Outstanding sculptors of ancient Greece message. Stages of development of ancient Greek sculpture: Stages of development of ancient Greek sculpture. Convey the feelings and experiences of a person

St. Petersburg State University of Economics and Management

COURSE WORK

By discipline"Culturology"

On the topic « Outstanding sculptors Ancient Greece»

Completed by a student

Soyuzova Maria

Feodosia

INTRODUCTION 3

CHAPTER 1. THE ORIGIN OF ANCIENT SCULPTURE

ANCIENT GREECE 4

Originally made for the real St. Patrick's College in Lisbon, where he formed the Irish clergy for missionary work in the first half of this year and preceding the public opening of the sculpture gallery, it received restoration work from the conservative Conceição Ribeiro.

The best of diary news in your email

Despite the fact that the situation is "serious", and noting that there is still a diagnosis by the technical team, José Alberto Sibra Carvalho is confident, given that "from a technical point of view it will be a labor-intensive, but not very difficult, restoration." The fact that it is made of wood and consists of several parts are factors that point to the role of mediators of the Conservative mission. "And it won't be on display again anytime soon," he says. Perhaps this should be open. After the incident, “we will need to take some action,” the official said.

1.1. Period from 900 to 575 BC. 4

1.2. Period from 575 to 475 BC. 5

CHAPTER 2. OUTSTANDING SCULPTORS OF THE ERA

ARCHAIC 6

CHAPTER 3. OUTSTANDING SCULPTORS OF THE ERA

CLASSICS 9

3.1. Myron from Eleuther 9

3.2. The greatest Phidias and Polykleitos 10

3.3. Representatives late classic(Praxitel,

Scopas and Lysippos) 14

The piece "was secured to a plinth, and we have to think of another way to secure it to a plinth, or even to a different plinth." The official statement from the Ministry of Culture about this incident goes in the same direction: In the coming days and after the incident is reported, the Directorate General of Cultural Heritage will assess in detail the damage and the need to change the museum exhibition in order to prevent accidents.

The situation occurred on Sunday, the first month and, as such, free entry. José Alberto Seabra de Carvalho believes that "it is a little insulting to do this relationship." I have no information about the flood in the museum on this Sunday, the first Sunday of every month usually has twice the number of visitors compared to other Sundays, and in this particular room, when there is a large turnout, entrances are conditional, he explains.

CHAPTER 4. SCULPTORS OF THE HELLENISM ERA 20

CONCLUSION 22

LIST OF SOURCES USED 23

INTRODUCTION

The subject of this essay is the outstanding sculptors of Ancient Greece. In my opinion, this topic is one of the most important in the study of ancient Greek civilization, since sculpture, like all fine arts in general, reflects the entire life and entire history of the nation.

Among the museums directly under the Ministry of Culture, ancient art is the second most visited in the country. While acknowledging the lack of vigilance in the museum - less than thirty for the 82 rooms open to the public, the deputy director also clarifies that when the exuberance is too much, the museum's preventative measure is to close some rooms. It's bad that the rooms are closed to the public, but we are following this safer route.

Absolute certainty that one of these days there is a disaster in the museum. This can only be because we are playing property. But for now, all the guardians have all the information that will happen, but when it happens, it opens news channels, said Antonio Filipe Pimentel, who was quoted by Luza.

http://historic.ru/lostcivil/greece/gallery/stat_003.shtml Faced with Greek sculpture of the ancient period, many outstanding minds expressed genuine admiration. One of the most famous researchers of the art of ancient Greece, Johann Winckelmann (1717-1768) spoke about Greek sculpture: “Connoisseurs and imitators of Greek works find in their masterful creations not only the most beautiful nature, but also more than nature, namely its certain ideal beauty, which... is created from images sketched by the mind.” And the aged Goethe sobbed in the Louvre in front of the sculpture of Aphrodite. Everyone who has written and is writing about Greek sculpture of the ancient period notes in it an amazing combination of naive spontaneity and depth, reality and fiction. It embodies the ideal of man.

