 million hectares. It turns out there is nothing “so ordinary” about this. The last justification for such a burned-out past of our forests could be the tradition of slash-and-burn agriculture. But how, in this case, can we explain the state of the forest in places where traditionally agriculture was not developed? In particular, in Perm region? Moreover, this method of farming involves labor-intensive cultural use of limited areas of forest, and not at all the uncontrolled burning of large tracts in the hot summer season, and with the wind.

Having gone through everything possible options, we can say with confidence that scientific concept “dynamics of random violations” nothing in real life not justified, and is myth, intended to disguise the inadequate state of the current forests of Russia, and therefore events that led to this.

We will have to admit that our forests either burned intensely (beyond any norm) and constantly throughout the 19th century (which in itself is inexplicable and not recorded anywhere), or burned down at one time as a result some incident, which is why the scientific world furiously denies it, having no arguments other than the fact that nothing like this is recorded in official history.

To all this we can add that there were clearly fabulously large trees in old natural forests. It has already been said about the preserved areas of the taiga. It is worth giving an example regarding deciduous forests. The Nizhny Novgorod region and Chuvashia have a very favorable climate for deciduous trees. grows there great amount oak trees But, again, you won’t find old copies. The same 150 years, no older. Older single copies are all the same. There is a photograph at the beginning of the article the largest oak tree in Belarus. It grows in Belovezhskaya Pushcha (see Fig. 1). Its diameter is about 2 meters, and its age is estimated at 800 years, which, of course, is very conditional. Who knows, maybe he somehow survived the fires, this happens. The largest oak tree in Russia is considered to be a specimen growing in the Lipetsk region. According to conventional estimates, he 430 years(see Fig. 7).

A special theme is bog oak. This is the one that is extracted mainly from the bottom of rivers. My relatives from Chuvashia told me that they pulled out huge specimens up to 1.5 m in diameter from the bottom. AND there were a lot of them(see Fig. 8). This indicates the composition of the former oak forest, the remains of which lie at the bottom. This means that nothing prevents current oak trees from growing to such sizes. What, maybe earlier? “dynamics of random violations” did it work in a special way in the form of thunderstorms and lightning? No, everything was the same. So it turns out that the current forest simply has not yet reached maturity.

Let's summarize what we learned from this study. There are a lot of contradictions between the reality that we see with our own eyes and the official interpretation of the relatively recent past:

- There is a developed neighborhood network in a huge space, which was designed in versts and was laid no later than 1918. The length of the clearings is such that 20,000 lumberjacks, using manual labor, would take 80 years to create it. The clearings are maintained very irregularly, if at all, but they do not become overgrown.

- On the other side, according to historians and surviving articles on forestry, there was no funding of comparable scale and the required number of forestry specialists at that time. There was no way to recruit such a quantity of free labor. There was no mechanization to facilitate this work. We need to choose: either our eyes deceive us, or The 19th century wasn't like that at all, as historians tell us. In particular, there could be mechanization, commensurate with the described tasks (What interesting purpose could this steam engine from the film “The Barber of Siberia” (see Fig. 9) be intended for? Or is Mikhalkov a completely unimaginable dreamer?).

There could also have been less labor-intensive, effective technologies for laying and maintaining clearings, which have been lost today (some distant analogue of herbicides). It is probably stupid to say that Russia has not lost anything since 1917. Finally, it is possible that clearings were not cut, but trees were planted in blocks in areas destroyed by fire. This is not such nonsense compared to what science tells us. Although doubtful, it at least explains a lot.

- Our forests are much younger the natural lifespan of the trees themselves. This is evidenced by the official map of Russian forests and our eyes. The age of the forest is about 150 years, although pine and spruce under normal conditions grow up to 400 years and reach 2 meters in thickness. There are also separate areas of forest with trees of similar age.

According to experts, all our forests are burnt. It is the fires in their opinion, do not give trees a chance to live to their natural age. Experts do not even allow the thought of the simultaneous destruction of vast expanses of forest, believing that such an event could not go unnoticed. In order to justify this ashes, official science adopted the theory of “dynamics of random disturbances.” This theory suggests that forest fires are considered a common occurrence, destroying (according to some incomprehensible schedule) up to 7 million hectares of forest per year, although in 2010 even 2 million hectares destroyed as a result of deliberate forest fires were called catastrophe.

You need to select: either our eyes are deceiving us again, or some grandiose events of the 19th century with particular impudence were not reflected in official version our past, how could not fit in there

Another notch for memory. Is everything presented honestly and objectively in the official history?

Most of our forests are young. They are between a quarter and a third of their lives. Apparently, in the 19th century certain events occurred that led to the almost total destruction of our forests. Our forests keep big secrets...

It was a wary attitude towards Alexei Kungurov’s statements about Perm forests and clearings at one of his conferences that prompted me to conduct this research. Well, of course! There was a mysterious hint of hundreds of kilometers of clearings in the forests and their age. I personally was hooked by the fact that I walk through the forest quite often and quite far, but I didn’t notice anything unusual.

And this time the amazing feeling was repeated - the more you understand, the more new questions appear. I had to re-read a lot of sources, from materials on forestry of the 19th century to modern “ Instructions for carrying out forest management in the Russian forest fund" This did not add clarity, rather the opposite. But there was confidence that things are dirty here.

The first surprising fact that was confirmed is the dimension quarterly network. By definition, a quarterly network is “ A system of forest blocks created on forest lands for the purpose of inventorying the forest fund, organizing and maintaining forestry and forest management».

The quarterly network consists of quarterly clearings. This is a straight strip cleared of trees and shrubs (usually up to 4 m wide), laid in the forest to mark the boundaries of forest blocks. During forest management, quarterly clearings are cut and cleared to a width of 0.5 m, and their expansion to 4 m is carried out in subsequent years by forestry workers.

Fig.2

In the picture you can see what these clearings look like in Udmurtia. The picture was taken from the Google Earth program ( see Fig.2). The blocks are rectangular in shape. For measurement accuracy, a segment of 5 blocks wide is marked. It was 5340 m, which means that the width of 1 block is 1067 meters, or exactly 1 way mile. The quality of the picture leaves much to be desired, but I myself walk along these clearings all the time, and what you see from above I know well from the ground. Until that moment, I was firmly convinced that all these forest roads were the work of Soviet foresters. But why the hell did they need to mark out the neighborhood network? in versts?

