Sculpture from ancient Greece. Sculpture of the classical era: beauty without whimsicality and wisdom without effeminacy

The image of an athlete is still the most common theme in sculpture. Perfect human beauty is what the Greeks sought to embody in the images of athletes. Figure of a Delphic charioteer from a composition created around 476 BC. e. by an unknown master. The figure is cast in bronze, which has since become a favorite material.

Not only anonymous works of the 5th century are known. BC e. At this time, the sculptures of Phidias, Myron and Polykleitos were working in Athens. Many of their statues have come down to us only in Roman marble copies of the 1st-2nd centuries. n. e. The most famous among the works of Myron from Eleuthera is the “Disco Thrower” (circa 460-450 BC), depicting an athlete at the moment of highest tension before throwing a discus. Myron was the first to convey in static art the liveliness of movement and the internal tension of a figure. In another work, “Athena and Marsyas,” performed for the Athenian acropolis, the forest creature Marsyas selects a musical instrument from among those scattered at his feet, and Athena stands nearby, looking at him with anger. Both figures are united by action. It is interesting to note that, although Marsyas appears here as a negative being, in modern language, only his irregular face emphasizes the lack of perfection, while his body is ideally beautiful.

Polykleitos from Argos worked already during the high classic period, in the middle and second half of the 5th century. BC e. He created that generalized artistic image of an athlete, which became the norm and model. He wrote a theoretical treatise “Canon” (measure, rule), where the sculptor accurately calculated the sizes of body parts based on human height as a unit of measurement (for example, head - 1/7 of height, face and hand - 1/10, foot - 1/6, etc.). He expressed his ideal in the restrained, powerful, calmly majestic images of “Doriphoros” (Spearman; 450-440 BC), “Diadumen” (an athlete crowning his head with a victorious bandage, around 420 BC). BC) and the “Wounded Amazon”, intended for the famous Temple of Artemis in Ephesus. Polykleitos embodied in his statues, first of all, the image of an ideal free-born citizen of the polis, the city-state of Athens.

The third greatest sculptor of the 5th century. BC e. was the already mentioned Athenian Phidias. In 480-479 The Persians captured and plundered Athens and the main sanctuaries on the Acropolis. Among the ruins of the sacred temple, Phidias created a seven-meter bronze statue of Athena the warrior, Athena-Promachos, with a spear and shield in her hands, as a symbol of the revival of the city, its power and intransigence towards enemies. Like all subsequent works of Phidias, the statue perished (it was destroyed by the crusaders in Constantinople in the 13th century).

Around 448 BC. Phidias made a 13-meter statue of Zeus for the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The face, hands and body of the god were lined with ivory plates on a wooden base, the eyes were made of precious stones, the cloak, sandals, olive branches on the head, hair, and beard were made of gold (the so-called chrysoelephantine technique). Zeus sat on the throne, holding in his hands a scepter and the figure of the goddess of victory. The sculpture enjoyed enormous fame, but it also died in the 5th century. n. e.

From 449 BC e. The reconstruction of the Athenian Acropolis began and Phidias became the embodiment of Pericles' plan, supported by all Athenians.

In sculpture, the masculinity and severity of the images of strict classics is replaced by an interest in the spiritual world of man, and a more complex and less straightforward characteristic of it is reflected in plastic. Thus, in the only marble statue of Hermes that has come down to us in the original by the sculptor Praxiteles (circa 330 BC), the master depicted a beautiful young man casually leaning on a stump, in a state of peace and serenity. He looks thoughtfully and tenderly at the baby Dionysus, whom he holds in his arms. To replace the manly beauty of the 5th century athlete. BC e. a beauty comes that is somewhat feminine, graceful, but also more spiritual. The statue of Hermes retains traces of ancient coloring: red-brown hair, a silver bandage. Another sculpture of Praxiteles, the statue of Aphrodite of Knidos, enjoyed particular fame. This was the first depiction of a nude female figure in Greek art. The statue stood on the shore of the Knidos peninsula, and contemporaries wrote about real pilgrimages here to admire the beauty of the goddess preparing to enter the water and throwing off her clothes on a nearby vase. Unfortunately, the original statue of Aphrodite of Knidos has not survived. The heroes of Praxiteles are not alien to a lyrical feeling, clearly expressed, for example, in his “Resting Satire”. Similar features developed even earlier, in the plastic arts of students of the Phidias school; it is enough to point out “Aphrodite in the Gardens” by Alkamen, the reliefs of the balustrade of the temple of Nike Apteros or the tombstone of Hegeso by unknown masters.

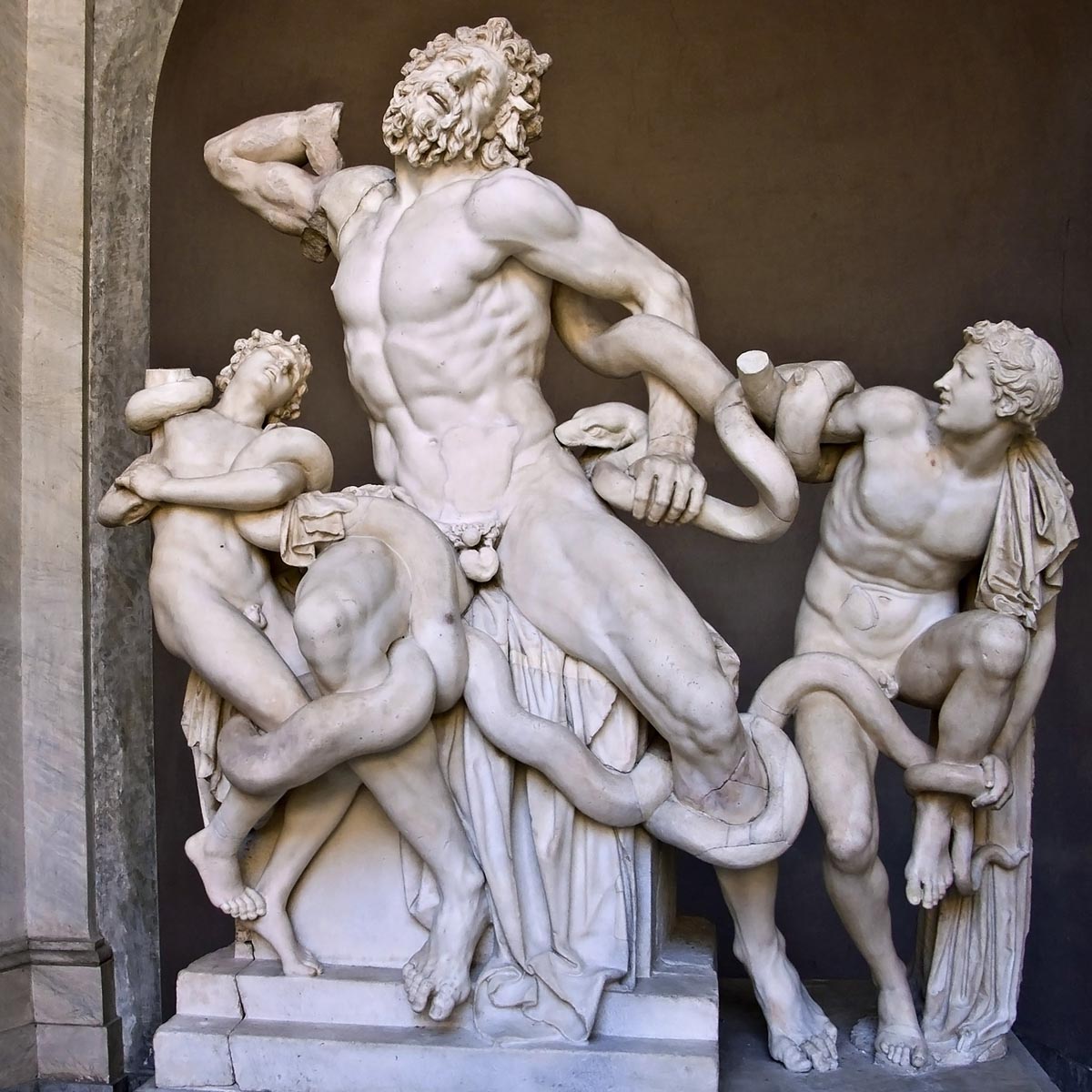

Skopas, a native of the island of Paros, was a contemporary of Praxiteles. He participated in the creation of a relief frieze for the Halicarnassus mausoleum together with Timothy, Leochares and Briaxis. Unlike Praxiteles, Skopas continued the traditions of high classics, creating monumental heroic images. But from the images of the 5th century. they are distinguished by the dramatic tension of all spiritual forces.

In a state of ecstasy, in a violent outburst of passion, the Maenad is depicted by Scopas. The companion of the god Dionysus is shown in a rapid dance, her head is thrown back, her hair has fallen to her shoulders, her body is curved, presented in a complex angle, the folds of her short chiton emphasize the violent movement. The play of chiaroscuro enhances the dynamics of the image.

Unlike the sculpture of the 5th century. The Skopas maenad is designed to be viewed from all sides.

