The history of the development of statues of ancient Egypt

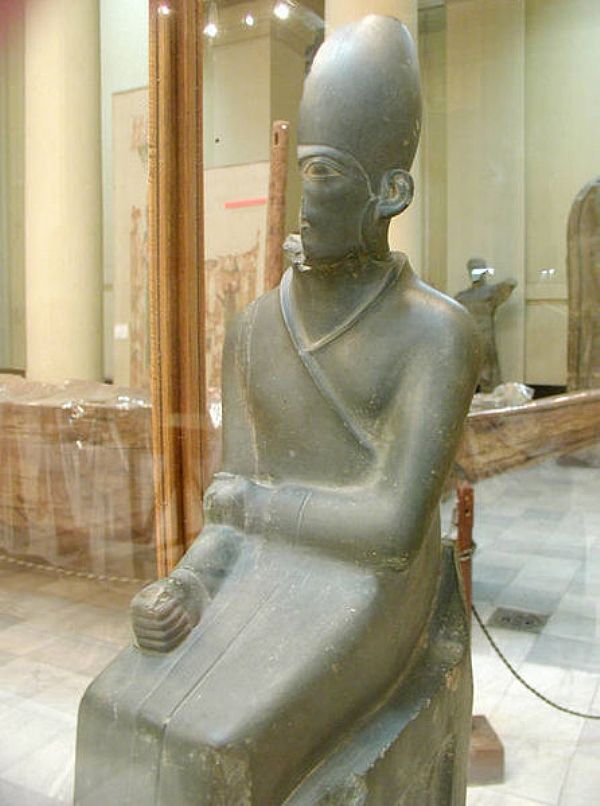

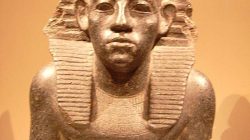

The tombs of the pharaohs, temple premises, and royal palaces were filled with various sculptures that formed an organic part of the buildings. The main images developed by sculptors were images of reigning pharaohs. Although the needs of the cult required the creation of images of numerous gods, the image of the deity, made according to rigid patterns, often with the heads of animals and birds, did not become central in Egyptian sculpture: in most cases it was a mass-produced and inexpressive product. Of much greater importance was the artistic development of the type of earthly ruler, his nobles, and, over time, ordinary people. From the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC. e. A certain canon has developed in the interpretation of the pharaoh: he was depicted sitting on a throne in a pose of dispassionate calm and grandeur, the master emphasized his enormous physical strength and size (powerful arms and legs, torso). During the Middle Kingdom, masters overcome the idea of cold grandeur and the faces of the pharaohs acquire individual features. For example, the statue of Senusret III with deep-set, slightly slanted eyes, a large nose, thick lips and protruding cheekbones quite realistically conveys an incredulous character, with a sad and even tragic expression on his face.

The masters felt more free when they portrayed nobles and especially commoners. Here the constraining influence of the canon is overcome, the image is developed more boldly and realistically, and its psychological characteristics are more fully conveyed. The art of individual portraiture, deep realism, and a sense of movement reached their peak during the New Kingdom, especially during the brief reign of Akhenaten (Amarna period). The sculptural images of the pharaoh himself, his wife Nefertiti, and members of his family are distinguished by their skillful conveyance of the inner world, deep psychologism, and high artistic skill.

In addition to round sculpture, the Egyptians willingly turned to relief. Many walls of tombs and temples, various buildings are covered with magnificent relief compositions, most often depicting nobles with their families, in front of the altar of the deity, among their fields, etc.

A certain canon was also developed in relief paintings: the main “hero” was depicted larger than others, his figure was depicted in a double plan: the head and legs in profile, the shoulders and chest in front. All figures were usually painted.

Along with reliefs, the walls of the tombs were covered with contour or pictorial paintings, the content of which was more varied than the reliefs. Quite often, these paintings depicted scenes of everyday life: artisans at work in the workshop, fishermen fishing, peasants plowing, street vendors with their goods, court proceedings, etc. The Egyptians achieved great skill in depicting wildlife - landscapes, animals, birds , where the restraining influence of ancient traditions was felt much less. A striking example is the painting of the tombs of the nomarchs discovered in Beni Hasan and dating back to the Middle Kingdom.

All ancient Egyptian art was subject to cult canons. Relief and sculpture were no exception here. The masters left outstanding sculptural monuments to their descendants: statues of gods and people, figures of animals.

The man was sculpted in a static but majestic pose, standing or sitting. In this case, the left leg was pushed forward, and the arms were either folded on the chest or pressed to the body.