I checked. The instructions state that blocks should be 1 by 2 km in size. The error at this distance is allowed no more than 20 meters. But 20 is not 340. However, all forest management documents stipulate that if block network projects already exist, then you should simply link to them. This is understandable; the work of laying clearings is a lot of work to redo.

Fig.3

Today there are already machines for cutting down glades (see. Fig.3), but we should forget about them, since almost the entire forest fund of the European part of Russia, plus part of the forest beyond the Urals, approximately to Tyumen, is divided into a verst block network. There are also kilometer-long ones, of course, because in the last century foresters have also been doing something, but mostly it’s the mile-long one. In particular, in Udmurtia there are no kilometer-long clearings. This means that the design and practical construction of a block network in most of the forest areas of the European part of Russia were completed no later than 1918. It was at this time that the metric system of measures was adopted for mandatory use in Russia, and the mile gave way to the kilometer.

It turns out made with axes and jigsaws, if we, of course, correctly understand historical reality. Considering that the forest area of the European part of Russia is about 200 million hectares, this is titanic work. Calculations show that the total length of the clearings is about 3 million km. For clarity, imagine the first lumberjack, armed with a saw or an ax. In a day he will be able to clear on average no more than 10 meters of clearing. But we must not forget that this work can be carried out mainly in winter. This means that even 20,000 lumberjacks, working annually, would create our excellent verst quarter network for at least 80 years.

But there has never been such a number of workers involved in forest management. Based on articles from the 19th century, it is clear that there were always very few forestry specialists, and the funds allocated for these purposes could not cover such expenses. Even if we imagine that for this purpose peasants were driven from surrounding villages to do free work, it is still unclear who did this in the sparsely populated areas of the Perm, Kirov, and Vologda regions.

After this fact, it is no longer so surprising that the entire quarterly network is tilted by about 10 degrees and is directed not towards the geographic north pole, but, apparently, towards the magnetic one ( The markings were carried out using a compass, not a GPS navigator), which should have been located approximately 1000 kilometers towards Kamchatka at that time. And it’s not so confusing that the magnetic pole, according to official data from scientists, has never been there from the 17th century to the present day. It’s no longer scary that even today the compass needle points in approximately the same direction in which the quarterly network was made before 1918. All this cannot happen anyway! All logic falls apart.

But it is there. And in order to finish off the consciousness clinging to reality, I inform you that all this equipment also needs to be serviced. According to the norms, a complete audit takes place every 20 years. If it passes at all. And during this period of time, the “forest user” must monitor the clearings. Well, if anyone was watching in Soviet times, it’s unlikely that over the past 20 years. But the clearings were not overgrown. There is a windbreak, but there are no trees in the middle of the road.

But in 20 years, a pine seed that accidentally fell to the ground, of which billions are sown annually, grows up to 8 meters in height. Not only are the clearings not overgrown, you won’t even see stumps from periodic clearings. This is all the more striking in comparison with power lines, which special teams regularly clear of overgrown bushes and trees.

Fig.4

This is what typical clearings in our forests look like. Grass, sometimes there are bushes, but no trees. There are no signs of regular maintenance (see. Fig.4 And Fig.5).

Fig.5

The second big mystery is the age of our forest, or the trees in this forest. In general, let's go in order. First, let's figure out how long a tree lives. Here is the corresponding table.

|

* In brackets are the height and life expectancy in particularly favorable conditions.

In different sources, the figures differ slightly, but not significantly. Pine and spruce should live up to 300...400 years under normal conditions. You begin to understand how absurd everything is only when you compare the diameter of such a tree with what we see in our forests. A 300-year-old spruce should have a trunk with a diameter of about 2 meters. Well, like in a fairy tale. The question arises: Where are all these giants? No matter how much I walk through the forest, I haven’t seen anything thicker than 80 cm. There aren’t many of them. There are individual copies (in Udmurtia - 2 pines) which reach 1.2 m, but their age is also no more than 200 years.

In general, how does the forest live? Why do trees grow or die in it?

It turns out that there is a concept of “natural forest”. This is a forest that lives its own life - it has not been cut down. It has a distinctive feature - low crown density from 10 to 40%. That is, some trees were already old and tall, but some of them fell affected by fungus or died, losing competition with their neighbors for water, soil and light. Large gaps form in the forest canopy. A lot of light begins to get there, which is very important in the forest struggle for existence, and young animals begin to actively grow. Therefore, a natural forest consists of different generations, and crown density is the main indicator of this.

But if the forest was clear-cut, then new trees grow simultaneously for a long time, the crown density is high, more than 40%. Several centuries will pass, and if the forest is not touched, then the struggle for a place in the sun will do its job. It will become natural again. Do you want to know how much natural forest there is in our country that is not affected by anything? Please, map of Russian forests (see. Fig.6).

Fig.6

Bright shades indicate forests with a high canopy density, that is, these are not “natural forests.” And these are the majority. The entire European part is indicated in rich blue. This is as indicated in the table: " Small-leaved and mixed forests. Forests with a predominance of birch, aspen, gray alder, often with an admixture of coniferous trees or with separate areas of coniferous forests. Almost all of them are derivative forests, formed on the site of primary forests as a result of logging, clearing, and forest fires».

You don’t have to stop at the mountains and tundra zone; there the rarity of crowns may be due to other reasons. But the plains and middle zone are covered clearly a young forest. How young? Go and check it out. It is unlikely that you will find a tree in the forest that is older than 150 years. Even a standard drill for determining the age of a tree is 36 cm long and is designed for a tree age of 130 years. How does forest science explain this? Here's what they came up with:

« Forest fires are a fairly common phenomenon for most of the taiga zone of European Russia. Moreover: forest fires in the taiga are so common that some researchers consider the taiga as many burnt areas of different ages - more precisely, many forests formed on these burnt areas. Many researchers believe that forest fires are, if not the only, then at least the main natural mechanism of forest renewal, replacing old generations of trees with young ones…»

All this is called " dynamics of random violations" That's where the dog is buried. The forest was burning, and burning almost everywhere. And this, according to experts, is the main reason for the low age of our forests. Not fungus, not bugs, not hurricanes. Our entire taiga is in burnt areas, and after a fire, what remains is the same as after clear cutting. Hence the high crown density throughout almost the entire forest zone. Of course, there are exceptions - truly untouched forests in the Angara region, on Valaam and, probably, somewhere else in the vast expanses of our vast Motherland. There are really fabulously large trees there in their mass. And although these are small islands in the vast sea of taiga, they prove that a forest can be like that.