However, even in its specific meaning, the statue of worship was meant to represent a specific form of Ersteinung, capable of expressing and representing the best qualities of the divine figure, starting from the latter's "common and common idea" and through a language that primarily refers to anthropomorphic representation.

Based on the classical belief that gods have the same nature as men, anthropomorphism seems to be a Greek solution, already corresponding to the mycological Miocene world and later inherited from the Roman, for representing the gods. it is widely emphasized that among the artistic civilizations of antiquity, the Greek, more than any other, "the problem of the statue as a representation of the human figure is solved and solved in complete autonomy." Consequently, the frequent choice of comprehensive sculpture, which is most effective and suitable for the anthropomorphic rendering of the divine figure, and therefore for images of worship, in the face of the rarest, although significant, use of relief in the context of some popular and domestic cults and others not Greek origin.

The Greeks always believed that only in a beautiful body can a beautiful soul live. Therefore, harmony of the body and external perfection are an indispensable condition and the basis of an ideal person. The Greek ideal is defined by the term kalokagathia (Greek kalos - beautiful + agathos good). Since kalokagathia includes the perfection of both physical constitution and spiritual and moral makeup, then at the same time, along with beauty and strength, the ideal carries justice, chastity, courage and rationality.

Although from the point of view of an exclusively historical and artistic point of view, the production of cult images is, as is natural, part of the stylistic and formal developments greek sculpture However, because of its specific function and its deep religious significance, as well as for its formal conservatism, it should be understood as a special phenomenon of the Greek artistic experience, which in fact represented the Greeks as a fundamental element of religious practice. In the creation myth invoked by Protagoras in Plato, the erection of altars and images of deities is even considered one of the first actions of people.

Greek sculpture spread far beyond the borders of its homeland - to Asia Minor and Italy, to Sicily and other islands of the Mediterranean, to North Africa and other places where the Greeks founded their settlements. Greek cities were even on the northern coast of the Black Sea.

Nowhere else has sculpture risen to such a height—nowhere else has a person been so valued as in ancient Greek civilization. The creations of the sculptors of Ancient (Ancient) Greece are the ideal, the canon for the art of many later civilizations. It does not lose its relevance even today, when new types of art are being formed, and general views on art are repeatedly revised and changed.

In general, for the Greeks of old age, a cult without images is unthinkable, and those peoples who do not have statues of deities are strange. Although very rare, there are, however, famous shrines in Greece, mainly dedicated to Zeus, devoid of cult images; a phenomenon according to which it is likely that, like all other literary sources, suppose, especially religious beliefs and religious practices, for which the perception of the presence of divinity does not require figurative means. For this connection, it is assumed that Greek religious thought was influenced by models from the Near Eastern region.

CHAPTER 1. THE ORIGIN OF ANCIENT SCULPTURE IN ANCIENT GREECE

1.1. Period from 900 to 575 BC.

The beginnings of Greek sculpture were very insignificant. Corresponding to the earliest Boeotian style of vases are the remarkable clay female figurines found in Boeotian tombs; their bell-like shape is determined by their clothing, which lags behind the body. The excessively long neck, small head, lack of mouth, sharp profile and ornamental pattern are reminiscent of the primitive style of Europe. Several figurines of naked women kept in the Athens Museum, made of ivory, in the proportions of the body of which, with all their geometric angularity, a significant step forward is already noticeable, were found in Attic Dipylonian tombs.

The introduction of the "mode of worship" and, together, the definition of the form and function of the Greek temple was supposed to be a break with the past, and it was a phenomenon that more or less simultaneously included the entire Greek world, with obvious consequences on the plane of religious ideology that was slowly taking shape at the time . Gradually the two religious elements, the statue and the temple, became the emblem of Greek Ploas, the expression of its identity, the true manifestation of its power and its prestige. Homeric poetry seems to know the temple as the abode of the deity and his statue as the recipient of worship.