Lysippos - the third great sculptor of the 4th century. BC e. (370-300 BC). He worked in bronze and, according to ancient writers, left behind 1,500 bronze statues, which have not reached us in the original. Lysippos used already known plots and images, but sought to make them more lifelike, not ideally perfect, but characteristically expressive. Thus, he showed athletes not at the moment of the highest tension of strength, but, as a rule, at the moment of their decline, after the competition. This is exactly how his Apoxyomenos is represented, cleaning off the sand from himself after a sports fight. He has a tired face and his hair is matted with sweat. The captivating Hermes, always fast and lively, is also represented by Lysippos as if in a state of extreme fatigue, briefly sitting on a stone and ready to run further in the next second in his winged sandals. Lysippos and Hercules are depicted tired from their labors (“Hercules Resting”). Lysippos created his own canon of proportions of the human body, according to which his figures are taller and slimmer than those of Polykleitos (the size of the head is 1/9 of the figure).

Lysippos was a multifaceted artist. The court sculptor of Alexander the Great, he made giant multi-figure compositions, for example, a battle of 25 figures of horsemen, statues of gods, portraits (more than once he depicted Alexander the Great; the best of the portraits of the famous commander bears the features of almost tragic confusion).

For art late classic It was characterized by the introduction of new genres, which found further development at the next stage - in Hellenism.

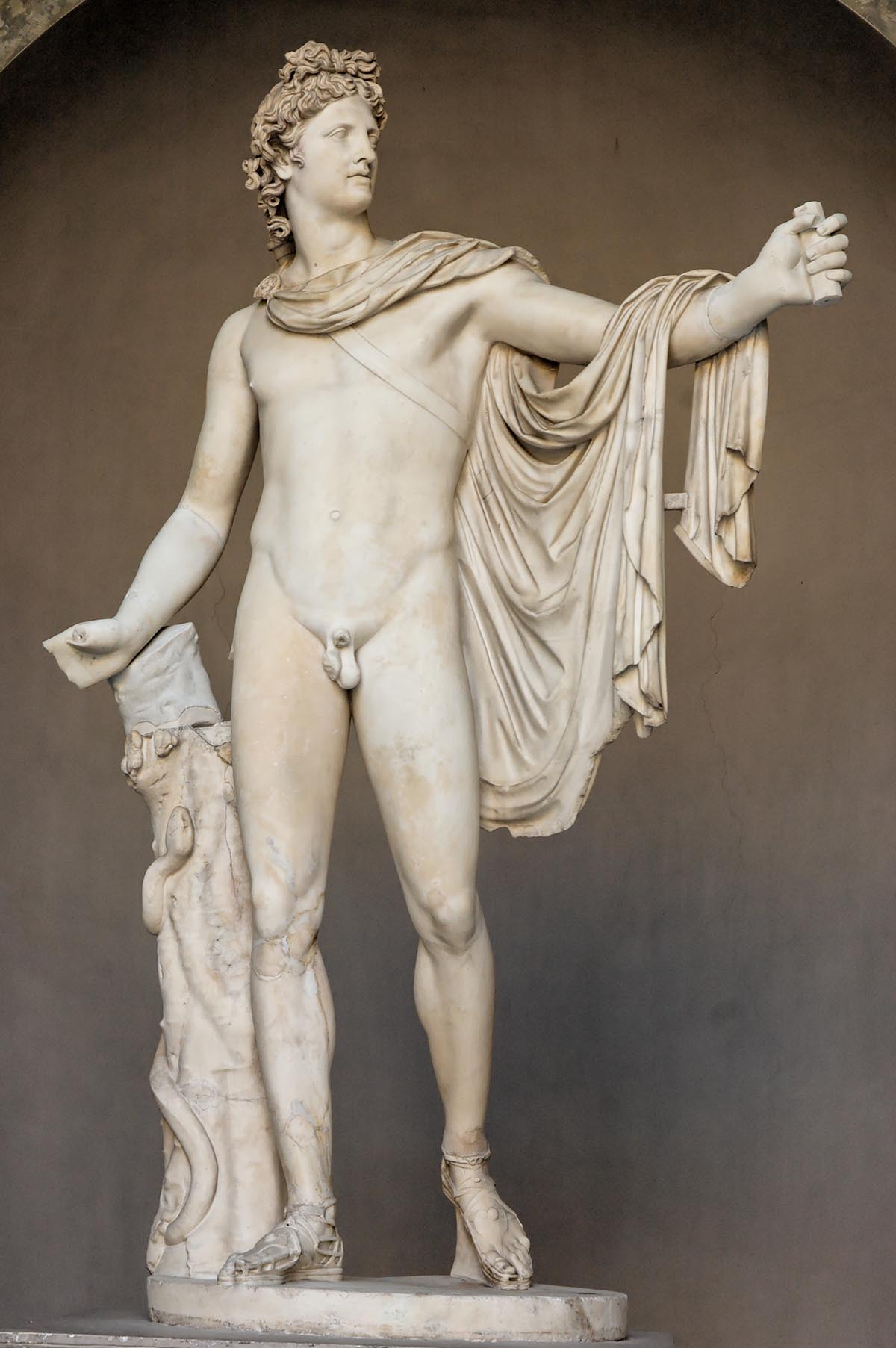

The classical period of ancient Greek sculpture falls on the V - IV centuries BC. (early classic or “strict style” - 500/490 - 460/450 BC; high - 450 - 430/420 BC; “rich style” - 420 - 400/390 BC; Late Classic -- 400/390 - OK. 320 BC e.). At the turn of two eras - archaic and classical - stands the sculptural decor of the Temple of Athena Aphaia on the island of Aegina . The sculptures of the western pediment date back to the founding of the temple (510 - 500 BC BC), sculptures of the second eastern, replacing the previous ones, - to the early classical time (490 - 480 BC). The central monument of ancient Greek sculpture of the early classics is the pediments and metopes of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (about 468 - 456 BC e.). Another significant work of the early classics -- the so-called “Throne of Ludovisi”, decorated with reliefs. A number of bronze originals have also survived from this time - “The Delphic Charioteer”, statue of Poseidon from Cape Artemisium, Bronze from Riace . The largest sculptors of the early classics - Pythagoras Regian, Kalamid and Miron . We judge the work of famous Greek sculptors mainly from literary evidence and later copies of their works. High classicism is represented by the names of Phidias and Polykleitos . Its short-term heyday was associated with work at Athens Acropolis, that is, with the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon (Pediments, metopes and zophoros survived, 447 - 432 BC). The pinnacle of ancient Greek sculpture was, apparently, chrysoelephantine Athena Parthenos statues and Zeus of Olympus by Phidias (both have not survived). “Rich style” is characteristic of the works of Callimachus, Alcamenes, Agorakrit and other sculptors of the 5th century. BC e.. Its characteristic monuments are the reliefs of the balustrade of the small temple of Nike Apteros on the Athenian Acropolis (about 410 BC) and a number of funerary steles, among which the most famous is the Hegeso stele . The most important works of ancient Greek sculpture of the late classics - the decoration of the Temple of Asclepius in Epidaurus (about 400 - 375 BC), temple of Athena Aley in Tegea (about 370 - 350 BC), the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus (about 355 - 330 BC) and the Mausoleum in Halicarnassus (c. 350 BC), on the sculptural decoration of which Scopas, Briaxides, Timothy worked and Leohar . The latter is also credited with the statues of Apollo Belvedere and Diana of Versailles . There are also a number of bronze originals from the 4th century. BC e. The largest sculptors of the late classics - Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos, in many ways anticipating the subsequent era of Hellenism.

Greek sculpture partially survived in rubble and fragments. Most of the statues are known to us from Roman copies, which were made in large numbers, but did not convey the beauty of the originals. Roman copyists roughened and dried them, and when converting bronze items into marble, they disfigured them with clumsy supports. The large figures of Athena, Aphrodite, Hermes, Satyr, which we now see in the halls of the Hermitage, are only pale rehashes of Greek masterpieces. You walk past them almost indifferently and suddenly stop in front of some head with a broken nose, with a damaged eye: this is a Greek original! And the amazing power of life suddenly wafted from this fragment; the marble itself is different from that in Roman statues - not deathly white, but yellowish, see-through, luminous (the Greeks also rubbed it with wax, which gave the marble a warm tone). So gentle are the melting transitions of light and shade, so noble is the soft sculpting of the face, that one involuntarily recalls the delights of the Greek poets: these sculptures really breathe, they really are alive* * Dmitrieva, Akimova. Ancient art. Essays. - M., 1988. P. 52.

In the sculpture of the first half of the century, when there were wars with the Persians, a courageous, strict style prevailed. Then a statuette group of tyrannicides was created: a mature husband and a young man, standing side by side, make an impetuous movement forward, the younger raises his sword, the older shades him with his cloak. This is a monument to historical figures - Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who killed the Athenian tyrant Hipparchus several decades earlier - the first political monument in Greek art. At the same time, it expresses the heroic spirit of resistance and love of freedom that flared up during the era of the Greco-Persian wars. “They are not slaves to mortals, they are not subject to anyone,” says the Athenians in Aeschylus’s tragedy “The Persians.”