What is so common about forest fires that over the past 150...200 years they have burned the entire forest area of 700 million hectares? Moreover, according to scientists, in a certain checkerboard order, observing the order, and certainly at different times?

First we need to understand the scale of these events in space and time. The fact that the main age of old trees in the bulk of forests is at least 100 years old suggests that the large-scale burns that so rejuvenated our forests occurred over a period of no more than 100 years. Translating into dates, for the 19th century alone. For this 7 million hectares of forest had to be burned annually.

Even as a result of large-scale forest arson in the summer of 2010, which all experts called catastrophic in volume, burned only 2 million hectares. It turns out nothing" so ordinary"This is not the case. The last justification for such a burned-out past of our forests could be the tradition of slash-and-burn agriculture. But how, in this case, can we explain the state of the forest in places where traditionally agriculture was not developed? In particular, in the Perm region? Moreover, this method of farming involves labor-intensive cultural use of limited areas of forest, and not at all the uncontrolled burning of large tracts in the hot summer season, and with the wind.

Having gone through all possible options, we can say with confidence that the scientific concept “ dynamics of random violations“is not substantiated by anything in real life, and is a myth intended to disguise the inadequate state of the current forests of Russia, and therefore the events that led to this.

We will have to admit that our forests are either beyond any norm) and constantly burned throughout the 19th century ( which in itself is inexplicable and not recorded anywhere), or burned at the same time as a result of some incident, which the scientific world vehemently denies, having no arguments other than that in official nothing like this is recorded in history.

To all this we can add that there were clearly fabulously large trees in old natural forests. It has already been said about the preserved areas of the taiga. It is worth giving an example regarding deciduous forests. The Nizhny Novgorod region and Chuvashia have a very favorable climate for deciduous trees. There are a huge number of oak trees growing there. But, again, you won’t find old copies. The same 150 years, no older.

Older single copies are all the same. At the beginning of the article there is a photograph of the largest oak tree in Belarus. It grows in Belovezhskaya Pushcha (see. Fig.1). Its diameter is about 2 meters, and its age is estimated at 800 years, which, of course, is very arbitrary. Who knows, maybe he somehow survived the fires, this happens. The largest oak tree in Russia is considered to be a specimen growing in the Lipetsk region. According to conventional estimates, he is 430 years old (see. Fig.7).

Fig.7

A special theme is bog oak. This is the one that is extracted mainly from the bottom of rivers. My relatives from Chuvashia told me that they pulled out huge specimens up to 1.5 m in diameter from the bottom. And there were many of them (see Fig.8). This indicates the composition of the former oak forest, the remains of which lie at the bottom. This means that nothing prevents current oak trees from growing to such sizes. Did the “dynamics of random disturbances” in the form of thunderstorms and lightning work in some special way before? No, everything was the same. So it turns out that the current forest simply has not yet reached maturity.

Fig.8

Let's summarize what we learned from this study. There are a lot of contradictions between the reality that we see with our own eyes and the official interpretation of the relatively recent past:

There is a developed neighborhood network over a vast area, which was designed in miles and was laid no later than 1918. The length of the clearings is such that 20,000 lumberjacks, using manual labor, would take 80 years to create it. The clearings are maintained very irregularly, if at all, but they do not become overgrown.

On the other hand, according to historians and surviving articles on forestry, there was no funding of comparable scale and the required number of forestry specialists at that time. There was no way to recruit such a quantity of free labor. There was no mechanization to facilitate this work.

We need to choose: either our eyes deceive us, or the 19th century was not at all what historians tell us. In particular, there could be mechanization commensurate with the tasks described. What interesting purpose could this steam engine from the film " Siberian barber" (cm. Fig.9). Or is Mikhalkov a completely unimaginable dreamer?

Fig.9

There could also have been less labor-intensive, efficient technologies for laying and maintaining clearings, which are lost today ( some distant analogue of herbicides). It is probably stupid to say that Russia has not lost anything since 1917. Finally, it is possible that clearings were not cut, but trees were planted in blocks in areas destroyed by fire. This is not such nonsense compared to what science tells us. Although doubtful, it at least explains a lot.

Our forests are much younger than the natural lifespan of the trees themselves. This is evidenced by the official map of Russian forests and our eyes. The age of the forest is about 150 years, although pine and spruce under normal conditions grow up to 400 years and reach 2 meters in thickness. There are also separate areas of forest with trees of similar age.

According to experts, all our forests are burnt. It is fires, in their opinion, that do not give trees a chance to live to their natural age. Experts do not even allow the thought of the simultaneous destruction of vast expanses of forest, believing that such an event could not go unnoticed. In order to justify this ashes, official science adopted the theory “ dynamics of random violations" This theory suggests that forest fires that destroy ( according to some strange schedule) up to 7 million hectares of forest per year, although in 2010 even 2 million hectares, destroyed as a result of deliberate forest fires, were called a disaster.

We need to choose: either our eyes are deceiving us again, or some grandiose events of the 19th century with particular impudence were not reflected in the official version of our past, as it didn’t fit into it nor Great Tartaria, nor the Great Northern Route. Atlantis with a fallen moon and even then they didn’t fit. One-time destruction 200...400 million hectares forests are even easier to imagine and hide than the undying, 100-year-old fire proposed for consideration by science.

So what is the age-old sadness about? Belovezhskaya Pushcha? Is it not about those severe wounds of the earth that the young forest covers? After all, gigantic fires by themselves don't happen...

There are many trees with record life expectancy in Russia, and there are some in Moscow. It is interesting to find out where many old trees grow, as well as details about the oldest tree on the planet.

The oldest tree in Russia

In Russia there is a register where all the oldest trees growing in the country are entered. Almost twenty of the oldest trees have the status of protected natural sites. Each old tree is inspected and studied before being included in the register. This is done by a commission that includes botanists, forest scientists, ecologists, and forest pathologists. During the research, the species, condition of the tree and its age are determined. The oldest trees are protected and, if required, measures are taken to promote the preservation of the tree. In addition, a sign is installed indicating the status and age of the centenarian.In Russia, the register includes an oak tree growing in Chuvashia that is four hundred and eighty years old, a four hundred year old oak tree on the Don, and a plane tree from Dagestan that is seven hundred years old. There are also several Cajander larches, growing in a whole area in Yakutia, ranging in age from seven hundred and fifty to eight hundred and eighty-five years. The list also included the “Grunwald oak” growing in the Kaliningrad region, which is more than eight hundred years old.