Some sculptors were required to create figures of working people. At the same time, there was a strict canon for depicting a specific occupation - the choice of a moment characteristic of this particular type of work.

Among the ancient Egyptians, statues could not exist separately from religious buildings. They were first used to decorate the retinue of the deceased pharaoh and were placed in the tomb located in the pyramid. These were relatively small figures. When kings began to be buried near temples, the roads to these places were lined with many huge statues. They were so big that no one paid attention to the details of the image. The statues were placed near pylons, in courtyards and already had artistic significance.

During the Old Kingdom, the round form was established in Egyptian sculpture, and the main types of composition emerged. For example, the statue of Mikerinus depicts a standing man with his left leg extended and his arms pressed to his body. Or the statue of Rahotep and his wife Nofret represents a seated figure with his hands placed on his knees.

The Egyptians thought of the statue as the “body” of spirits and people. According to information from Egyptian texts, the god descended from the temple dedicated to him and was reunited with his sculptural image. And the Egyptians revered not the statue itself, but the embodiment of the invisible god in it.

Some statues were placed in temples in memory of “participation” in a certain ritual. Others were donated to temples in order to ensure the permanent patronage of the deity for the person depicted. Associated with prayers and appeals to the dead for the gift of offspring is the custom of bringing female figurines to the tombs of ancestors, often with a child in their arms or nearby (ill. 49). Small figurines of deities, usually reproducing the appearance of the main cult statue of the temple, were presented by believers with prayers for well-being and health. Images of women and ancestors were an amulet that promoted the birth of children, because it was believed that the spirits of ancestors could inhabit women of the clan and be reborn again.

The statues were also created for ka deceased. Because ka it was necessary to “recognize” exactly its own body and enter it, and the statue itself “replaced” the body, each face of the statue was endowed with a certain unique individuality (with the commonality of indisputable rules of composition). Thus, already in the era of the Old Kingdom, one of the achievements of ancient Egyptian art appeared - a sculptural portrait. This was facilitated by the practice of covering the faces of the dead with a layer of plaster - the creation of death masks.

![]()

Already in the era of the Old Kingdom, a narrow, closed room was built in the mastabas next to the prayer house ( serdab), in which a statue of the deceased was placed. At eye level of the statue there was a small window so that the one living in the statue ka the deceased could take part in funeral rites. It is believed that these statues served to preserve the earthly form of the deceased, as well as in case of loss or death of the mummy.

The spirit of the deceased endowed the statues with vitality, after which they “came to life” for eternal life. For this reason, we never see images of people, for example, in a pre-mortem or post-mortem form; on the contrary, there is exceptional vitality. The statues were made life-size, and the deceased was depicted exclusively as a young man.

In statues and reliefs, a person was always depicted as sighted, since the symbolism of the deceased’s “sighting” and his acquisition of vitality was associated with the eye. Moreover, the sculptor made the figures’ eyes especially large. They were always inlaid with colored stones, blue beads, faience, and rock crystal (ill. 50). For the eye for the Egyptians is the seat of the spirit and has a powerful influence on the living and on spirits

Since the life-giving power of the lotus, symbolizing magical revival, was “inhaled” through the nostrils, the human nose was usually depicted with an emphasized cut of the nostrils.

Since the lips of the mummy were endowed with the ability to pronounce the words of the afterlife confession, the lips themselves were never abstracted into a schematized sign.

In the creation of the type of sitting statues (with hands placed on their knees), statues of pharaohs made for the holiday played a large role heb-sed. His goal was the “revival” of an elderly or sick ruler, for there was a belief from the earliest times that the fertility of the earth was determined by the physical condition of the king. During the ritual, a statue of the ritually “killed” pharaoh was erected, and the ruler himself, “rejuvenated” again, performed a ritual beᴦ in front of the tent. Then the statue was buried and the coronation ceremony was repeated. After which it was believed that the ruler, full of strength, was again sitting on the throne.

Statues of the same person placed in tombs could be of different types, because they reflected various aspects of the funeral cult˸ one type conveyed the individual features of a person, without a wig, in fashionable clothes, the other had a more generalized interpretation of the face, was in an official apron and a fluffy wig.

The desire to ensure the “eternal” performance of the funeral cult led to the fact that statues of priests began to appear in tombs. The presence of figurines of children is also natural, since their indispensable duty was to take care of the funeral cult of their parents.