Battles, skirmishes, exploits of heroes... The art of the early classics is replete with these warlike subjects. On the pediments of the Temple of Athena in Aegina - the struggle of the Greeks with the Trojans. On the western pediment of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia there is a struggle between the Lapiths and the centaurs, on the metopes there are all twelve labors of Hercules. Another favorite set of motifs is gymnastic competitions; in those distant times, physical fitness and mastery of body movements were decisive for the outcome of battles, so athletic games were far from just entertainment. Since the 8th century BC. e. Gymnastic competitions were held in Olympia once every four years (their beginning was later considered the beginning of the Greek calendar), and in the 5th century they were celebrated with special solemnity, and now poets who read poetry were also present at them. The Temple of Olympian Zeus - the classic Doric peripter - was located in the center of the sacred district, where competitions took place, they began with a sacrifice to Zeus. On the eastern pediment of the temple, the sculptural composition depicted the solemn moment before the start of the horse lists: in the center is the figure of Zeus, on either side of it are statues of the mythological heroes Pelops and Oenomaus, the main participants in the upcoming competition, in the corners are their chariots drawn by four horses. According to the myth, the winner was Pelops, in whose honor the Olympic Games were established, which were later resumed, as legend has it, by Hercules himself.

The themes of hand-to-hand combat, equestrian competitions, running competitions, and discus throwing taught sculptors to depict human body in dynamics. The archaic rigidity of the figures was overcome. Now they act, they move; complex poses, bold angles, and broad gestures appear. The brightest innovator was the Attic sculptor Myron. Myron’s main task was to express the movement as fully and powerfully as possible. Metal does not allow for such precise and delicate work as marble, and perhaps that is why he turned to finding the rhythm of movement. (The name rhythm refers to the overall harmony of the movement of all parts of the body.) And indeed, the rhythm was perfectly captured by Myron. In the statues of athletes, he conveyed not only movement, but the transition from one stage of movement to another, as if stopping a moment. This is his famous “Discobolus”. The athlete bent over and swung before throwing, a second - and the disc will fly, the athlete will straighten up. But for that second his body froze in a very difficult, but visually balanced position.

Balance, a stately "ethos", is preserved in classical sculpture of a strict style. The movement of the figures is neither erratic, nor overly excited, nor too rapid. Even in the dynamic motifs of fighting, running, and falling, the feeling of “Olympic calm,” holistic plastic completeness, and self-closure is not lost. Here is a bronze statue of “Auriga”, found at Delphi, one of the few well-preserved Greek originals. It dates from the early period of the strict style - approximately around 470 BC. e.. This young man stands very straight (he stood on a chariot and drove a quadriga of horses), his legs are bare, the folds of a long chiton are reminiscent of the deep flutes of Doric columns, his head is tightly covered with a silver-plated bandage, his inlaid eyes look as if they were alive. He is restrained, calm and at the same time full of energy and will. From this bronze figure alone, with its strong, cast plastic, one can feel the full measure of human dignity as the ancient Greeks understood it.

Their art at this stage was dominated by masculine images, but, fortunately, a beautiful relief depicting Aphrodite emerging from the sea, the so-called “throne of Ludovisi”, a sculptural triptych, the upper part of which has been broken off, has also been preserved. In its central part, the goddess of beauty and love, “foam-born,” rises from the waves, supported by two nymphs who chastely protect her with a light veil. It is visible from the waist up. Her body and the bodies of the nymphs are visible through transparent tunics, the folds of clothes flow in a cascade, a stream, like streams of water, like music. On the side parts of the triptych there are two female figures: one nude, playing the flute; the other, wrapped in a veil, lights a sacrificial candle. The first is a hetaera, the second is a wife, the keeper of the hearth, like two faces of femininity, both under the patronage of Aphrodite.

The search for surviving Greek originals continues today; From time to time, lucky finds are discovered either in the ground or at the bottom of the sea: for example, in 1928, an excellently preserved bronze statue of Poseidon was found in the sea, near the island of Euboea.

But the general picture of Greek art during its heyday has to be mentally reconstructed and completed; we know only randomly preserved, scattered sculptures. And they existed in the ensemble.

Among famous masters, the name of Phidias eclipses all sculpture of subsequent generations. A brilliant representative of the age of Pericles, he said the last word plastic technique, and until now no one has dared to compare with him, although we know him only from hints. A native of Athens, he was born a few years before the Battle of Marathon and, therefore, became precisely a contemporary of the celebration of victories over the East. Speak first l he as a painter and then switched to sculpture. According to the drawings of Phidias and his drawings, under his personal supervision, the Periclean buildings were erected. Fulfilling order after order, he created marvelous statues of gods, personifying the abstract ideals of deities in marble, gold and bone. The image of the deity was developed by him not only in accordance with his qualities, but also in relation to the purpose of honor. He was deeply imbued with the idea of what this idol represented, and sculpted it with all the strength and might of a genius.

Athena, which he made by order of Plataea and which cost this city very dearly, strengthened the fame of the young sculptor. He was commissioned to create a colossal statue of Athena the patroness for the Acropolis. It reached 60 feet in height and was taller than all the surrounding buildings; From afar, from the sea, it shone like a golden star and reigned over the entire city. It was not acrolitic (composite), like the Plataean one, but was entirely cast in bronze. Another Acropolis statue, Athena the Virgin, made for the Parthenon, was made of gold and ivory. Athena was depicted in a battle suit, wearing a golden helmet with a high relief sphinx and vultures on the sides. In one hand she held a spear, in the other a piece of victory. A snake curled at her feet - the guardian of the Acropolis. This statue is considered the best assurance of Phidias after his Zeus. It served as the original for countless copies.

But the height of perfection of all the works of Phidias is considered to be his Zeus Olympian. This was the greatest work of his life: the Greeks themselves gave him the palm. He made an irresistible impression on his contemporaries.

Zeus was depicted on the throne. In one hand he held a scepter, in the other - an image of victory. The body was made of ivory, the hair was gold, the robe was gold and enameled. The throne included ebony, and bone, and precious stones. The walls between the legs were painted by Phidias's cousin, Panen; the foot of the throne was a marvel of sculpture. General impression it was, as one German scientist rightly put it, truly demonic: to a number of generations the idol seemed to be a true god; one look at him was enough to satisfy all sorrows and suffering. Those who died without seeing him considered themselves unhappy* * Gnedich P.P. World Art History. - M., 2000. P. 97...

The statue died unknown how and when: it probably burned down along with the Olympic temple. But her charms must have been great if Caligula insisted on transporting her to Rome at all costs, which, however, turned out to be impossible.

The admiration of the Greeks for the beauty and wise structure of the living body was so great that they aesthetically thought of it only in statuary completeness and completeness, allowing them to appreciate the majesty of posture and the harmony of body movements. To dissolve a person in a shapeless crowd, to show him in a random aspect, to remove him deeper, to immerse him in the shadows would be contrary to the aesthetic creed of the Hellenic masters, and they never did this, although the basics of perspective were clear to them. Both sculptors and painters showed man with extreme plastic clarity, close-up(one figure or a group of several figures), trying to place the action in the foreground, as if on a narrow stage parallel to the background plane. Body language was also the language of the soul. It is sometimes said that Greek art was alien to psychology or had not matured to it. This is not entirely true; Perhaps the art of the archaic was still non-psychological, but not the art of the classics. Indeed, it did not know that scrupulous analysis of characters, that cult of the individual that arises in modern times. It is no coincidence that the portrait in Ancient Greece was relatively poorly developed. But the Greeks mastered the art of conveying, so to speak, typical psychology - they expressed a rich range of mental movements based on generalized human types. Distracting from the shades of personal characters, Hellenic artists did not neglect the shades of experience and were able to embody a complex system of feelings. After all, they were contemporaries and fellow citizens of Sophocles, Euripides, Plato.

But still, expressiveness lay not so much in facial expressions as in body movements. Looking at the mysteriously serene Moira of the Parthenon, at the swift, playful Nike untying her sandal, we almost forget that their heads have been cut off - the plasticity of their figures is so eloquent.

Every purely plastic motif - be it the graceful balance of all members of the body, support on both legs or one, transfer of the center of gravity to an external support, the head bowed to the shoulder or thrown back - was thought by the Greek masters as an analogue of spiritual life. The body and psyche were perceived as inseparable. Characterizing the classical ideal in his Lectures on Aesthetics, Hegel said that in “the classical form of art, the human body in its forms is no longer recognized only as a sensory existence, but is recognized only as the existence and natural appearance of the spirit.”

Indeed, the bodies of Greek statues are unusually spiritual. The French sculptor Rodin said about one of them: “This headless youthful torso smiles more joyfully at the light and spring than eyes and lips could do.”* * Dmitrieva, Akimova. Ancient art. Essays. - M., 1988. P. 76.