The beginnings of the sculpting of large figures among the Greeks, just like the beginnings of their architecture, must be sought in the production of wood. Numerous wooden idols (xoans), considered to have fallen from the sky, reminded the later Hellenes of the initial time of their sculpture. Not a single one of these wooden figures has reached us, but many sculptures made of loose limestone (poros) or coarse-grained island marble have survived. More or less well-preserved works of this kind were obtained mainly from the remains of structures destroyed by the Persians in the Athenian Acropolis, as well as on Delos and its neighboring islands. The male statues depict young, beardless, naked people; female statues in clothes.

In Athena Ilio it is recognized not so much by the goddess of the Mycenaean palace as by the divine state which has its temple, its image of worship, in this case a seated statue and its priestess. For this reason, its specific character, connected with the rest of its function, was that of a type of statue imbued with a special holiness, which, in the case of some old images, was sometimes enhanced by the memory of their legendary or divine origin; connections with the characters of the myth, and in some cases, “given” by Daedalo.

Think, in addition to the famous Palladio Ilio, who miraculously fell from the sky, like other famous ones. and an incomparably precious and mysterious object, even for the mythical statue of Artemis, which Iphigenia took from Tauris and with which several shrines in Greece identified their ancient cultic simulacrum. In this case, like Athena Polias, protective qualities were attributed, while in other cases even miraculous properties were recalled. Such qualities contributed to the sanctification of statues for worship, as well as the practice of prohibiting the views of believers or, in some cases, even binding them.

In contrast to all these stone sculptures, which echo the wooden style, the seated statues from Didymaeon, famous temple The life-size statues of Apollo at Didyma, near Miletus, bear the imprint of the primitive Asian stone style. In terms of their size, position and inscriptions, these portrait statues are from the first quarter of the 7th century. They appear to be the most ancient works of Ionic monumental sculpture.

The theme and center of cultural action, these images were intended by believers for sacrifices, offerings, prayers and various devotions. A series of literary and epigraphic evidence recalled that some archaic representations also directly and physically participated in certain rituals, such as processions, purification baths, nutrition and clothing. C were ceremonies during which, on a certain day, the image of the divinity was removed from its temple and placed elsewhere to be seen and worshiped by the faithful.

The branch of Dionysus Eleutheres in Athens, which was removed from its temple and sent to yoga at the Academy on the eve of the Great Dionysus. Vascular configurations showing statues of deities placed on columns or bases at the altar most likely reflect such a practice, which aimed to place the image of worship in more direct relation to the sacrificial act.

We have seen how Greek art in all its branches, under Eastern, mainly Western Asian, and also Egyptian influence, emerged from its original rough state and developed a national, independent style, in which a careful, albeit timid observation of nature was combined with the strictest regularity.

As is well known, there is a precise term in the Greek dictionary that only refers to a statue of worship. Among the ancient authors who recall or even depict images of worship, Pausania is without a doubt the most reliable and rich in information, especially regarding the most ancient cultural sculpture, in general, referring to the name of the artist, tales and myths relating to the statue, the material in which it is made, its installation and, in some cases, its dimensions and attributes.

On the other hand, archaeological direct evidence for statue worship is few and weak. The use of perishable or particularly valuable materials often prevented the survival of such operas. Additionally, recognizing the cultural function of a statue is often difficult due to the lack of reliable information surrounding its location and its original placement or clues. The same cultural context does not always allow one to differentiate between worship statues and worship statues. The colossal size of the statue is not in itself a definite element of distinction, since already in archaic times religious statues of deities larger than natural ones were dedicated to votive statues.

1.2. Period from 575 to 475 BC.

Among the sculptors of this era we meet Royka and Theodore of Samos. Royk owned a bronze female figure, probably called “Night” and standing in Ephesus, near the Temple of Artemis. From the works of Theodore, mainly gold items are known, for example, a ring made for Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, and a silver mixing vessel.

However, votive statues and images of worship can sometimes share the same typology and iconographic features. The origin of the interior of a cultural building is the certainty of determining the function of the statue. The discovery in the lower part of the cell of the stag temple of the famous sfirela from the Apolline triad is in fact the main reason for their identification with images of temple worship, as well as fragments of a colossal worship statue of the temple of an Athenian priest and several other fragments of marble goddess statues found in similar contexts.