First hurt(they were discussed in question No. 2) date back to the 21st century. BC. If it was not possible to achieve a portrait resemblance between the ushabti and the deceased, the name and title of the owner whom it replaced was written on each figurine. Tools and bags were placed in the hands of the ushabti, and they were painted on their backs. Statues of scribes, overseers, and boatmen appear (ill. 51-a). For ushabti, baskets, hoes, hammers, jugs, etc. were made from faience or bronze. The number of ushabti in one tomb could reach several hundred. There were those who bought 360 pieces - one person for each day of the year. The poor bought one or two ushabtis, but along with them they put a list of three hundred and sixty such “helpers” in the coffin.

During some rituals, sculptures of bound prisoners were used. Οʜᴎ probably replaced living prisoners during the corresponding rituals (say, killing defeated enemies).

The Egyptians believed that the constant presence of sculptural images of participants in a religious ritual in the temple seemed to ensure the eternal performance of this ritual. For example, part of the sculptural group has been preserved, where the gods Horus and Thoth put a crown on the head of Ramesses III - this is how the coronation rite was reproduced, in which the roles of the gods were played by priests in appropriate masks. Its installation in the temple was supposed to contribute to the long reign of the king.

Found in tombs wooden the statues are associated with the funeral ritual (the repeated raising and lowering of the statue of the deceased as a symbol of the victory of Osiris over Set).

Statues of pharaohs were placed in sanctuaries and temples in order to place the pharaoh under the protection of the deity and at the same time glorify the ruler.

The giant colossal statues of the pharaohs embodied the most sacred aspect of the essence of the kings - their ka.

In the era of the Old Kingdom, canonical figures of the pharaoh appear standing with his left leg extended forward, in a short girdle and crown, sitting with a royal scarf on his head (ill. 53, 53-a), kneeling, with two vessels in his hands (ill. 54) , in the form of a sphinx, with the gods, with the queen (ill. 55).

In the eyes of the ancient Eastern people, the physical and mental health of the king was understood as a condition for the successful fulfillment of his function as a mediator between the world of people and the world of gods. Since the pharaoh for the Egyptians acted as the guarantee and embodiment of the “collective” well-being and prosperity of the country, he not only could not have flaws (which could also cause disasters), but also surpass mere mortals in physical strength. With the exception of the brief Amarna period, pharaohs have always been depicted as endowed with enormous physical strength.

The main requirement for the sculptor is to create the image of the pharaoh as the son of god. This determined the choice of artistic means. Despite the constant portraiture, there was a clear idealization of the appearance, developed muscles and a gaze directed into the distance were invariably present. The divinity of the pharaoh was complemented by details, for example, Khafre is guarded by a falcon, the sacred bird of the god Horus

The Amarna period was marked by a completely new approach to conveying the image of a person in sculpture and relief. The desire of the pharaoh to be different from the images of his predecessors - gods or kings - resulted in the fact that in the sculpture he appeared, it is believed, without any embellishment on a skinny, folded neck - an elongated face, with drooping half-open lips, a long nose, half-closed eyes, puffy belly, thin ankles with full hips

Statues of private individuals.

The Egyptians have always imitated official sculpture - images of pharaohs and gods, strong, strict, calm and majestic. The sculptures never express anger, surprise, or smile. The spread of statues of private individuals was facilitated by the fact that nobles began to build their own tombs.

The statues were of different sizes - from several meters to very small figures of several centimeters.

Sculptors, sculpting private individuals, were also obliged to adhere to the canon, primarily frontality and symmetry in the construction of the figure (ill. 60, 61). All statues have the same straight head, and almost the same attributes in their hands.

During the era of the Old Kingdom, sculptural statues of married couples with children appeared (ill. 62, 63), scribes sitting cross-legged, with an unrolled papyrus scroll on their knees - at first only royal sons were depicted this way

Temple of Horus in Edfu

Material and processing.

Already in the Old Kingdom there were sculptures made of red and black granite, diorite, quartzite (ill. 68), alabaster, slate, limestone, and sandstone. The Egyptians loved hard rocks.

Images of gods, pharaohs, and nobles were made mainly of stone (granite, limestone, quartzite). It is worth saying that for small figurines of people and animals, bone and faience were most often used. Servant statues were made of wood. Ushabti were made of wood, stone, glazed faience, bronze, clay, and wax. Only two ancient Egyptian copper sculptures are known.

Inlaid eyes with contoured relief rims of the eyelids are characteristic of statues made of limestone, metal or wood.

The limestone and wood sculptures were originally painted.