The oldest tree grows in Yakutia. This is a larch tree that is eight hundred and eighty-five years old. Interestingly, it is not at all large in size. So its diameter at the level of a person’s chest is only twenty-five centimeters, and its height is no more than nine meters. Such modest sizes are associated with complex climatic conditions in the place where the long-lived tree grows. The height of the tree increases by no more than 0.22 mm per year.

Among the growing larches in Yakutia, many dry trunks have been preserved. Among them, a tree was discovered that grew from the year three hundred and ten to the year one thousand two hundred and twenty-eight, that is, its life expectancy was about nine hundred and nineteen years. This record is documented as the longest life of a tree in Russia.

Since in Yakutia many long-lived trees grow in one area, scientists propose giving this forest area the status of a protected area.

The oldest tree in Moscow

It is believed that the oldest trees in the capital grow in Kolomensky Park; these are oaks, whose age is approximately equal to the age of Moscow itself. A tree of the same age grows in Kuskovsky Park. This is a veteran oak. All these oak trees are estimated to be between four hundred and six hundred years old. According to some scientists, in Kolomensky Park there are oak trees whose age has exceeded a thousand years.

One of the oldest Moscow trees is considered to be a three-hundred-year-old willow, growing in the botanical garden of Moscow State University "Apothecary Garden". This Botanical Garden- the oldest in Russia.

Where are there a lot of old trees?

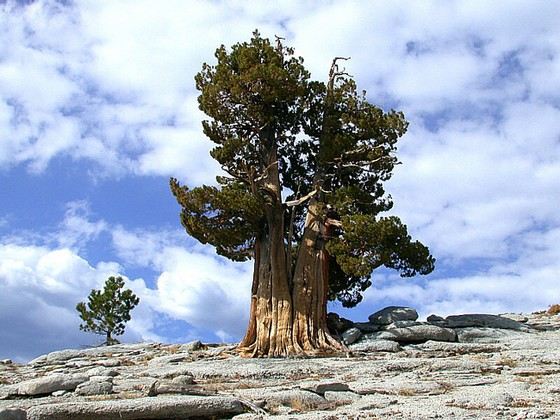

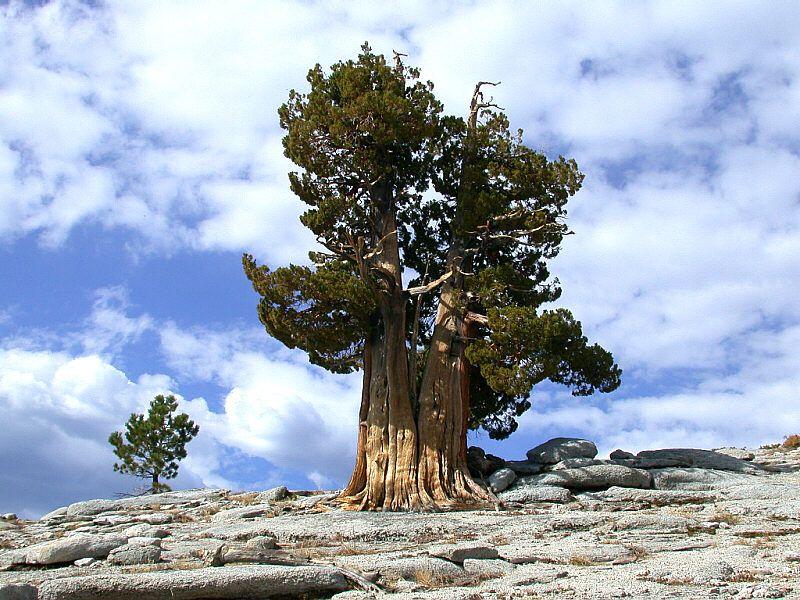

There are places on earth where many old trees grow. One such place is Mount Fulu in Sweden. Scientists, taking a census of trees, accidentally discovered pine trees there that are several thousand years old. There is a pine tree growing there, which is supposedly about ten thousand years old. It’s surprising that several other record-breaking pines grow next to it.

In America, in the state of Utah, there is a colony of poplars, which are supposed to be at least eighty thousand years old. The fact is that poplars do not live long, but a poplar colony exists as a single organism with a common root system, producing new shoots from time to time. It turns out that all poplars today are clones of a single tree.

The neighbors of the elder among the trees of Methuselah are trees that could well have witnessed the beginning of our era. There is a park in the USA where there are several cypress trees that are at least three and a half thousand years old - this is Big Tree Park. Many long-lived redwoods can be found in California national park. There also grows a tree whose name is “General Shermann,” which is the tallest and at the same time one of the oldest on the planet.

It is quite possible that people will discover many new oldest trees. After all, many of them grow in remote corners, where people rarely set foot, and where they can only be found by chance. By the way, sequoias, according to the site, are also the largest plants in the world. They easily grow over 100 meters in height. True, this requires more than a dozen years.

The world's oldest tree

California's Inyo National Forest is home to the oldest tree on the planet, four thousand eight hundred and forty-two years old. He was given the name "Methuselah". This is an intermountain bristlecone pine. Judging by its age, the tree grew when none of the pyramids had yet been built in Egypt.

This tree was discovered by one of the botanists in the mid-twentieth century. For five years, scientists studied this pine, after which a message about Methuselah appeared in National Geographic. To protect the tree, information about its exact location is not disclosed. This is done to avoid vandalism. Several teams of scientists claim that it is not Methuselah who is long-lived, but a pine tree growing in Sweden, whose age is about ten thousand years.

If you find yourself in some of the oldest trees on the planet on your upcoming summer trip, you can visit them for a great experience.