Movements and postures in most cases are simple, natural and not necessarily associated with anything sublime. Nika unties her sandal, a boy removes a splinter from his heel, a young runner at the start line prepares to run, and Myrona the discus throws a discus. Myron's younger contemporary, the famous Polykleitos, unlike Myron, never depicted rapid movements and instantaneous states; his bronze statues of young athletes are in calm poses of light, measured movement, running in waves across the figure. The left shoulder is slightly extended, the right is abducted, the left hip is pushed back, the right is raised, the right leg is firmly on the ground, the left is slightly behind and slightly bent at the knee. This movement either does not have any “plot” pretext, or the pretext is insignificant - it is valuable in itself. This is a plastic hymn to clarity, reason, wise balance. This is Doryphoros (spearman) Polykleitos, known to us from marble Roman copies. He seems to be walking and at the same time maintaining a state of rest; the positions of the arms, legs and torso are perfectly balanced. Polykleitos was the author of the treatise “Canon” (which has not come down to us, it is known from mentions of ancient writers), where he theoretically established the laws of proportions of the human body.

The heads of Greek statues, as a rule, are impersonal, that is, little individualized, reduced to a few variations of a general type, but this general type has a high spiritual capacity. In the Greek type of face, the idea of the “human” in its ideal version triumphs. The face is divided into three parts of equal length: forehead, nose and lower part. Correct, gentle oval. The straight line of the nose continues the line of the forehead and forms a perpendicular to the line drawn from the beginning of the nose to the opening of the ear (straight facial angle). Oblong section of rather deep-set eyes. A small mouth, full convex lips, the upper lip is thinner than the lower and has a beautiful smooth cut like a cupid's bow. The chin is large and round. Wavy hair softly and tightly fits the head, without interfering with the visibility of the rounded shape of the skull.

This classic beauty may seem monotonous, but, representing the expressive “natural appearance of the spirit,” it lends itself to variation and is capable of embodying Various types ancient ideal. A little more energy in the shape of the lips, in the protruding chin - before us is the strict virgin Athena. There is more softness in the contours of the cheeks, the lips are slightly half-open, the eye sockets are shaded - before us is the sensual face of Aphrodite. The oval of the face is closer to a square, the neck is thicker, the lips are larger - this is already the image of a young athlete. But the basis remains the same strictly proportional classical appearance.

However, there is no place in it for something that, from our point of view, is very important: the charm of the uniquely individual, the beauty of the wrong, the triumph of the spiritual principle over bodily imperfection. The ancient Greeks could not give this; for this, the original monism of spirit and body had to be broken, and aesthetic consciousness had to enter the stage of their separation - dualism - which happened much later. But Greek art also gradually evolved towards individualization and open emotionality, concreteness of experiences and characterization, which becomes obvious already in the era of the late classics, in the 4th century BC. e.

At the end of the 5th century BC. e. The political power of Athens was shaken, undermined by the long Peloponnesian War. At the head of Athens's opponents was Sparta; it was supported by other states of the Peloponnese and provided financial assistance by Persia. Athens lost the war and was forced to conclude an unfavorable peace; they retained their independence, but the Athenian Maritime Union collapsed, monetary reserves dried up, and the internal contradictions of the policy intensified. Athenian democracy managed to survive, but democratic ideals faded, free expression of will began to be suppressed by cruel measures, an example of this is the trial of Socrates (in 399 BC), which imposed a death sentence on the philosopher. The spirit of cohesive citizenship is weakening, personal interests and experiences are isolated from public ones, and the instability of existence is felt more alarmingly. Critical sentiment is growing. A person, according to Socrates’ behest, begins to strive to “know himself” - himself as an individual, and not just as a part of the social whole. The work of the great playwright Euripides, in whom the personal principle is much more emphasized than in his older contemporary Sophocles, is aimed at understanding human nature and characters. According to Aristotle's definition, Sophocles “represents people as they should be, and Euripides as they really are.”

In the plastic arts, generalized images still predominate. But the spiritual resilience and cheerful energy that breathes the art of early and mature classics gradually give way to the dramatic pathos of Skopas or the lyrical, tinged with melancholy, contemplation of Praxiteles. Scopas, Praxiteles and Lysippos - these names are associated in our minds not so much with certain artistic individuals (their biographies are unclear, and almost no original works of theirs have survived), but with the main trends of the late classics. Just like Myron, Polykleitos and Phidias personify the features of a mature classic.

And again, plastic motives are indicators of changes in the worldview. The characteristic pose of the standing figure changes. In the archaic era, statues stood completely straight, frontally. Mature classics enliven and animate them with balanced, smooth movements, maintaining balance and stability. And the statues of Praxiteles - the resting Satyr, Apollo Saurocton - rest with lazy grace on pillars, without them they would have to fall.

The thigh on one side is arched very strongly, and the shoulder is lowered low towards the thigh - Rodin compares this position of the body with a harmonica, when the bellows are compressed on one side and spread apart on the other. External support is required for balance. This is a dreamy rest position. Praxiteles follows the traditions of Polykleitos, uses the motives of movements he found, but develops them in such a way that a different internal content shines through in them. “The Wounded Amazon” Polykletai also leans on a half-column, but she could have stood without it, her strong, energetic body, even suffering from a wound, stands firmly on the ground. Praxiteles' Apollo is not hit by an arrow, he himself aims at a lizard running along a tree trunk - an action that would seem to require strong-willed composure, yet his body is unstable, like a swaying stem. And this is not a random detail, not a whim of the sculptor, but a kind of new canon in which a changed view of the world finds expression.

However, not only the nature of movements and poses changed in sculpture of the 4th century BC. e. For Praxiteles, the range of his favorite topics becomes different; he moves away from heroic subjects into the “light world of Aphrodite and Eros.” He sculpted the famous statue of Aphrodite of Knidos.

Praxiteles and the artists of his circle did not like to depict the muscular torsos of athletes; they were attracted by the delicate beauty of the female body with the soft flow of volumes. They preferred the type of youth, distinguished by “first youth and effeminate beauty.” Praxiteles was famous for his special softness of modeling and skill in processing the material, his ability to convey the warmth of a living body in cold marble2.

The only surviving original of Praxiteles is considered to be the marble statue “Hermes with Dionysus”, found in Olympia. Naked Hermes, leaning on a tree trunk where his cloak has been carelessly thrown, holds little Dionysus on one bent arm, and in the other a bunch of grapes, to which the child is reaching (the hand holding the grapes is lost). All the charm of pictorial marble processing is in this statue, especially in the head of Hermes: transitions of light and shadow, the finest “sfumato” (haze), which, many centuries later, was achieved in painting by Leonardo da Vinci.

All other works of the master are known only from mentions of ancient authors and later copies. But the spirit of Praxiteles’ art lingers over the 4th century BC. e., and best of all it can be felt not in Roman copies, but in small Greek plastic, in Tanagra clay figurines. They were produced at the end of the century in large quantities, it was a kind of mass production with the main center in Tanagra. (A very good collection of them is kept in the Leningrad Hermitage.) Some figurines reproduce famous large statues, others simply give various free variations of the draped female figure. The living grace of these figures, dreamy, thoughtful, playful, is an echo of the art of Praxiteles.

Almost as little remains of the original works of the chisel Skopas, an older contemporary and antagonist of Praxiteles. Debris remained. But the wreckage also speaks volumes. Behind them rises the image of a passionate, fiery, pathetic artist.

He was not only a sculptor, but also an architect. As an architect, Skopas created the temple of Athena in Tegea and he also supervised its sculptural decoration. The temple itself was destroyed long ago, by the Goths; Some fragments of sculptures were found during excavations, among them a remarkable head of a wounded warrior. There were no others like her in the art of the 5th century BC. e., there was no such dramatic expression in the turn of the head, such suffering in the face, in the gaze, such mental tension. In his name, the harmonic canon adopted in Greek sculpture: the eyes are set too deep and the bend of the brow ridges is dissonant with the outlines of the eyelids.

What Skopas's style was in multi-figure compositions is shown by partially preserved reliefs on the frieze of the Halicarnassus Mausoleum - a unique structure, ranked in ancient times as one of the seven wonders of the world: the peripterus was erected on a high base and topped with a pyramidal roof. The frieze depicted the battle of the Greeks with the Amazons - male warriors with female warriors. Skopas did not work on it alone, together with three sculptors, but, guided by the instructions of Pliny, who described the mausoleum, and stylistic analysis, the researchers determined which parts of the frieze were made in Skopas’ workshop. More than others, they convey the drunken fervor of battle, the “ecstasy in battle,” when both men and women surrender to it with equal passion. The movements of the figures are impetuous and almost lose their balance, directed not only parallel to the plane, but also inward, into depth: Skopas introduces a new sense of space.