Late Egyptian sculptors began to prefer granite and basalt to limestone and sandstone. But bronze became the favorite material. Images of gods and figurines of animals dedicated to them were made from it. Some were made up of separately manufactured parts; the cheap ones were cast in clay or plaster molds. Most of these figurines were made using the “lost wax” technique, widespread in Egypt; the sculptor made a blank of the future image from clay, covered it with a layer of wax, worked out the intended shape, coated it with clay and put it in the oven. The wax flowed out through a specially left hole, and liquid metal was poured into the resulting void. When the bronze cooled, the clay mold was broken and the product was removed, and its surface was carefully processed and then polished. For each product, its own form was created and the product turned out to be unique.

Bronze items were usually decorated with engraving and inlays. For the latter, thin gold and silver wires were used. Gold stripes were used to outline the eyes of the ibis, and necklaces made of gold threads were placed on the necks of bronze cats.

The famous ancient Egyptian colossal statues are of interest from the point of view of the complexity of processing solid materials.

On the west bank of the Nile, opposite Luxor, there are two statues dating from the New Kingdom, called the “colossi of Memnon”. According to one version of Egyptologists, the Greek name Memnom comes from one of the names of Amenhotep III. According to another version, after the earthquake on 27 ᴦ. BC. one of the statues was significantly damaged, and, probably due to differences in night and day temperatures, the cracked stone began to make continuous sounds. This began to attract pilgrims who believed that in this way the Ethiopian king Memnon, a character in Homer’s Iliad, greeted the goddess of the dawn Eos, his mother.

At the same time, there are no intelligible explanations of how colossi made of quartzite, 20-21 meters high, each weighing 750 tons, were placed on a pedestal also made of quartzite weighing 500 tons manually, can not found. Moreover, it was still necessary to deliver stone monoliths (or parts thereof?) 960 kilometers away up along the Nile.

Sculpture from the Early Dynastic period comes mainly from three large centers where the temples were located - Ona, Abydos and Koptos. The statues served as objects of worship, rituals and had a dedicatory purpose. A large group of monuments was associated with the “heb-sed” ritual - a ritual of renewing the physical power of the pharaoh. This type includes the types of sitting and walking figures of the king, executed in round sculpture and relief, as well as the image of his ritual running. The list of Kheb-sed monuments includes a statue of Pharaoh Khasekhem, represented seated on a throne in ritual attire. This sculpture indicates an improvement in technical techniques: the figure has correct proportions and is volumetrically modeled. The main features of the style have already been identified here - monumental form, frontal composition. The pose of the statue is motionless, fitting into the rectangular block of the throne; straight lines predominate in the outlines of the figure. Khasekhem's face is portrait-like, although his features are largely idealized. The placement of the eyes in the orbit with a convex eyeball is noteworthy. A similar technique of execution extended to the entire group of monuments of that time, being a characteristic stylistic feature of portraits of the Early Kingdom. By this same period, the canonicity of the pre-dynastic period standing at full height was established, giving way in the plastic arts of the Early Kingdom to the correct rendering of the proportions of the human body.

Old Kingdom Sculpture

Significant changes in sculpture occur precisely in the Middle Kingdom, which is largely explained by the presence and creative competition of many local schools that gained independence during the period of collapse. Since the time of the XII Dynasty, ritual statues have become more widely used (and, accordingly, produced in large quantities): they are now installed not only in tombs, but also in temples. Among them, images associated with the rite of heb-sed (ritual revival of the pharaoh's life force) still dominate. The first stage of the ritual was associated with the symbolic murder of the elderly ruler and was performed over his statue, which in composition resembled canonical images and sculptures of sarcophagi. This type includes the gray-haired statue of Mentuhotep-Nebkhepetra, depicting the pharaoh in a pointedly frozen pose with his arms crossed on his chest. The style is distinguished by a large share of conventionality and generality, generally typical for sculptural monuments of the early era. Subsequently, the sculpture comes to a more subtle modeling of faces and greater plastic dismemberment: first of all, this is manifested in female portraits and images of private individuals.

Over time, the iconography of the kings also changes. By the time of the 12th Dynasty, the idea of the divine power of the pharaoh gives way in images to persistent attempts to convey human individuality. The heyday of sculpture with official themes occurred during the reign of Senwosret III, who was depicted at all ages - from childhood to adulthood. The best of these images are considered to be the obsidian head of Senusret III and sculpted portraits of his son Amenemhat III. The type of cubic statue - an image of a figure enclosed in a monolithic stone block - can be considered an original find by masters of local schools.

The art of the Middle Kingdom is the era of the heyday of the plastic arts of small forms, mostly still associated with the funeral cult and its rituals (sailing on a boat, bringing sacrificial gifts, etc.). The figurines were carved from wood, covered with primer and painted. Entire multi-figure compositions were often created in round sculpture (similar to how it was customary in the reliefs of the Old Kingdom

New Kingdom sculpture

In the art of the New Kingdom, a sculptural group portrait appears, especially images of a married couple.