1. In the “Forest of Ancient Long-Lasting Pines,” or Inyo National Forest, in eastern California, grows the oldest free-standing tree on Earth - Methuselah. According to rough estimates, its age is more than 4800 years. It’s hard to even imagine that it was already growing before the first pyramid appeared in Egypt! Visitors to the Inyo National Forest can view the relict pines that grow in abundance in this forest of ancient pines, but the exact location of Methuselah is not disclosed due to fear of vandalism. Therefore, many tourists only have to guess which pine tree is the oldest on the planet out of hundreds of bizarre pines growing in the forest.

2., California. National Park Sequoia. A giant one grows here. This is not only the oldest sequoia on Earth, but also the tallest of its fellows. Its height is 84 meters, and its girth at the base is 31 meters. The approximate age of this giant is 2300-2700 years. Next to this gigantic living creature, a person seems so small and fragile! No wonder the General Sherman sequoia attracts many tourists. They describe the tree as "a huge red-orange rock, the tops of which cannot be seen." Surprisingly, this tree is still growing, adding approximately 1.5 centimeters in girth every year. Near the tree, the Americans, who love to translate everything into numbers, indicated on a sign that 40 houses could be built from sequoia wood, and if it were placed next to by passenger train, then it would be much longer. But it’s not a matter of a large volume of wood! When tourists are told that the tree grew before King Tutankhamun, it takes their breath away.

3. (plane tree), native to Nagorno-Karabakh, is approximately 2000 years old. The height of this giant is 54 meters, and the trunk circumference is about 27 meters. At the base of the tree there is a huge hollow with an area of about 44 square meters, which can easily accommodate about a hundred people. The size of plane tree leaves reaches half a meter. It is interesting that this tree is clearly visible from space, because the crown of the plane tree has an area of about one and a half thousand square meters. Local population reveres this tree as a shrine, because, according to legend, the most prominent people of these places sat in the shade of the plane tree.

4. In Sant'Alfio, on the slopes of Mount Etna in (Italy), the world's oldest chestnut grows, which is known as "The Tree of a Hundred Horses" . According to legend, the Queen of Aragon and a hundred knights accompanying her took refuge from the rain under the crown of this chestnut tree. This tree is the most voluminous on Earth, because the girth of its trunk is about 58 meters. The age of the chestnut is unknown; scientists offer different figures - from 2000 to 4000 years. In general, it’s amazing how this relict tree could survive just 8 km from the vent active volcano Etna.

5. Sarv-e Abar-Kuh , or . This tree grows in Iran, in the province of Yazd. This majestic cypress is perhaps the oldest living creature in Asia, its age is 4-4.5 thousand years. Around the same time, the wheel was invented by Asian artisans. It’s amazing how much time has passed since how far human civilization has advanced, and tired travelers can still rest in the shade of this tree! The height of the tree is 25 meters, 18 meters in girth. The tree is a national monument and one of the main attractions.

6. in north Wales is located on the territory of a small church. The approximate age of the tree is 4000 years. Despite its advanced age, the tree still continues to grow. In 2002, in honor of Queen Elizabeth II's Jubilee, the yew was included in the list of the 50 Great Trees of Great Britain. There are many legends and stories about the tree. One of them says that under the yew tree lives evil spirit, who on Halloween in a creepy voice calls out the names of those villagers who are expected to die this year. Those who don't believe this can go to the village on Halloween and check the truth of the legend. All conditions have been created for tourists.

7. The most old spruce grows on Mount Fulufjallet in Sweden. She also has a name, called . This spruce, it’s hard to even imagine, is more than 9,500 years old. The age of the spruce was determined by radiocarbon dating of the root system. Moreover, the current trunk of Tikko is not very remarkable, it is only a few hundred years old and the tree is no more than 5 meters high. Apparently, the old tree died, but the surviving roots gave rise to new growth. Therefore, this spruce is a true clone tree. It grew not from a seed, but from an ancient rhizome. The roots of this ancient spruce remember those times about which we know very little.

Most of our forests are young. They are between a quarter and a third of their lives. Apparently, in the 19th century certain events occurred that led to the almost total destruction of our forests. Our forests keep big secrets...

It was a wary attitude towards Alexei Kungurov’s statements about Perm forests and clearings at one of his conferences that prompted me to conduct this research. Well, of course! There was a mysterious hint of hundreds of kilometers of clearings in the forests and their age. I personally was hooked by the fact that I walk through the forest quite often and quite far, but I didn’t notice anything unusual.

And this time the amazing feeling was repeated - the more you understand, the more new questions appear. I had to re-read a lot of sources, from materials on forestry of the 19th century to the modern “Instructions for carrying out forest management in the forest fund of Russia.” This did not add clarity, rather the opposite. But there was a certainty that something was fishy here.

The first surprising fact that was confirmed is the size of the quarterly network. A quarter network, by definition, is “a system of forest quarters created on forest fund lands for the purpose of inventorying the forest fund, organizing and maintaining forestry and forest management.”

The quarterly network consists of quarterly clearings. This is a straight strip cleared of trees and shrubs (usually up to 4 m wide), laid in the forest to mark the boundaries of forest blocks. During forest management, quarterly clearings are cut and cleared to a width of 0.5 m, and their expansion to 4 m is carried out in subsequent years by forestry workers.

For example, in the forests of Udmurtia, blocks have a rectangular shape, the width of 1 block is 1067 meters, or exactly 1 mile. Until that moment, I was firmly convinced that all these forest roads were the work of Soviet foresters. But why the hell did they need to mark out the quarterly network in miles?

I checked. The instructions state that blocks should be 1 by 2 km in size. The error at this distance is allowed no more than 20 meters. But 20 is not 340. However, all forest management documents stipulate that if block network projects already exist, then you should simply link to them. This is understandable; the work of laying clearings is a lot of work to redo.

Today there are already machines for cutting down glades, but we should forget about them, since almost the entire forest fund of the European part of Russia, plus part of the forest beyond the Urals, approximately to Tyumen, is divided into a mile-long block network. There are also kilometer-long ones, of course, because in the last century foresters have also been doing something, but mostly it’s the mile-long one. In particular, in Udmurtia there are no kilometer-long clearings. This means that the design and practical construction of a block network in most of the forested areas of the European part of Russia were made no later than 1918. It was at this time that the metric system of measures was adopted for mandatory use in Russia, and the mile gave way to the kilometer.