"Maenad" enjoyed great fame among his contemporaries. Skopas depicted a storm of Dionysian dance, straining the entire body of the Maenad, convulsively arching her torso, throwing back her head. The statue of the Maenad is not designed for frontal viewing, it needs to be viewed from different sides, each point of view reveals something new: sometimes the body is likened in its arch to a drawn bow, sometimes it seems bent in a spiral, like a tongue of flame. One cannot help but think: the Dionysian orgies must have been serious, not just amusement, but truly “mad games.” The Mysteries of Dionysus were allowed to be held only once every two years and only on Parnassus, but at that time the frantic bacchantes discarded all conventions and prohibitions. To the beat of tambourines, to the sound of tympanums, they rushed and whirled in ecstasy, driving themselves into a frenzy, letting down their hair, tearing their clothes. The maenad of Skopas held a knife in her hand, and on her shoulder was a kid that she had torn to pieces 3.

Dionysian festivals were a very ancient custom, like the cult of Dionysus itself, but in art the Dionysian element had not previously broken through with such force, with such openness as in the statue of Skopas, and this is obviously a symptom of the times. Now clouds were gathering over Hellas, and reasonable clarity of spirit was disrupted by the desire to forget, to throw off the shackles of restrictions. Art, like a sensitive membrane, responded to changes in the social atmosphere and transformed its signals into its own sounds, its own rhythms. The melancholic languor of Praxiteles' creations and the dramatic impulses of Scopas are just different reactions to the general spirit of the times.

The young man’s marble tombstone belongs to Skopas’s circle, and perhaps to himself. To the right of the young man stands his old father with an expression of deep thought; one can feel that he is asking the question: why did his son leave in the prime of his youth, and he, the old man, remained to live? The son looks ahead and no longer seems to notice his father; he is far from here, in the carefree Champs Elysees - the abode of the blessed.

The dog at his feet is one of the symbols of the afterlife.

Here it is appropriate to talk about Greek tombstones in general. There are relatively many of them preserved, from the 5th, and mainly from the 4th century BC. e.; their creators are, as a rule, unknown. Sometimes the relief of a tombstone stele depicts only one figure - the deceased, but more often his loved ones are depicted next to him, one or two, who say goodbye to him. In these scenes of farewell and parting, strong grief and grief are never expressed, but only quiet; sad thoughtfulness. Death is peace; the Greeks personified her not in a terrible skeleton, but in the figure of a boy - Thanatos, the twin of Hypnos - a dream. The sleeping baby is also depicted on the Skopasovsky tombstone of the young man, in the corner at his feet. The surviving relatives look at the deceased, wanting to capture his features in their memory, sometimes they take him by the hand; he (or she) himself does not look at them, and one can feel relaxation and detachment in his figure. In the famous tombstone of Gegeso (late 5th century BC), a standing maid gives her mistress, who is sitting in a chair, a box of jewelry, Hegeso takes a necklace from it with a familiar, mechanical movement, but she looks absent and drooping.

Authentic tombstone from the 4th century BC. e. The works of the Attic master can be seen in the State Museum of Fine Arts. A.S. Pushkin. This is the tombstone of a warrior - he holds a spear in his hand, next to him is his horse. But the pose is not at all militant, the body members are relaxed, the head is lowered. On the other side of the horse stands a farewell; he is sad, but one cannot be mistaken about which of the two figures depicts the deceased and which one depicts the living, although they would seem to be similar and of the same type; Greek masters knew how to make one feel the transition of the deceased into the valley of shadows.

Lyrical scenes of the last farewell were also depicted on funeral urns, where they are more laconic, sometimes just two figures - a man and a woman - shaking hands with each other.

But even here it is always clear which of them belongs to the kingdom of the dead.

There is some special chastity of feeling in Greek tombstones with their noble restraint in the expression of sadness, something completely opposite to Bacchic ecstasy. The tombstone of the youth attributed to Skopas does not violate this tradition; it stands out from others, in addition to its high plastic qualities, only by the philosophical depth of the image of a thoughtful old man.

Despite all the contrast in the artistic natures of Scopas and Praxiteles, both of them are characterized by what can be called an increase in picturesqueness in plastic - the effects of chiaroscuro, thanks to which the marble seems alive, which is what the Greek epigrammatists emphasize every time. Both masters preferred marble to bronze (whereas bronze predominated in early classical sculpture) and achieved perfection in processing its surface. The strength of the impression made was facilitated by the special qualities of the types of marble that the sculptors used: translucency and luminosity. Parian marble transmitted light by 3.5 centimeters. Statues made of this noble material looked both humanly alive and divinely incorruptible. Compared with the works of early and mature classics, late classical sculptures lose something, they do not have the simple grandeur of the Delphic “Auriga,” or the monumentality of Phidias’ statues, but they gain in vitality.

History has preserved many more names of outstanding sculptors of the 4th century BC. e. Some of them, cultivating life-likeness, brought it to the point beyond which genre and specificity begins, thus anticipating the tendencies of Hellenism. Demetrius of Alopeka was distinguished by this. He attached little importance to beauty and consciously sought to portray people as they were, without hiding large bellies and bald spots. His specialty was portraits. Demetrius made a portrait of the philosopher Antisthenes, polemically directed against the idealizing portraits of the 5th century BC. e., - His Antisthenes is old, flabby and toothless. The sculptor could not spiritualize ugliness, make it charming; such a task was impossible within the boundaries of ancient aesthetics. Ugliness was understood and portrayed simply as a physical defect.

Others, on the contrary, tried to support and cultivate the traditions of mature classics, enriching them with greater grace and complexity of plastic motifs. This was the path followed by Leochares, who created the statue of Apollo Belvedere, which became the standard of beauty for many generations of neoclassicists until the end of the twentieth century. Johann Winckelmann, author of the first scientific History of Art of Antiquity, wrote: “The imagination cannot create anything that would surpass the Vatican Apollo with his more than human proportionality of a beautiful deity.” For a long time, this statue was regarded as the pinnacle of ancient art; the “Belvedere idol” was synonymous with aesthetic perfection. As is often the case, over-the-top praise over time caused the opposite reaction. When the study of ancient art advanced far ahead and many of its monuments were discovered, the exaggerated assessment of the statue of Leochares gave way to an understated one: it began to be found pompous and mannered. Meanwhile, Apollo Belvedere is a truly outstanding work in its plastic merits; the figure and gait of the ruler of the muses combines strength and grace, energy and lightness, walking on the ground, he at the same time soars above the ground. Moreover, its movement, in the words of the Soviet art critic B. R. Vipper, “is not concentrated in one direction, but, as if rays, diverge in different directions.” To achieve such an effect required the sophisticated skill of a sculptor; the only trouble is that the calculation for the effect is too obvious. Apollo Leochara seems to invite one to admire his beauty, while the beauty of the best classical statues does not publicly declare itself: they are beautiful, but they do not show off. Even Praxitela's Aphrodite of Cnidus wants to hide rather than demonstrate the sensual charm of her nakedness, and earlier classical statues filled with calm self-sufficiency, excluding any demonstrativeness. It should therefore be recognized that in the statue of Apollo Belvedere the ancient ideal begins to become something external, less organic, although in its own way this sculpture is remarkable and marks a high level of virtuoso skill.

The last great sculptor took a big step towards “naturalness” Greek classics- Lysippos. Researchers attribute him to the Argive school and claim that he had a completely different direction than the Athenian school. In essence, he was her direct follower, but, having adopted her traditions, he stepped further. In his youth, the artist Eupomp answered his question: “Which teacher should I choose?” - answered, pointing to the crowd crowded on the mountain: “This is the only teacher: nature.”

These words sank deep into the soul of the brilliant young man, and he, not trusting the authority of the Polykleitan canon, took up the exact study of nature. Before him, people were sculpted in accordance with the principles of the canon, that is, in full confidence that true beauty lies in the proportionality of all forms and in the proportion of people of average height. Lysippos preferred a tall, slender figure. His limbs became lighter, his stature taller.

Unlike Scopas and Praxiteles, he worked exclusively in bronze: fragile marble requires stable balance, and Lysippos created statues and statuary groups in dynamic states, in complex actions. He was inexhaustibly varied in the invention of plastic motifs and very prolific; they said that after completing each sculpture he put a gold coin in the piggy bank, and in this way he accumulated one and a half thousand coins, that is, he allegedly made one and a half thousand statues, some of very large sizes, including a 20-meter statue of Zeus. Not a single work of his has survived, but a fairly large number of copies and repetitions, dating back either to the originals of Lysippos or to his school, give an approximate idea of the master’s style. In terms of plot, he clearly preferred male figures, as he loved to depict the difficult exploits of husbands; His favorite hero was Hercules. In understanding plastic form, Lysippos' innovative achievement was the reversal of the figure in the space surrounding it on all sides; in other words, he did not think of the statue against the background of any plane and did not assume one, main point of view from which it should be viewed, but counted on walking around the statue. We have seen that Skopas' Maenad was already built on the same principle. But what was the exception with previous sculptors became the rule with Lysippos. Accordingly, he gave his figures effective poses, complex turns, and treated them with equal care not only from the front side, but also from the back.

In addition, Lysippos created a new sense of time in sculpture. The former classical statues, even if their poses were dynamic, looked unaffected by the flow of time, they were outside of it, they were, they were at rest. The heroes of Lysippos live in the same real time as living people, their actions are included in time and are transient, the presented moment is ready to be replaced by another. Of course, Lysippos had predecessors here too: we can say that he continued the traditions of Myron. But even the Discobolus of the latter is so balanced and clear in his silhouette that he seems “abiding” and static in comparison with Lysippos’ Hercules fighting a lion, or Hermes, who for a minute (precisely for a minute!) sat down to rest on a roadside stone in order to continue later flying on your winged sandals.