The art of relief acquires new qualities. This artistic field is noticeably influenced by certain genres of literature that became widespread during the New Kingdom: hymns, war chronicles, love lyrics. Often texts in these genres are combined with relief compositions in temples and tombs. In the reliefs of Theban temples there is an increase in decorativeness, free variation of bas-relief and high-relief techniques in combination with colorful paintings. This is the portrait of Amenhotep III from the tomb of Khaemkhet, which combines different heights of relief and in this regard is an innovative work. Reliefs are still arranged according to registers, allowing the creation of narrative cycles of enormous spatial extent

Wooden sculpture of one of the Egyptian gods with the head of a ram

Late Kingdom sculpture

During the time of Kush, in the field of sculpture, the skills of ancient high craftsmanship partly fade away - for example, portrait images on funeral masks and statues are often replaced by conditionally idealized ones. At the same time, the technical skill of sculptors is improving, manifesting itself mainly in the decorative field. One of the best portrait works is the head of the statue of Mentuemhet, made in a realistic and authentic manner.

During the period of Sais's reign, staticity, conventional outlines of faces, canonical poses, and even the semblance of an “archaic smile”, characteristic of the art of the Early and Old Kingdoms, again became relevant in sculpture. However, the masters of Sais interpret these techniques only as a theme for stylization. At the same time, Sais art produces many wonderful portraits. In some of them, deliberately archaic forms imitating ancient rules are combined with rather bold deviations from the canon. Thus, in the statue of the close associate of Pharaoh Psametikh I, the canon of a symmetrical image of a seated figure is observed, but, in violation of it, the left leg of the seated person is placed vertically. In the same way, canonically static body shapes and the modern style of depicting faces are freely combined.

In the few monuments from the era of Persian rule, purely Egyptian stylistic features also predominate. Even the Persian king Darius is depicted on the relief in the garb of an Egyptian warrior with sacrificial gifts, and his name is written in hieroglyphs.

The majority of sculptures of the Ptolemaic period are also made in the traditions of the Egyptian canon. However, Hellenistic culture influenced the nature of the interpretation of the face, introducing greater plasticity, softness and lyricism.

Ancient Egypt. Male head from the Salt collection. First half of 3 thousand BC.

Figurine of the porter Meir. Tomb of Niankhpepi. VI dynasty, reign of Peggy II (2235-2141 BC). Cairo Museum

PEASANT WITH A HOE. For excavation work, a hoe was used, which was originally wooden, then metal ones appeared, consisting of two parts: a handle and a lever.

Three bearers of sacrificial gifts. Wood, painting; height 59 cm; length 56 cm; Meir, tomb of Niankhpepi the Black; excavations by the Egyptian Antiquities Service (1894); VI dynasty, reign of Pepi I (2289-2255 BC).

Scientists still have not determined when exactly the oldest statue in the world, the sculpture of the Sphinx, was erected: some believe that the world saw this grandiose structure back in the thirtieth century BC. But most researchers are still more cautious in their assumptions and claim that the Sphinx is no more than fifteen thousand years old.

This means that already at the time of the creation of the most grandiose monument of mankind (the height of the Sphinx exceeded twenty meters and the length - more than seventy), art, in particular sculpture, was already well developed in Egypt. It turns out that in reality it is much older than the Egyptian culture, which appeared in the 4th millennium BC.

Most researchers question this version and so far agree that the face of the Sphinx is the face of Pharaoh Hebren, who lived around 2575 - 2465. BC e. - which means it indicates that this grandiose structure from monolithic limestone rock was carved by the Egyptians. And he guards the pyramids of the pharaohs in Giza.

Almost all researchers agree that the funeral cult of the inhabitants of ancient Egypt played an important role in the development of sculpture - if only because they were convinced: the human soul could well return to earth to its body, a mummy (it was for this purpose that huge tombs were created, structures in which the deceased bodies of pharaohs and nobles were supposed to be located). If the mummy could not be preserved, it could well move into its likeness - a statue (which is why the ancient Egyptians called the sculptor “creator of life”).

They created this life according to once and for all established canons, from which they did not deviate for several millennia (special instructions and guidelines were even provided and developed specifically for this purpose). Ancient masters used special templates, stencils and grids with canonically established proportions and contours of people and animals.