It turns out that it was done with axes and jigsaws, if we, of course, correctly understand historical reality. Considering that the forest area of the European part of Russia is about 200 million hectares, this is a titanic task. Calculations show that the total length of the clearings is about 3 million km. For clarity, imagine the first lumberjack, armed with a saw or an ax. In a day he will be able to clear on average no more than 10 meters of clearing. But we must not forget that this work can be carried out mainly in winter. This means that even 20,000 lumberjacks, working annually, would create our excellent verst quarter network for at least 80 years.

But there has never been such a number of workers involved in forest management. Based on materials from articles of the 19th century, it is clear that there were always very few forestry specialists, and the funds allocated for these purposes could not cover such expenses. Even if we imagine that for this purpose peasants were driven from surrounding villages to do free work, it is still unclear who did this in the sparsely populated areas of the Perm, Kirov, and Vologda regions.

After this fact, it is no longer so surprising that the entire neighborhood network is tilted by about 10 degrees and is directed not to the geographic north pole, but, apparently, to the magnetic one (the markings were carried out using a compass, not a GPS navigator), which should have been in this time to be located approximately 1000 kilometers towards Kamchatka. And it’s not so confusing that the magnetic pole, according to official data from scientists, has never been there from the 17th century to the present day. It’s no longer scary that even today the compass needle points in approximately the same direction in which the quarterly network was made before 1918. All this cannot happen anyway! All logic falls apart.

But it is there. And in order to finish off the consciousness clinging to reality, I inform you that all this equipment also needs to be serviced. According to the norms, a complete audit takes place every 20 years. If it passes at all. And during this period of time, the “forest user” must monitor the clearings. Well, if anyone was watching in Soviet times, it’s unlikely that over the past 20 years. But the clearings were not overgrown. There is a windbreak, but there are no trees in the middle of the road. But in 20 years, a pine seed that accidentally fell to the ground, of which billions are sown annually, grows up to 8 meters in height. Not only are the clearings not overgrown, you won’t even see stumps from periodic clearings. This is all the more striking in comparison with power lines, which special teams regularly clear of overgrown bushes and trees.

This is what typical clearings in our forests look like. Grass, sometimes there are bushes, but no trees. There are no signs of regular maintenance.

The second big mystery is the age of our forest, or the trees in this forest. In general, let's go in order.

First, let's figure out how long a tree lives. Here is the corresponding table.

* in brackets - height and life expectancy in particularly favorable conditions.

In different sources, the figures differ slightly, but not significantly. Pine and spruce should live up to 300...400 years under normal conditions. You begin to understand how absurd everything is only when you compare the diameter of such a tree with what we see in our forests. A 300-year-old spruce should have a trunk with a diameter of about 2 meters. Well, like in a fairy tale. The question arises: Where are all these giants? No matter how much I walk through the forest, I haven’t seen anything thicker than 80 cm. There aren’t many of them. There are individual specimens (in Udmurtia - 2 pines) that reach 1.2 m, but their age is also no more than 200 years.

Wheeler Peak (4,011 m above sea level), New Mexico, is home to bristlecone pines, one of the longest-lived trees on Earth. The age of the oldest specimens is estimated at 4,700 years.

In general, how does the forest live? Why do trees grow or die in it?

It turns out that there is a concept of “natural forest”. This is a forest that lives its own life - it has not been cut down. It has a distinctive feature - low crown density from 10 to 40%. That is, some trees were already old and tall, but some of them fell affected by fungus or died, losing competition with their neighbors for water, soil and light. Large gaps form in the forest canopy. A lot of light begins to get there, which is very important in the forest struggle for existence, and young animals begin to actively grow. Therefore, a natural forest consists of different generations, and crown density is the main indicator of this.

But if the forest was clear-cut, then new trees grow simultaneously for a long time, the crown density is high, more than 40%. Several centuries will pass, and if the forest is not touched, then the struggle for a place in the sun will do its job. It will become natural again. Do you want to know how much natural forest there is in our country that is not affected by anything?

Look at the map of Russian forests.

Bright shades indicate forests with a high canopy density, that is, these are not “natural forests.” And these are the majority. The entire European part is indicated in rich blue. This is, as indicated in the table: “Small-leaved and mixed forests. Forests with a predominance of birch, aspen, gray alder, often with an admixture of coniferous trees or with separate areas of coniferous forests. Almost all of them are derivative forests, formed on the site of primary forests as a result of logging, clearing, and forest fires.”

You don’t have to stop at the mountains and tundra zone; there the rarity of crowns may be due to other reasons. But the plains and middle zone are clearly covered with young forest. How young? Go and check it out. It is unlikely that you will find a tree in the forest that is older than 150 years. Even a standard drill for determining the age of a tree is 36 cm long and is designed for a tree age of 130 years. How does forest science explain this? Here's what they came up with:

“Forest fires are a fairly common phenomenon for most of the taiga zone of European Russia. Moreover: forest fires in the taiga are so common that some researchers consider the taiga as many burnt areas of different ages - more precisely, many forests formed on these burnt areas. Many researchers believe that forest fires are, if not the only, then at least the main natural mechanism for forest renewal, replacing old generations of trees with young ones..."

All this is called “dynamics of random violations.” That's where the dog is buried. The forest was burning, and burning almost everywhere. And this, according to experts, is the main reason for the low age of our forests. Not fungus, not bugs, not hurricanes. Our entire taiga is in burnt areas, and after a fire, what remains is the same as after clear cutting. Hence the high crown density throughout almost the entire forest zone. Of course, there are exceptions - truly untouched forests in the Angara region, on Valaam and, probably, somewhere else in the vast expanses of our vast Motherland. There are really fabulously large trees there in their mass. And although these are small islands in the vast sea of taiga, they prove that a forest can be like that.

What is so common about forest fires that over the past 150...200 years they have burned the entire forest area of 700 million hectares? Moreover, according to scientists, in a certain checkerboard order, observing the order, and certainly at different times?

First we need to understand the scale of these events in space and time. The fact that the main age of old trees in the bulk of forests is at least 100 years old suggests that the large-scale burns that so rejuvenated our forests occurred over a period of no more than 100 years. Translating into dates, for the 19th century alone. To do this, it was necessary to burn 7 million hectares of forest annually.

Even as a result of large-scale forest arson in the summer of 2010, which all experts called catastrophic in volume, only 2 million hectares burned. It turns out there is nothing “so ordinary” about this. The last justification for such a burned-out past of our forests could be the tradition of slash-and-burn agriculture. But how, in this case, can we explain the state of the forest in places where traditionally agriculture was not developed? In particular, in the Perm region? Moreover, this method of farming involves labor-intensive cultural use of limited areas of forest, and not at all the uncontrolled burning of large tracts in the hot summer season, and with the wind.