Whether the originals of these sculptures belonged to Lysippos himself or his students and assistants has not been established precisely, but undoubtedly he himself made the statue of Apoxyomenes, a marble copy of which is in the Vatican Museum. A young naked athlete, with his arms outstretched, uses a scraper to remove the accumulated dust. He was tired after the struggle, relaxed slightly, even seemed to stagger, spreading his legs for stability. Strands of hair, treated very naturally, stuck to the sweaty forehead. The sculptor did everything possible to give maximum naturalness within the framework of the traditional canon. However, the canon itself has been revised. If you compare Apoxyomenes with Doryphorus of Polykleitos, you can see that the proportions of the body have changed: the head is smaller, the legs are longer. Doryphoros is heavier and stockier compared to the flexible and slender Apoxyomenes.

Lysippos was the court artist of Alexander the Great and painted a number of his portraits. There is no flattery or artificial glorification in them; The head of Alexander, preserved in a Hellenistic copy, is executed in the traditions of Skopas, somewhat reminiscent of the head of a wounded warrior. This is the face of a man who lives a tense and difficult life, whose victories are not easy to achieve. The lips are half-open, as if breathing heavily; despite his youth, there are wrinkles on his forehead. However, the classic type of face with proportions and features legitimized by tradition has been preserved.

The art of Lysippos occupies the border zone at the turn of the classical and Hellenistic eras. It is still true to classical concepts, but it is already undermining them from the inside, creating the basis for a transition to something else, more relaxed and more prosaic. In this sense, the head of a fist fighter is indicative, belonging not to Lysippos, but, possibly, to his brother Lysistratus, who was also a sculptor and, as they said, was the first to use masks removed from the model’s face for portraits (which was widespread in Ancient Egypt, but completely alien to Greek art). It is possible that the head of a fist fighter was also made using the mask; it is far from the canon, and far from the ideal ideas of physical perfection that the Hellenes embodied in the image of an athlete. This winner in a fist fight is not at all like a demigod, just an entertainer for an idle crowd. His face is rough, his nose is flattened, his ears are swollen. This type of “naturalistic” images subsequently became common in Hellenism; an even more unsightly fist fighter was sculpted by the Attic sculptor Apollonius already in the 1st century BC. e.

What had previously cast shadows on the bright structure of the Hellenic worldview came at the end of the 4th century BC. e.: decomposition and death of the democratic polis. This began with the rise of Macedonia, the northern region of Greece, and the virtual capture of all Greek states Macedonian king Philip II. The 18-year-old son of Philip, Alexander, the future great conqueror, took part in the Battle of Chaeronea (in 338 BC), where the troops of the Greek anti-Macedonian coalition were defeated. Starting with a victorious campaign against the Persians, Alexander advanced his army further east, capturing cities and founding new ones; as a result of a ten-year campaign, a huge monarchy was created, stretching from the Danube to the Indus.

Alexander the Great tasted the fruits of the highest Greek culture in his youth. His teacher was the great philosopher Aristotle, and his court artists were Lysippos and Apelles. This did not prevent him, having captured the Persian state and taken the throne of the Egyptian pharaohs, from declaring himself a god and demanding that he be given divine honors in Greece as well. Unaccustomed to eastern customs, the Greeks chuckled and said: “Well, if Alexander wants to be a god, let him be” - and officially recognized him as the son of Zeus. The Orientalization that Alexander began to instill was, however, a more serious matter than the whim of a conqueror intoxicated with victories. It was a symptom of the historical turn of ancient society from slave-owning democracy to the form that had existed since ancient times in the East - to the slave-owning monarchy. After the death of Alexander (and he died young), his colossal but fragile power disintegrated, the spheres of influence were divided among themselves by his military leaders, the so-called diadochi - successors. The states that emerged again under their rule were no longer Greek, but Greco-Eastern. The era of Hellenism has arrived - the unification under the auspices of the monarchy of Hellenic and Eastern cultures.

Full text search:

Home > Abstract >Culture and art

ABSTRACT

In the discipline "Russian and foreign art"

on the topic “Sculpture of Ancient Greece during the Classical Age. Leading masters and main monuments"

Saint Petersburg

1. Introduction 3

2.1. Pythagoras of Rhegium 4

2.2. Miron 5

3. Sculpture of Ancient Greece from the High Classical era 7

3.1. Phidias 7

3.2. Polykleitos 10

4. Sculpture of Ancient Greece of the late classical era 11

4.1. Praxiteles 11

4.2. Skopas 13

4.3. Lysippos 14

5. Conclusion 16

6. References 17

4. Universal encyclopedia “Around the World” [electronic resource] – Culture and Education: Fine arts, sculpture, architecture. – 2001-2009. – Access mode: http://www.krugosvet.ru, free. - Cap. from the screen. 17

1. Introduction

At the end of the 6th century. BC e. Many changes took place in Greek cities. The tyrannies of the past were replaced by slave-owning democracy. Turbulent internal political events were accompanied by the outbreak that broke out at the beginning of the 5th century. BC e. a fierce and prolonged war with the Persians (only in 449 BC was peace concluded).

The significance of the Greco-Persian conflict goes far beyond the boundaries of the dispute between two ancient peoples. It was a clash of opposing worldviews: the Hellenic cities with their new democratic aspirations opposed the despotic rule of the Persian monarchy. It is difficult to say how European civilization would have developed if the Persians had strangled the Hellenic culture.

It was during this period of trials that befell the Greeks that a clearly expressed turning point in art occurred. The archaic, largely conventional reproduction of reality was replaced by a classical one - closer to the embodiment of visible reality as it seemed to man. The convention inherent in the monuments of art of all times did not disappear completely, but only took on new forms in plastic and pictorial images that were outwardly closer to reality.

The classical period in Hellenic art, according to generally accepted periodization, lasted about two centuries and fell on the V-IV centuries. BC e., however, within its limits it is necessary to distinguish several stages.

In the era of the early classics (the first half of the 5th century BC), artistic images are characterized by increased dynamism of forms, many elements of late archaic convention are still preserved, and emotional tension caused by the general situation during the years of fierce battles with the Persians is felt. Later, in the second half of the 5th century. BC e., when the Greek world reaped the fruits of its victory in the war, the images of art acquired a predominantly confidently calm, proud and solemn character. This time of the heyday of Hellenic culture, when outstanding sculptors Polykleitos, Phidias and other great masters worked, is called high classics. At the end of the 5th century. BC e. there was a transition to the late classics (IV century BC). Monuments with a new emotional sound - sometimes extremely disturbing, sometimes elegiac and dreamy - arose in the workshops of such sculptors as Scopas, Praxiteles, Lysippos.

2. Sculpture of Ancient Greece from the Early Classical era

The largest sculptors of the early classics are Pythagoras of Rhegium and Myron. We judge the work of famous Greek sculptors mainly from literary evidence and later copies of their works.

2.1. Pythagoras of Rhegium

Pythagoras of Rhegium was born on the island of Samos and subsequently moved to Rhegium in southern Italy. Pythagoras of Rhegium was a contemporary and rival of Myron. They spoke of him as the first sculptor in whose work an attempt was made to maintain rhythm and proportionality. Ancient sources depict Pythagoras as one of the most brilliant masters of a strict style. Pythagoras worked on orders from many Greek cities in the Balkans, eastern and western Greece. His creative life supposedly lasted 40 years, from 480 to 440 BC. Judging by the brief remarks of ancient writers on his style, Pythagoras was an innovator. He was the first to depict “muscles and veins” and to interpret hair more realistically. According to legend, Pythagoras of Rhegium is also the author of the term “symmetry,” which he used to designate a spatial pattern in the arrangement of identical parts of a figure or the figures themselves. The sculptor’s particular interest was focused on the figures of athletes, who, after the end of the wars, acquired a very special, almost heroic status in the art of Hellas.

Based on these data in small bronzes (Pythagoras was a bronzer) and among Roman copies reflecting works of a strict style, scientists selected those that best satisfied all these characteristics. Most likely, the image of an athlete, depicted in the bronze figurine of the Athlete from Aderno (c. 460 BC), goes back to Pythagoras. The young man is depicted standing, with his hands slightly spread to the sides: he was pouring a libation from a bowl. He seems to be standing calmly, but in fact there is no rigidity in his figure: he turns his head towards the supporting leg. There is a “tectonic” concept in the construction of the figure, presented in a very mature and original way. However, the athlete from Aderno, standing, continues to move jerkily; it seems that he froze only for a minute and immobility is an unusual state for him. Despite the fact that the figure is designed for frontal perception, the plasticity of the body is developed subtly and involves a circular walk.