The sculptor’s work consisted of several stages:

- Before starting to work on the statue, the master chose a suitable stone, usually rectangular in shape;

- After that, using a stencil, I applied the desired design to it;

- Then, using the carving method, I removed the excess stone, after which I processed the details, grinded and polished the sculpture.

Characteristics of Egyptian sculptures

Mostly ancient Egyptian statues depicted rulers and nobles. The figure of a working scribe was also popular (he was usually depicted with a roll of papyrus on his lap). Sculptures of gods and rulers were usually displayed for public viewing in open spaces.

The statue of the Sphinx was especially popular - despite the fact that structures of the same size as in Giza had never been made anywhere else, there were many smaller duplicates of it. Alleys with its copies and other mystical beasts could be seen in almost all the temples of ancient Egypt.

Considering that the Egyptians considered the pharaoh to be the incarnation of god on earth, the sculptors emphasized the greatness and indestructibility of their rulers with special techniques - the arrangement of figures and scenes, their sizes, poses and gestures (poses intended to convey any moment or mood were not allowed).

The ancient Egyptians depicted gods only according to strictly defined rules (for example, Horus had the head of a falcon, while the god of the dead, Anubis, had a jackal). The poses of the human statues (both sitting and standing) were quite monotonous and the same. All seated figures were characterized by the pose of Pharaoh Khafre sitting on the throne. The figure is majestic and static, the ruler looks at the world without any emotions and it is obvious to anyone who sees him that nothing can shake his power, and the character of the pharaoh is imperious and unyielding.

If the sculpture depicting a man is standing, his left leg always takes a step forward, his arms are either lowered down, or he is leaning on the staff he is holding. After some time, another pose was added for men - the “scribe”, a man in the lotus position.

At first, only the sons of the pharaohs were depicted this way. The woman stands straight, legs are closed, right hand is lowered, left hand is on the waist. Interestingly, she does not have a neck; her head is simply connected to her shoulders. Also, the craftsmen almost never drilled out the spaces between her arms, body and legs - they usually marked them in black or white.

The masters usually made the bodies of the statues powerful and well-developed, giving the sculpture solemnity and grandeur. As for faces, portrait features are, of course, present here. When working on the statue, the sculptors discarded minor details and gave the faces an impassive expression.

The coloring of ancient Egyptian statues also did not differ in particular variety:

- male figures were painted red-brown,

- women's - yellow,

- hair – black;

- clothes - white;

The Egyptians had a special relationship with the eyes of sculptures - they believed that the dead could observe earthly life through them. Therefore, masters usually inserted precious or other materials into the eyes of statues. This technique allowed them to achieve greater expressiveness and even liven them up a little.

Egyptian statues (this does not mean fundamental structures, but smaller products) were not designed to be viewed from all sides - they were completely frontal, many of them seemed to lean back against a stone block, which served as a background for them.

Egyptian sculptures are characterized by complete symmetry - the right and left halves of the body are absolutely identical. Almost all the statues of ancient Egypt have a sense of geometricity - this is most likely explained by the fact that they were made from rectangular stone.

The evolution of Egyptian sculptures

Since creativity cannot help but respond to changes that occur in the life of society, Egyptian art did not stand still and over time changed somewhat - and began to be intended not only for funeral rites, but also for other buildings - temples, palaces, etc.

If at first they depicted only gods (a large statue of one or another deity made of precious metals was located in the temple dedicated to him, in the altar), sphinxes, rulers and nobles, then later they began to depict ordinary Egyptians. Such figurines were mostly wooden.

Many small figurines made of wood and alabaster have survived to this day - and among them there were figurines of animals, sphinxes, slaves, and even property (many of them subsequently accompanied the dead to the other world).

Early Kingdom statues (IV millennium BC)

Sculpture during this period developed mainly in the three largest cities of Egypt - Ona, Kyptos and Abydos: it was here that there were temples with statues of gods, sphinxes, and mystical animals that the Egyptians worshiped. Most of the sculptures were associated with the ritual of renewing the physical power of the ruler (“heb-sed”) - these are, first of all, figures of sitting or walking pharaohs carved into the wall or presented in a round sculpture.

A striking example of this type of statue is the sculpture of Pharaoh Khasekhem, sitting on a pedestal, dressed in ritual clothing. Already here you can see the main features of ancient Egyptian culture - correct proportions, in which straight lines and monumental form predominate. Despite the fact that his face has individual facial features, they are overly idealized, and his eyes have the convex eyeball traditional for all sculptures of that era.

At this time, canonicity and conciseness are established in the form of expression - secondary signs are discarded and attention is focused on the majesty in the image.