Having gone through all the possible options, we can say with confidence that the scientific concept of “dynamics of random disturbances” is not substantiated by anything in real life, and is a myth intended to mask the inadequate state of the current forests of Russia, and therefore the events that led to this.

We will have to admit that our forests either burned intensely (beyond any norm) and constantly throughout the 19th century (which in itself is inexplicable and not recorded anywhere), or burned at once as a result of some incident, which is why the scientific world furiously denies having no arguments, except that nothing of the kind is recorded in official history.

To all this we can add that there were clearly fabulously large trees in old natural forests. It has already been said about the preserved areas of the taiga. It is worth giving an example regarding deciduous forests. The Nizhny Novgorod region and Chuvashia have a very favorable climate for deciduous trees. There are a huge number of oak trees growing there. But, again, you won’t find old copies. The same 150 years, no older. Older single copies are all the same. Here is a photo of the largest oak tree in Belarus. It grows in Belovezhskaya Pushcha. Its diameter is about 2 meters, and its age is estimated at 800 years, which, of course, is very arbitrary. Who knows, maybe he somehow survived the fires, this happens. The largest oak tree in Russia is considered to be a specimen growing in the Lipetsk region. According to conventional estimates, he is 430 years old.

A special theme is bog oak. This is the one that is extracted mainly from the bottom of rivers. My relatives from Chuvashia told me that they pulled out huge specimens up to 1.5 m in diameter from the bottom. And there were many of them. This indicates the composition of the former oak forest, the remains of which lie at the bottom. In the Gomel region there is a river Besed, the bottom of which is dotted with bog oak, although now there are only water meadows and fields all around. This means that nothing prevents current oak trees from growing to such sizes. Did the “dynamics of random disturbances” in the form of thunderstorms and lightning work in some special way before? No, everything was the same. So it turns out that the current forest simply has not yet reached maturity.

Let's summarize what we learned from this study. There are a lot of contradictions between the reality that we see with our own eyes and the official interpretation of the relatively recent past:

There is a developed block network over a vast area, which was designed in versts and was laid no later than 1918. The length of the clearings is such that 20,000 lumberjacks, using manual labor, would take 80 years to create it. The clearings are maintained very irregularly, if at all, but they do not become overgrown.

On the other hand, according to historians and surviving articles on forestry, there was no funding of comparable scale and the required number of forestry specialists at that time. There was no way to recruit such a quantity of free labor. There was no mechanization to facilitate this work.

We need to choose: either our eyes deceive us, or the 19th century was not at all what historians tell us. In particular, there could be mechanization commensurate with the tasks described.

There could also have been less labor-intensive, effective technologies for laying and maintaining clearings, which have been lost today (some distant analogue of herbicides). It is probably stupid to say that Russia has not lost anything since 1917. Finally, it is possible that clearings were not cut, but trees were planted in blocks in areas destroyed by fire. This is not such nonsense compared to what science tells us. Although doubtful, it at least explains a lot.

Our forests are much younger than the natural lifespan of the trees themselves. This is evidenced by the official map of Russian forests and our eyes. The age of the forest is about 150 years, although pine and spruce under normal conditions grow up to 400 years and reach 2 meters in thickness. There are also separate areas of forest with trees of similar age.

According to experts, all our forests are burnt. It is fires, in their opinion, that do not give trees a chance to live to their natural age. Experts do not even allow the thought of the simultaneous destruction of vast expanses of forest, believing that such an event could not go unnoticed. In order to justify this ashes, official science adopted the theory of “dynamics of random disturbances.” This theory proposes that forest fires are considered a common occurrence, destroying (according to some incomprehensible schedule) up to 7 million hectares of forest per year, although in 2010 even 2 million hectares destroyed as a result of deliberate forest fires were called a disaster.

We need to choose: either our eyes are deceiving us again, or some grandiose events of the 19th century with particular impudence were not reflected in the official version of our past, just as neither the Great Tartary nor the Great Northern Route fit into it. Atlantis and the fallen moon didn’t even fit. The simultaneous destruction of 200...400 million hectares of forest is even easier to imagine and hide than the undying, 100-year fire proposed for consideration by science.

So what is the age-old sadness of Belovezhskaya Pushcha about? Is it not about those severe wounds of the earth that the young forest covers? After all, giant fires don’t happen on their own...

basis: article by A. Artemyev

How old are the trees in Russia or where from 200 years

I was just present at Alexei Kungurov’s Internet conference when he first announced this number 200, but the meaning of the statement was that in Russia there are no trees OLDER than 200 years old.

The Internet does not provide the average statistical age of trees growing in Russia, but according to indirect data, the date of 150 years is still the most accurate.

In his article, “In Russia, are there almost no trees older than 200 years?”, to which there are many links on the Internet, the author of the article, Alexey Artemyev, says that the plains and middle zone are covered by “obviously young forest. It is unlikely that you will find a tree in the forest that is older than 150 years. Even a standard drill for determining the age of a tree is 36 cm long and is designed for a tree age of 130 years.”

Average age trees of Russia

There is an official map of Russian forests, and according to it, the age of the forest is also about 150 years.

From the advertising brochure: “On the border of Moscow, Kaluga and Tula regions The Velegozh Sanatorium (Resort) is located. It is only 114 km from Moscow and 84 km from Tula. The territory of the sanatorium is located in pine forest, on the high bank of the Oka River. The average age of trees is 115-120 years.”

There is such a famous Kazan (Volga region) Federal University.

Here are the graphs from the training manual for the course dendroecology (Methods of tree-ring analysis):

Please note that the starting dates of the charts are 1860.

But here is what is said in the work of A.V. Kuzmina, O.A. Goncharova:

"PABSI KSC RAS, Apatity, RF CLASSIFICATION AND TYPIZATION OF PINE STAND ELEMENTS BASED ON ANALYSIS OF THE PROBABILITY DENSITY DISTRIBUTION OF SIZE CLASSES OF RADIAL INCREMENTS

"Forest communities on Kola Peninsula are at the northern limit of distribution. total area taiga zones within the peninsula 98 thousand km2

Research was carried out on the territory Murmansk region near the village of Alakurtti (Kola Peninsula). The region's territory is located between 66o03′ and 69o57′ N latitudes. and 28o25′ and 41o26′ E. Most of the territory is located outside the Arctic Circle.