The reflection of the Pythagorean statue of the cithared Cleon, made for Thebes, is seen in a bronze figurine from the Hermitage (c. 460 - 450 BC). The Hermitage lyre player is almost a boy, he sits on a rock, playing an instrument; the upper part of the body is naked, the lower part is covered with a cloak. The young man is cheerful and energetic, very relaxed, and it seems, as in the case of the athlete from Aderno, that the action did not freeze at the moment the master fixed it - it continues. The figurine is well made, it is also round, with an original contrast of loaded and free parts.

Among the works of Pythagoras is the original statue of the lame Philoctetes. Pliny reports that the viewer, looking at Philoctetes, felt the same acute pain that the hero experienced when bitten on the heel by a snake on the island of Lemnos. The story of Philoctetes, an outstanding archer who wielded the bow of Hercules, is intertwined with the history of the Trojan War: the hero will be taken to Troy by the Achaeans from the island of Lemnos, and he will be destined to hit the Trojan Paris with an arrow. It is important that Pythagoras does not choose a brilliant act in the fate of Philoctetes, but, on the contrary, a difficult, suffering one. The choice of a physically handicapped - lame - hero is indicative of a strict style with its love for extraordinary events, but still unique.

Apparently, Pythagoras was not only a “singer of physical power,” as a number of scientists believe. Even in calmly standing figures it remained dynamic and pulsating. His art glorifies the courageous heroes of post-war Hellas in the 5th century. BC. in a style that represents a unique synthesis of Ionian, Dorian and southern Italian traditions.

2.2. Miron

Myron, Greek sculptor of the 5th century. BC, representative of the transitional period in sculpture from the early classics to the art of Periclean times. Born in the town of Eleuthera on the border of Attica and Boeotia. The ancients characterize him as the greatest realist and expert in anatomy, who, however, did not know how to give life and expression to faces. He depicted gods, heroes and animals; according to reviews of ancient connoisseurs, he sought to convey maximum tension in the image. His activity dates back to approximately the middle of the 5th century. - the time of victories of three athletes, whose statues he sculpted in 456, 448 and 444 BC. Myron was an older contemporary of Phidias and Polykleitos and was considered one of the greatest sculptors of his time. He worked in bronze, but none of his works have survived; they are known mainly from copies.

His most famous work is “The Discus Thrower” (c. 450 BC), an athlete intending to throw a discus, a statue that has survived to this day in several copies, of which the best is made of marble and is located in the Massimi Palace (in Rome).

The statue was bronze. The young man is depicted at the moment of preparation for throwing the discus, in a dynamic pose, as if frozen for a moment. A second later, he straightened out like a spring and threw his disk. The figure is constructed in such a way that the whole body of the young man is not only bent, but also rotates: the free left leg rests on the toes, the torso is extremely tense, the chest and face are turned full face, but the gaze is directed not at the viewer, not directly, but at the disk. The discus thrower has excellent proportions and is anatomically perfectly built. The figure is very naturalistic in its individual parts and at the same time completely ideal as a whole. The head of the Discobolus, considered separately, has a strong asymmetry of the two halves: the left cheek is rounder, the eye is narrower and more elongated, the eyebrow is curved more steeply, the mouth is slanted to the side. But since the head is lowered down and is seen by the viewer in a difficult position, these adjustments are designed to harmonize the general. This bold and original figure, with a bright ideal space, intruding into the surrounding world with an angle and suggesting an instant change of disposition (in a minute, instead of a head, a disk will cut through the front space) - the statue of the Discobolus is built with an orientation towards the frontal point of view. It is not round, not voluminous. When viewed in profile, it shrinks and narrows, losing its volume, and its rear view is incomplete. Myron’s magnificent and dynamic design is realized in a flattened – planimetric – scheme. However, this is by no means a shortcoming of Myron, but a distinctive feature of his talent. Many Athenian sculptors, including Phidias, were more inclined towards such facade aspects than the round Dorian form.

Another famous monument of Myron is the group of Athena with Marsyas, (c. 450 BC), dedicated to the Acropolis of Athens. It was reconstructed on the basis of a number of sources: mentions of ancient authors, an image on an Attic red-figure vase around 440 BC. (Berlin, State museums) and Roman copies.

Myron presented a situation typical of the strict style: the clash of the Olympian goddess with a lower deity, the strong man Marsyas. The legend tells how Athena invented the flute, but when she saw her reflection on the surface of the water with puffy cheeks, she threw the instrument away in indignation. The strong Marsyas crept up to grab the flute, but Athena threatened him with a curse and forbade him to touch the flute.

Myron organically combined his statues. He connects them both psychologically - with a single flute motif, a single action, and optically - with contrast and consonance of rhythmic movements. A marble copy of "Marsyas" (the original was cast in bronze) stood for many years in the Lateran Museum as an independent statue, until, based on images on coins and the story of Pausanias, it was possible to establish that "Marsyas" represented part of a group.

3. Sculpture of Ancient Greece from the High Classical era

In the art of high classics, ideas and feelings that were universal in their essence were embodied with particular force. Striving to express the deep, hidden meaning of an artistic image as clearly and generally as possible, the masters freed themselves as much as possible from everything that seemed to them too detailed and specific.

Art forms throughout the 5th century. BC e. changed very noticeably. The dynamics and mobility of the predominantly heroic images of the early classics, the character of which was determined by the tension of all the forces of the Hellenes during the Persian wars, gave way to a sublime peace that corresponded to the mood of the Greeks, who realized the significance of their victory.

Athens, where the main finances of the union were concentrated, prospered. These are the years of the reign of Pericles, who stood at the head of the Athenian democracy, a time of intense activity of the great sculptors Phidias and Polycletus. Athens, destroyed by the Persians, was rebuilt, and the most talented architects, sculptors, and painters came there to create a magnificent ensemble of buildings on the Acropolis. Athens became one of the most famous and beautiful cities of that time. The pinnacle of ancient Greek sculpture was, apparently, the chrysoelephantine statues of Athena Parthenos and Olympian Zeus by Phidias (both have not survived).

3.1. Phidias

Phidias, an ancient Greek sculptor considered by many to be the greatest artist of antiquity. Phidias was a native of Athens, his father's name was Charmides. Phidias studied the skill of a sculptor in Athens at the school of Hegeias and in Argos at the school of Agelas (in the latter, perhaps at the same time as Polykleitos). Among the existing statues there is not a single one that undoubtedly belonged to Phidias. Our knowledge of his work is based on descriptions of ancient authors, on the study of later copies, as well as surviving works that are attributed to Phidias with more or less certainty.

Among Phidias's early works, created c. 470–450 BC, we should mention the cult statue of Athena Areia in Plataea, made of gilded wood (clothing) and Pentelic marble (face, arms and legs). By the same period, approx. 460 BC, refers to the memorial complex at Delphi, built in honor of the Athenian victory over the Persians in the Battle of Marathon. At the same time (c. 456 BC), and also using funds from the booty captured in the Battle of Marathon, Phidias installed a colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos (Protector) on the Acropolis. Another bronze statue of Athena on the Acropolis, the so-called. Athena Lemnia, who holds a helmet in her hand, was created by Phidias c. 450 BC by order of Attic colonists sailing to the island of Lemnos. Perhaps the two statues located in Dresden, as well as the head of Athena from Bologna, are copies of it.

The chrysoelephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Zeus at Olympia was considered in ancient times to be the masterpiece of Phidias. Dion Chrysostomos and Quintilian (1st century AD) say that thanks to the unsurpassed beauty and godly creation of Phidias, religion itself was enriched, and Dion adds that anyone who happened to see this statue forgets all his sorrows and adversities. A detailed description of the statue, considered one of the seven wonders of the world, is available from Pausanias. Zeus was depicted sitting. In the palm of his right hand stood the goddess Nike, and in his left he held a scepter, on top of which sat an eagle. Zeus was bearded and long-haired, with a laurel wreath on his head. The seated figure almost touched the ceiling with his head, so that it seemed that if Zeus stood up, he would blow the roof off the temple. The throne was richly decorated with gold, ivory and precious stones. In the upper part of the throne above the head of the statue, the figures of the three Charites were placed on one side, and the three seasons on the other; dancing Niki were depicted on the legs of the throne. On the crossbars between the legs of the throne stood statues representing the Olympic competitions and the battle of the Greeks (led by Hercules and Theseus) with the Amazons. The pedestal of the throne, made of black stone, was decorated with golden reliefs depicting the gods, in particular Eros, who meets Aphrodite emerging from the sea waves, and Peyto (goddess of persuasion) crowning her with a wreath. A statue of Olympian Zeus or one of his heads was depicted on coins that were minted in Elis. There was no clarity regarding the time of creation of the statue in antiquity, but since the construction of the temple was completed ca. 456 BC, the statue was most likely erected no later than c. 450 BC (there have now been renewed attempts to place Zeus from Olympia to a time after the Athena Parthenos).