A contemporary of these artists was Smilid, who owned a wooden image of Hera in her Samos temple.

The most significant of the ancient Greek marble sculptors, according to legend, were natives of the Ionian island of Chios: Melas, Mikkiades, Arhermus, Bupal and Athenis.

But the first famous marble sculptors are considered to be Dipoin and Skilid. Founders of chryselephantine technology.

Lack of archaeological direct evidence Archaic and Classical ages correspond to the richer documentation of Hellenistic and Roman times. Rare evidence is almost completely preserved. Most often this was the restoration of simple fragments or, in the case of statues made using the acrolein technique, parts of the Marble body, legs, arms, arms or heads. In rare cases, thanks to the "abundance of fragments" it was possible to restore a statue, as for the statue of the group of the temple of Despoina in Lycosura, made by Damophon of Messene.

And our shadows rush behind us

Usually the absence of a find prevents, without the support of other sources, the reconstruction of the general appearance of the statue or the determination of its typological and formal characteristics. In other cases, evidence of money marks an alliance between known statues of the copying tradition and literary evidence of statues of worship. For strictly religious reasons and iconological convention, even before its formal values, c. it is sometimes imposed as an example of a small votive plastic dedicated to the sanctuary.

The name of the Attic artist is preserved in one of the inscriptions that has reached us - Aristocles. He put his signature on the beautiful tombstone of Aristion.

The pediment groups of the Aegina Temple of Athena are believed to be the works of Onatus. The gables depicted the battle of Troy.

Let us now turn to round plastic figures. The gradual progress in the development of forms is most noticeable in the female statues, namely in the freer arrangement of folds in clothes and in the more natural appearance of hair.

The male statues of the last times of archaism already show signs of the same progress. One can highlight the figures of Apollo from Piombino, Apollo, found in Pompeii.

So, we see that Greek art by the time of the Persian wars had reached almost the same stage of development everywhere. The time of external influences had already passed by art and the artists of various parts of Greece strived for a mutual exchange of personal gains among themselves and for friendly equality.

CHAPTER 2. OUTSTANDING SCULPTORS OF THE ARCHAIC ERA

The archaic period is a period of formation ancient greek sculpture. The sculptor’s desire to convey the beauty of the ideal is already clear. human body, which was fully manifested in the works of more late era, but it was still too difficult for the artist to move away from the shape of the stone block, and the figures of this period are always static.

The first monuments of ancient Greek sculpture of the archaic era are determined by the geometric style (8th century). These are sketchy figurines found in Athens, Olympia, and Boeotia. The archaic era of ancient Greek sculpture falls on the 7th - 6th centuries. (early archaic - about 650 - 580 BC; high - 580 - 530; late - 530 - 500/480). The beginning of monumental sculpture in Greece dates back to the middle of the 7th century. BC e. and is characterized by orientalizing styles, of which the most important was the Daedalian style, associated with the name of the semi-mythical sculptor Daedalus. The circle of “Daedalus” sculpture includes the statue of Artemis of Delos, the creation of the hands of Daedalus’ student Endius. And a female statue of Cretan work, kept in the Louvre (“Lady of Auxerre”). Mid-7th century BC e. The first kouroses also date back. The first sculptural temple decoration dates back to the same time - reliefs and statues from Prinia on the island of Crete. Subsequently, the sculptural decoration fills the fields highlighted in the temple by its very design - pediments and metopes in the Doric temple, a continuous frieze (zophorus) in the Ionic one. The earliest pediment compositions in ancient Greek sculpture come from Athens Acropolis and from the Temple of Artemis on the island of Kerkyra (Corfu). Funerary, dedicatory and cult statues are represented in the archaic by the type of kouros and kora. Archaic reliefs decorate the bases of statues, pediments and metopes of temples (later, round sculptures take the place of reliefs in the pediments), and tombstones. Among the famous monuments of archaic round sculpture are the head of Hera, found near her temple in Olympia, the statues of Cleobis and Biton from Delphi, Moschophorus (“Taurus Bearer”) from the Athenian Acropolis, Hera of Samos, statues from Didyma, Nikka Arherma, etc. The last statue demonstrates the archaic a diagram of the so-called “kneeling run”, used to depict a flying or running figure. In archaic sculpture, a whole series of conventions are also adopted - for example, the so-called “archaic smile” on the faces of archaic sculptures.