The purpose of the study is to develop a classification of plants by productivity based on an analysis of the distribution of absolute indicators of annual radial growth.

A compact forest stand consisting of 30 pines with no signs of anthropogenic impact was chosen as a model object.

forest communities on the Kola Peninsula, 150 years old, average age of trees in Russia Using a Pressler drill, core samples were taken from each pine tree, drilling was carried out to the core. The study of cores for the number of annual layers was carried out automated system telemetric analysis of wood cores (Kuzmin A.V. et al., 1989).

Average age of plants in the selected model area: - 146 years

Based on the similarity of rows, trees are differentiated into groups,

Group B includes 15 trees (50% of the total) - the average age of pines in group B is 150 years.

Group B includes 8 trees (27% of the total) - the average age of pines in group B is 146 years.

Group G includes 4 trees of the 6th, 8th and 9th age classes - the average age of pines in group G is 148 years

In total, each selected group contains plants of almost all age classes. The average age of the intermediate groups B, C and D is close to: 150, 146 and 148 years.”

So, where the forests went 150 years ago is unknown, but it is quite possible that they were destroyed. Probably not only forests. But this will be even worse.

But the entire chronology of Oleg and Alexandra falls exactly on this date of 150 years. For which we are very grateful to them. By the way, Alexey Kungurov presented many photos in his conferences confirming that there were craters all over the planet.

The forest communities of the Kola Peninsula are the most northern in the European part of Russia as they are located on the border of the northern limit of distribution. The entire area of the peninsula is divided into the forest-tundra subzone (46 thousand km2) and the northern taiga subzone (52 thousand km2) (Zaitseva I.V. et al., 2002).

The selected model tree stand is continental forest in nature.

The experimental area is characterized by the following parameters:

Soil moisture is average.

- The relief of the area is flat,

- Composition of the forest stand: 10C.

- Type of forests: lichen-lingonberry.

- Undergrowth: birch, willow.

- Undergrowth: spruce is rare in groups, pine is abundant in groups.

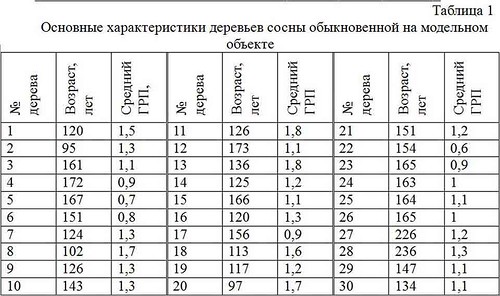

The characteristics of the examined Scots pine plants are summarized in Table 1:

The surveyed trees are divided into six age classes (grades 5-9, 12). No plants of the 10th and 11th age classes were found in the surveyed area. The most widespread (9 specimens) is class 9, which includes trees 161-180 years old. The smallest numbers are 5th and 12th age classes (2 trees each), i.e. The youngest and oldest plants are poorly represented in the surveyed area. The 6th, 7th and 8th age classes contain 5, 6 and 6 trees, respectively. Average age class - 8 ± 0.3.

Previously, it was believed that on the Kola Peninsula, in woody plants, the distribution of timing of the passage of phenological phases is subject to the law of normal distribution. (O.A. Goncharova, A.V. Kuzmin, E.Yu. Poloskova, 2007)

In order to analyze the distribution of probability density values of annual radial increments (ARI) in the studied 30 specimens of Scots pine, the empirical RPV of the AGR was checked. The calculated RPV of hydraulic fracturing in most cases does not correspond to the laws of normal distribution. Classes from 5 to 9 contain one tree each, the RPV of which corresponds to normal indicators; in age class 12, such data have not been established.

Analysis of the distribution of GRP values relative to the average values for each individual showed that in most plants, GRP values below the average value predominate. In trees 1, 9, 11, 16, the ratio of hydraulic fracturing values below or above the average is approximately the same, with a slight predominance towards lower values. In pine 12, the ratio of hydraulic fracturing values is similar below or above average, approximately the same, but with a slight predominance towards higher values. The dominance of large hydraulic fracturing values has not been established relative to the average value.

The next step was to classify the surveyed set of trees according to productivity based on the distribution of absolute values of annual radial growth. The contingency system of probability density distributions of hydraulic fracturing values was analyzed using the nonparametric Spearman correlation coefficient. Further work took into account only reliable correlation coefficients (G.N. Zaitsev, 1990). Positive conjugate connections were revealed.

The trees are differentiated into groups based on the similarity of the series of probability density distributions based on the number of identified correlations.

Group A includes tree 25, this pine belongs to age class 9, its age is above average, within the boundaries of the age class it is correlated with all trees. This tree has a maximum number of correlations with neighboring plants (27); there is no correlation with plants 2 and 19, which have a minimum of correlations. The specified tree is defined as a standard for the considered set of trees.

Group B includes 15 trees (50% of the total). Representatives of this group have correlation connections from 23 to 26. Group B contains trees of all identified age classes, except for the youngest (class 5). The average age of trees in group B is 150 years. Plants of the 7th and 8th age classes are most fully represented in the category.

8 trees (27% of the total) were separated into group B. Each tree has from 18 to 21 conjugated links. Here, age class 9 (5 trees) is most represented, single specimens are age classes 5, 6, 7 (1 plant each). The average age of trees in group B is 146 years.

Group D includes 4 plants of age classes 6, 8 and 9. Trees in this part of the studied forest stand are characterized by 12-15 conjugated connections. The average age of trees in group G is 148 years.

Instances included in group D are distinguished by a minimum of correlations with other representatives - conjugate connections 7 and 3, respectively, these are trees 2 and 19. These trees are representatives of age classes 5 and 6, that is, the youngest classes.

In total, each selected group includes trees of almost all age classes. The average age of groups B, C and D, which took an intermediate position, is close to: 150, 146 and 148 years. So the age of Russian trees is not 200 years, but much less...

Alexander Galakhov.

And finally: our planet is becoming overgrown with forests. Moreover, this phenomenon is quite recent. Examples with photos:

An interesting excerpt from Alexey Kungurov's answer