Statues of the Ancient Kingdom (XXX – XXIII centuries BC)

All statues of this period continue to be made according to previously established canons. It cannot be said that preference is given to any particular pose (this is especially true for male figures) - both full-length statues with the left leg extended forward, as well as those seated on a throne, sitting with legs crossed in the shape of a lotus, or kneeling, are popular.

At the same time, precious or semi-precious stones began to be inserted into the eyes, and raised eyeliner was applied. Moreover, the statues began to be decorated with jewelry, thanks to which they began to acquire individual features (examples of such works are the sculptural portraits of the architect Rahotep and his wife Nofret).

At this time, wooden sculpture was significantly improved (for example, the figure known as the “Village Headman”), and in the tombs of those times you can often see figurines that depict working people.

Statues of the Middle Kingdom (XXI–XVII centuries BC)

During the Middle Kingdom in Egypt, there were a huge number of different schools - accordingly, the development of sculpture underwent significant changes. They are beginning to be made not only for tombs, but also for temples. At this time, the so-called cubic statue appeared, which is a figure enclosed in a monolithic stone. Wooden statues are still popular, which the craftsmen, after carving from wood, covered with primer and painted.

Sculptors are increasingly paying attention to the individual characteristics of a person - with the help of perfectly crafted elements, in their works they show the character of a person, his age and even his mood (for example, just by looking at the head of Pharaoh Senusret III, it becomes clear that he was once a strong-willed , imperious, ironic ruler).

Statues of the New Kingdom (XVI–XIV centuries BC)

During the New Kingdom period, monumental sculpture received special development. Not only does it increasingly go beyond the boundaries of the funerary cult, but it also begins to show individual features that are not typical not only of official, but even of secular sculpture.

And secular sculpture, especially when it comes to the female figure, acquires softness, plasticity, and becomes more intimate. If earlier, according to the canons, female pharaohs were often depicted in full royal garb and even with a beard, now they get rid of these features and become elegant, graceful, and refined.

Amarna period (beginning of the 14th century BC)

At this time, sculptors began to abandon the highly idealized, sacred image of the pharaoh. For example, using the example of the huge statues of Amenhotep IV, you can see not only traditional techniques, but also an attempt to convey as accurately as possible the appearance of the pharaoh (both his face and figure).

Another innovation was the depiction of figures in profile (previously the canon did not allow this). During this period, the world-famous head of Nefertiti in a blue tiara, created by sculptors from the Thutmes workshop, also appeared.

Late Kingdom Statues (XI – 332 BC)

At this time, masters begin to adhere less and less to the canons, and they gradually fade away and become conditionally idealized. Instead, They began to improve their technical skills, especially in the decorative part (for example, one of the best sculptures of that time is the head of the statue of Mentuemhet, made in a realistic style).

When Sais was in power, the masters again returned to monumentality, staticity and canonical poses, but they interpreted this in their own way and their statues became more stylized.

After in 332 BC. Alexander the Great conquered Egypt, this country lost its independence, and the cultural heritage of ancient Egypt finally and irrevocably merged with ancient culture.

The bestial grin of the Paleolithic

Archaeologists have made the ancient statue the oldest

Photo Stadt Ulm Ulmer Museum

The Lion Man, a thirty-centimeter figurine made of mammoth bone, found on the eve of World War II in southern Germany, was sculpted 40 thousand years ago. New dating has made the unprecedented work of art, stored in the German city of Ulm, older by 8 thousand years. It took scientists more than 70 years to literally piece together this amazing figurine. The latest calculations show that the Paleolithic artist spent at least 400 hours on the Lion Man - about two months of work during daylight hours.

The message about the new dating of the lion man appeared on the eve of the opening of a large exhibition on Paleolithic art at the British Museum. The Ulm sculpture was to adorn the exhibition along with such works of ancient art as the Trans-Raisian bison and the Vestonitsa Venus. However, the restorers did not consider it possible to transport the lion man to London: he is too fragile. A copy of the priceless sculpture has been sent to the UK.

The Lion Man was found in southern Germany, in an area known as the Swabian Jura or Swabian Alb. In the low chalk mountains there there are several caves, four of which - Vogelherd, Stadel, Geissenklosterle and Hole Fels - became famous due to the oldest images of animals and birds, the first musical instruments (flutes) and the first images of humans discovered in them. Most of the finds now date back 35,000 to 40,000 years, including the Venus of Hohle Fels (an anthropomorphic figure with raised arms) and a intact mammoth figurine. The time of making flutes has been pushed back even further - to 42-43 thousand years. Paul Mellars, one of the leading modern researchers of the Paleolithic of Europe, commenting several years ago on the discovery of the Venus of Hole Fels, said that the southern German caves should rightfully be considered the birthplace of European sculpture.