The sculpture of the Archaic era is dominated by statues of slender naked youths and draped young girls - kouros and koras. Neither childhood nor old age attracted the attention of artists then, because only in mature youth are vital forces in full bloom and balance. Early Greek sculptors created images of Men and Women in their ideal version.

In that era, spiritual horizons expanded unusually; man seemed to feel himself standing face to face with the universe and wanted to comprehend its harmony, the secret of its integrity. Details eluded, ideas about the specific “mechanism” of the universe were the most fantastic, but the pathos of the whole, the consciousness of universal interconnection - this was what constituted the strength of the philosophy and art of archaic Greece.

Just as philosophy, then still close to poetry, shrewdly guessed the general principles of development, and poetry - the essence of human passions, fine art created a generalized human appearance. Let's look at the kouros, or, as they are sometimes called, "archaic Apollos." It is not so important whether the artist really intended to depict Apollo, or a hero, or an athlete. qh depicted a Man. The man is young, naked, and his chaste nakedness does not need shameful coverings. He always stands straight, his body is imbued with a readiness to move. The body structure is shown and emphasized with utmost clarity; You can immediately see that the long muscular legs can bend at the knees and run, the abdominal muscles can tense, the chest can swell with deep breathing. The face does not express any specific experience or individual character traits, but the possibilities of various experiences are hidden in it. And the conventional “smile” - slightly raised corners of the mouth - is only the possibility of a smile, a hint of the joy of being inherent in this seemingly newly created person.

Kouros statues were created mainly in areas where the Dorian style dominated, that is, on the territory of mainland Greece; female statues - kora - mainly in Asia Minor and island cities, centers of the Ionian style. Beautiful female figures were found during excavations of the archaic Athenian Acropolis, built in the 6th century BC. e., when Pisistratus ruled there, and destroyed during the war with the Persians. For twenty-five centuries marble crusts were buried in “Persian garbage”; Finally they were taken out of there, half broken, but without losing their extraordinary charm. Perhaps some of them were performed by Ionian masters invited by Pisistratus to Athens; their art influenced Attic plasticity, which now combines the features of Dorian severity with Ionian grace. In the barks of the Athenian Acropolis, the ideal of femininity is expressed in its pristine purity. The smile is bright, the gaze is trusting and as if joyfully amazed at the spectacle of the world, the figure is chastely draped with a peplos - a veil, or a light robe - a chiton (in the archaic era, female figures, unlike male ones, were not yet depicted naked), hair flows over the shoulders in curly strands. These kora stood on pedestals in front of the temple of Athena, holding an apple or flower in their hand.

Archaic sculptures (as well as classical ones) were not as monotonously white as we imagine them now. Many still have traces of painting. The marble girls' hair was golden, their cheeks were pink, and their eyes were blue. Against the background of the cloudless sky of Hellas, all this should have looked very festive, but at the same time strict, thanks to the clarity, composure and constructiveness of the forms and silhouettes. There was no excessive floweriness or variegation.

The search for rational foundations of beauty, harmony based on measure and number is very important point in Greek aesthetics. Pythagorean philosophers sought to grasp the natural numerical relationships in musical harmonies and in the arrangement of heavenly bodies, believing that musical harmony corresponds to the nature of things, the cosmic order, the “harmony of the spheres.” Artists were looking for mathematically verified proportions of the human body and the “body” of architecture. In this, early Greek art was fundamentally different from Cretan-Mycenaean art, which was alien to any mathematics.

Thus, in the archaic era, the foundations of ancient Greek sculpture, directions and options for its development were laid. Even then, the main goals of sculpture, aesthetic ideals and aspirations of the ancient Greeks were clear. In later periods, these ideals and the skill of ancient sculptors developed and improved.