When Pericles launched extensive construction in Athens, Phidias headed all the work on the Acropolis, among other things, the construction of the Parthenon, which was carried out by the architects Ictinus and Callicrates in 447–438. BC. The Parthenon, the temple of the patron goddess of the city of Athens, one of the most famous creations of ancient architecture, was a Doric peripterus. The abundant plastic decoration of the temple was carried out by a large group of sculptors, working under the supervision of Phidias and, probably, according to his sketches (the most famous are the relief friezes of the Parthenon, now in the British Museum, and the fragmentarily preserved statues from the pediments).

The cult chrysoelephantine statue of Athena Parthenos that stood in the temple, which was completed in 438 BC, was sculpted by Phidias himself. The description of Pausanias and numerous copies give a fairly clear idea of it. Athena was depicted standing at full height, wearing a long chiton hanging in heavy folds. On the palm of Athena's right hand stood the winged goddess Nike; on Athena's chest was an aegis with the head of Medusa; in her left hand the goddess held a spear, and a shield was leaning against her feet. The sacred snake of Athena (Pausanias calls it Erichthonius) curled up around the spear. The statue's pedestal depicted the birth of Pandora (the first woman). As Pliny the Elder writes, on the outside of the shield there was a battle with the Amazons, on the inside there was a fight between gods and giants, and on Athena’s sandals there was an image of a centauromachy. On the head of the goddess there was a helmet crowned with three crests, the middle of which represented a sphinx, and the side ones were griffins. Athena had jewelry: necklaces, earrings, bracelets.

The similarity of the style with the sculptures and reliefs of the Parthenon is felt in the statues of Demeter (copies of it are in Berlin and Cherchel, Algeria) and Kore (copy in the Villa Albani). The motifs of both statues are used in the famous large motif relief from Eleusis (Athens, Archaeological Museum), a Roman copy of which is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

The folds of Cora's robe are similar in style to the drapery of the standing Zeus statue, a copy of which is kept in Dresden, and the torso, possibly a fragment of the original, is in Olympia. Similar in style to the Parthenon frieze is Anadumen (a young man tying a bandage around his head); it may have been created as a response to the Diadumen of Polykleitos. The statue of Phidias is much more natural in terms of posture and gesture, but somewhat rougher. Together with Polykleitos and Cresilaus, Phidias took part in the competition for a statue of a wounded Amazon for the temple of Artemis in Ephesus and took second place after Polykleitos; a copy of his statue is considered to be the so-called. Amazon Mattei (Vatican). Wounded in the thigh, the Amazon tucked her chiton into her belt; to reduce the pain, she leans on the spear, grasping it with both hands, with the right one raised above her head. As with the Athena Parthenos and the Parthenon reliefs, rich content is contained here in a simple form.

The creations of Phidias are grandiose, majestic and harmonious; form and content are in perfect balance in them. The master's students, Alkamen and Agorakrit, continued to work in his style in the last quarter of the 5th century. BC, and many other sculptors, among them Kephisodotus, - and in the first quarter of the 4th century. BC.

3.2. Polykleitos

Polykleitos (5th century BC), ancient Greek sculptor and art theorist, worked ca. 460–420 BC. Born in Sikyon c. 480 u/ BC, studied in Argos with Ageladus, possibly at the same time as Phidias, and later headed the Argive school of sculptors. It was believed that no one could compare with Polykleitos in depicting athletes, while Phidias was recognized as the first in depicting gods. Around 460–450 BC. Polykleitos created several statues of the victors Olympic Games, incl. Kiniska (its pedestal was found during excavations at Olympia). Perhaps its copy is a statue of an athlete putting on a wreath (the so-called Westmacott Youth from the British Museum). Other works of the early period of Polykleitos's work are the Discophore (The Disc Bearer, the best copies in Wellesley College near Boston, USA, and in the Vatican) and Hermes (an idea of it can be gleaned from a bronze figurine from the British Museum).

However, Polykleitos's most famous work is created c. 450–440 BC. Doryphoros (Spearman). The best copies of this statue are in Naples, the Vatican and Florence; the best surviving copy of the head of Doryphorus was made in bronze by the sculptor Apollonius, son of Archias (found in Herculaneum, it is now in Naples). It is in this work that Polykleitos’s ideas about the ideal proportions of the human body, which are in numerical proportion to each other, are embodied. It was believed that the figure was created on the basis of the principles of Pythagoreanism, therefore in ancient times the statue of Doryphorus was often called the “canon of Polykleitos,” especially since the Canon was the name of his unpreserved treatise on aesthetics. Here the rhythmic composition is based on the principle of asymmetry (the right side, i.e. the supporting leg and the arm hanging along the body, are static, but charged with force, the left, i.e. the leg remaining behind and the arm with the spear, disturb the peace, but are somewhat relaxed ), which revives her and makes her mobile. The forms of this statue are extremely clear; they are repeated in most of the works of the sculptor and his school.

Commissioned by the priests of the Temple of Artemis of Ephesus c. 440 BC Polykleitos created a statue of a wounded Amazon, taking first place in a competition where, in addition to him, Phidias and Cresilaus participated. An idea of it is given by copies - a relief discovered in Ephesus, as well as statues in Berlin, Copenhagen and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Amazon's legs are set in the same way as Doryphoros's, but the free arm does not hang along the body, but is thrown behind the head; the other hand supports the body, leaning on the column. The pose is harmonious and balanced, but Polykleitos did not take into account the fact that if there is a wound under a person’s right chest, his right arm cannot be raised high up. Apparently, the beautiful, harmonious form interested him more than the plot or the transfer of feelings. The same care is imbued with the careful development of the folds of the short Amazon chiton.

Polykleitos then worked in Athens, where approx. 420 BC he created Diadumen, a young man with a bandage around his head. In this work, which was called a gentle youth, in contrast to the courageous Doryphoros, one can feel the influence of the Attic school. Here again the motif of a step is used, although both arms are raised and holding the bandage, a movement that would be better suited to a calm and steady position of the legs. The opposition between the right and left sides is not so pronounced. The facial features and voluminous curls of hair are much softer than in previous works. The best repetitions of Diadumen are a copy found at Delos and now in Athens, a statue from Vaison in France, which is kept in the British Museum, and copies in Madrid and in the Metropolitan Museum. Several terracotta and bronze figurines have also survived. The best copies of Diadumen's head are in Dresden and Kassel.

Around 420 BC. Polykleitos created a colossal chrysoelephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Hera seated on a throne for the temple in Argos. Argive coins may give some idea of what this ancient statue looked like. Next to Hera stood Hebe, sculptured by Naucis, a student of Polykleitos. In the plastic design of the temple one can feel both the influence of the masters of the Attic school and Polycletus; perhaps this is the work of his students. Polykleitos's creations lacked the majesty of Phidias's statues, but many critics consider them superior to Phidias in their academic perfection and ideal poise of posture. Polykleitos had numerous students and followers until the era of Lysippos (late 4th century BC), who said that his teacher in art was Doryphoros, although he later departed from Polykleitos’s canon and replaced it with his own.

4. Sculpture of Ancient Greece from the late classical era

The largest sculptors of the late classics are Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos, who in many ways anticipated the subsequent era of Hellenism.

4.1. Praxiteles

Praxiteles (IV century BC), ancient Greek sculptor, born in Athens c. 390 BC His works, mostly in marble, are known mainly from Roman copies and testimonies of ancient authors.

The best idea of the style of Praxiteles is given by the statue of Hermes with the baby Dionysus (Olympia, Archaeological Museum), which was found during excavations in the Temple of Hera at Olympia. Despite doubts that have been expressed, this is almost certainly an original, created c. 340 BC The flexible figure of Hermes gracefully leaned against the tree trunk. The master managed to improve the interpretation of the motif of a man with a child in his arms: the movements of both hands of Hermes are compositionally connected with the baby. Probably, in his right, unpreserved hand there was a bunch of grapes, with which he teased Dionysus, which is why the baby reached for it. The poses of the heroes moved even further away from the constrained straightness observed in earlier masters. The figure of Hermes is proportionally built and well-developed, the smiling face is full of liveliness, the profile is graceful, and the smooth surface of the skin contrasts sharply with the schematically outlined hair and the surface of the cloak thrown over the trunk. The hair, drapery, eyes and lips, and sandal straps were painted. Praxiteles considered the painting of statues to be an extremely important matter and entrusted it to famous artists, for example Nicias from Athens and others.

The masterful and innovative execution of Hermes has made it the most famous work of Praxiteles in modern times. However, in ancient times, his masterpieces were considered to be the statues of Aphrodite, Eros and satyrs that have not reached us. Judging by the surviving copies, they existed in several versions.

The statue of Aphrodite of Knidos was considered in ancient times not only the best creation of Praxiteles, but generally the best statue of all time. As Pliny the Elder writes, many came to Cnidus just to see her. It was the first monumental depiction of a fully nude female figure in Greek art, and was therefore rejected by the inhabitants of Kos, for whom it was intended, after which it was bought by the townspeople of neighboring Knidos. In Roman times, the image of this statue of Aphrodite was minted on Cnidian coins, and numerous copies were made from it (the best of them is now in the Vatican, and the best copy of the head of Aphrodite is in the Kaufmann collection in Berlin). In ancient times it was claimed that Praxiteles' model was his lover, the hetaera Phryne.