The honor of discovering the lion man belongs to the German archaeologist Robert Wetzel, who explored the Stadel cave. Wetzel had been conducting systematic excavations in the cave since 1937; before him, dozens, if not hundreds of enthusiasts had been there, looking for traces of the presence of primitive people in it, because even in the middle of the 19th century, bones of cave animals and stone tools were found there. Wetzel, an employee of the Ulm Museum, discovered fragments of a bone figurine a few days before the outbreak of World War II - on August 25, 1939. The fragments were removed from the ground, packed in a box and sent to the University of Tübingen, where they waited in the wings for thirty years. Wetzel's excavation was filled up and securely covered. The professor returned to study the cave in 1954 and worked in it every season until his death in 1961. But he didn’t remember the bone figurine.

In 1969, during an inventory of the storage rooms of the Ulm Museum, a box containing fragments of the lion man was finally discovered. The fragments were taken out, a “draft” figurine was assembled from two hundred fragments (two hundred fragments made up approximately 70 percent of the volume), radiocarbon dated and a sensational age was obtained: 32 thousand years. Until then, the oldest sculpture was considered to be the above-mentioned Vestonice Venus (25-29 thousand years old), found in Moravia.

The first researcher of the lion man was the outstanding archaeologist from the University of Tübingen, Joachim Hahn, a specialist in the Upper Paleolithic and an expert in the primitive art of Europe. Thanks to Khan's reconstruction, it became clear that the figurine has both anthropomorphic and zoomorphic features, and the animal component came from a large cat. Khan was unable to find virtually any fragments of the head, and his reconstruction of the figurine included male genitalia.

Khan's younger colleague Elisabeth Schmid took up the Lion Man in the early 1980s. By this time, during new excavations, several hundred more fragments of the sculpture had been discovered, and Schmid was able to significantly complement the appearance of the man-beast - in particular, its lion's muzzle became clearly visible. It is worth noting that before completing the appearance of the lion man, Schmid took the figurine apart, removing the glue that Khan used, and reassembled it. Schmid came to the conclusion that the man-cat creature was not a man, but a woman, and the lion man temporarily turned into a lioness man, becoming the banner of supporters of the matriarchal model of Upper Paleolithic society.

By 2000, passions over the gender of the sculpture had fortunately subsided. And in 2009, another archaeologist from the University of Tübingen, Claus-Joachim Kind, went to the Stadel cave to complete the search for fragments. Kind found several important fragments of the back and neck, the right arm and paw, and hundreds of small fragments, so that by the end of 2012 the “three-dimensional puzzle” was completed. Alas, many elements of the “puzzle” are lost forever: in particular, it is not clear what exactly the hands and feet of the lion man looked like, whether he had a tail, and so on.

Researchers have countless questions for the lion man. Who is this creature - a deity or a guide from one world to another? We don’t know anything about the ideas of the creators of the figurine about the world - we only assume, using analogies with the primitive societies known to us, where the most important role is played by shamans, guides from the world of the living to the worlds of animals and the dead. Or maybe everything is simpler, and the lion man is the ideal male? (Every joke has a grain of humor in it.) Why was it sculpted - to be worshiped or carried with you as an amulet? And these are only the most obvious assumptions - from our point of view, infinitely removed from the worldview of the inhabitants of the Stadel cave.

What do the notches on the left shoulder of the figurine mean? Is there some connection between the lion man and the anthropomorphic figure from Geissenklosterle, who also has marks on his hands? Let us remind you that Geissenklosterle is one of the four most famous caves in the Swabian Alb, along with Stadel. Excavations there were carried out by Joachim Hahn, already known to us, and he found a plate on which a relief human (or bestial-human) figure with raised arms is depicted. Chronologically, she is a contemporary of the Leo Man. Some interpreters call her an “adorant,” that is, one who worships a deity, a higher power; It is believed that the record depicts a shamanic dance.

Why is the lion man large - almost 30 centimeters, while most other bone figurines do not exceed seven centimeters in height? The “adorant” is less than four centimeters high, the height of “Venus from Hole Fels” is six centimeters.

More general questions also arise: what led 40-45 thousand years ago to such an explosion of plastic art, not only in the Swabian Alb, but also in other regions of Europe - in the territory of modern France, Spain and Italy? Is the emergence of art connected with the development of language or with the influx of new populations?

Whether it is possible in principle to find answers to these questions is a separate problem. But we can be glad that at least something tangible has survived from those distant times. Wild but cute.