CHAPTER 3. OUTSTANDING SCULPTORS OF THE CLASSICAL ERA

The classical period of ancient Greek sculpture falls on the V - IV centuries BC. (early classic or “strict style” - 500/490 - 460/450 BC; high - 450 - 430/420 BC; “rich style” - 420 - 400/390 BC; Late Classic - 400/390 - ca. 320 BC). At the turn of two eras - archaic and classical - stands the sculptural decor of the Temple of Athena Aphaia on the island of Aegina. The sculptures of the western pediment date back to the time of the founding of the temple (510 - 500 BC), the sculptures of the second eastern pediment, which replaced the previous ones, date back to the early classical period (490 - 480 BC). The central monument of ancient Greek sculpture of the early classics is the pediments and metopes of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (about 468 - 456 BC). Another significant work of early classics is the so-called “Throne of Ludovisi”, decorated with reliefs. A number of bronze originals have also survived from this time - the “Delphic Charioteer”, the statue of Poseidon from Cape Artemisium, Bronzes from Riace. The largest sculptors of the early classics are Pythagoras of Rhegium, Calamis and Myron. We judge the work of famous Greek sculptors mainly from literary evidence and later copies of their works. High classics are represented by the names of Phidias and Polykleitos. Its short-term heyday is associated with work on the Athenian Acropolis, that is, with the sculptural decoration of the Parthenon (pediments, metopes and zophoros survived, 447 - 432 BC). The pinnacle of ancient Greek sculpture was, apparently, the chrysoelephantine statues of Athena Parthenos and Olympian Zeus by Phidias (both have not survived). The largest sculptors of the late classics are Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos, who in many ways anticipated the subsequent era of Hellenism.

3.1. Myron of Eleuther

MIRON, Greek sculptor 5th century BC, representative of the transitional period in sculpture from the early classics to the art of Periclean times. Born in Boeotia. His activity dates back to approximately the middle of the 5th century. - the time of victories of three athletes, whose statues he sculpted in 456, 448 and 444 BC. Myron was an older contemporary of Phidias and Polykleitos and was considered one of the greatest sculptors of his time. He worked in bronze, but none of his works have survived; they are known mainly from copies. Myron's most famous work is the Discus Thrower. The discus thrower is depicted in a difficult pose at the moment of highest tension before the throw. The sculptor was interested in the shape and proportionality of figures in motion. Myron was a master of conveying movement into a climactic, transitional moment. In the laudatory epigram dedicated to his bronze statue of the athlete Ladas, it is emphasized that the heavily breathing runner is conveyed with unusual vividness. The sculptural group of Myron Athena and Marsyas, standing on the Athenian Acropolis, is marked by the same skill in conveying movement.

3.2. The greatest Phidias and Polykleitos

PHIDIAS, an ancient Greek sculptor considered by many to be the greatest artist of antiquity. Phidias was a native of Athens, his father's name was Charmides. Phidias studied the skill of a sculptor in Athens at the school of Hegeias and in Argos at the school of Agelas (in the latter, perhaps at the same time as Polykleitos). Among the existing statues there is not a single one that undoubtedly belonged to Phidias. Our knowledge of his work is based on descriptions of ancient authors, on the study of later copies, as well as surviving works that are attributed to Phidias with more or less certainty.

Among Phidias's early works, created c. 470–450 BC, should be called cult statue Athens Areia in Plataea, made of gilded wood (clothing) and Pentelic marble (face, arms and legs). By the same period, approx. 460 BC, dates back to memorial Complex in Delphi, built in honor of the victory of the Athenians over the Persians in the Battle of Marathon. At the same time (c. 456 BC), and also using funds from the booty captured in the Battle of Marathon, Phidias erected a colossal bronze statue of Athena Promachos (Processress) on the Acropolis. Another bronze statue of Athena on the Acropolis, the so-called. Athena Lemnia, who holds a helmet in her hand, was created by Phidias c. 450 BC by order of Attic colonists sailing to the island of Lemnos. Perhaps the two statues located in Dresden, as well as the head of Athena from Bologna, are copies of it.

The chrysoelephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Zeus at Olympia was considered in ancient times to be the masterpiece of Phidias. Dion Chrysostomos and Quintilian (1st century AD) say that thanks to the unsurpassed beauty and godly creation of Phidias, religion itself was enriched, and Dion adds that anyone who happened to see this statue forgets all his sorrows and adversities. Detailed description Pausanias has a statue considered one of the seven wonders of the world. Zeus was depicted sitting. In the palm of his right hand stood the goddess Nike, and in his left he held a scepter, on top of which sat an eagle. Zeus was bearded and long-haired, with a laurel wreath on his head. The seated figure almost touched the ceiling with his head, so that it seemed that if Zeus stood up, he would blow the roof off the temple. The throne was richly decorated with gold, ivory and precious stones. In the upper part of the throne above the head of the statue, the figures of the three Charites were placed on one side, and the three seasons of the year (Or) on the other; dancing Niki were depicted on the legs of the throne. On the crossbars between the legs of the throne stood statues representing the Olympic competitions and the battle of the Greeks (led by Hercules and Theseus) with the Amazons. The pedestal of the throne, made of black stone, was decorated with golden reliefs depicting the gods, in particular Eros, who meets Aphrodite emerging from the sea waves, and Peyto (goddess of persuasion) crowning her with a wreath. A statue of Olympian Zeus or one of his heads was depicted on coins that were minted in Elis. There was no clarity regarding the time of creation of the statue in antiquity, but since the construction of the temple was completed ca. 456 BC, most likely the statue was erected no later than c. 450 BC (there have now been renewed attempts to place Zeus from Olympia to a time after the Athena Parthenos).

When Pericles launched extensive construction in Athens, Phidias headed all the work on the Acropolis, among other things, the construction of the Parthenon, which was carried out by the architects Ictinus and Callicrates in 447–438 BC. The Parthenon, the temple of the patron goddess of the city of Athens, one of the most famous creations of ancient architecture, was a Doric peripterus. Extensive plastic decoration of the temple was performed by large group sculptors, working under the supervision of Phidias and, probably, according to his sketches (the most famous are the relief friezes of the Parthenon and the fragmentarily preserved statues from the pediments, now in the British Museum).

The cult chrysoelephantine statue of Athena Parthenos that stood in the temple, which was completed in 438 BC, was sculpted by Phidias himself. The description of Pausanias and numerous copies give a fairly clear idea of it. Athena was depicted standing at full height, wearing a long chiton hanging in heavy folds. On the palm of Athena's right hand stood the winged goddess Nike; on Athena's chest was an aegis with the head of Medusa; in her left hand the goddess held a spear, and a shield was leaning against her feet. The sacred snake of Athena (Pausanias calls it Erichthonius) curled up around the spear. The statue's pedestal depicted the birth of Pandora (the first woman). As Pliny the Elder writes, on the outside of the shield there was a battle with the Amazons, on the inside there was a fight between gods and giants, and on Athena’s sandals there was an image of a centauromachy. On the head of the goddess there was a helmet crowned with three crests, the middle of which represented a sphinx, and the side ones were griffins. Athena had jewelry: necklaces, earrings, bracelets.

The similarity of the style with the sculptures and reliefs of the Parthenon is felt in the statues of Demeter (copies of it are in Berlin and Cherchel, Algeria) and Kore (copy in the Villa Albani). Motifs from both statues are used in the famous large votive relief from Eleusis (Athens, Archaeological Museum), a Roman copy of which is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The folds of Cora's robe are similar in style to the drapery of the standing Zeus statue, a copy of which is kept in Dresden, and the torso, possibly a fragment of the original, is in Olympia. Similar in style to the Parthenon frieze is Anadumen (a young man tying a bandage around his head); it may have been created as a response to the Diadumen of Polykleitos. The statue of Phidias is much more natural in terms of posture and gesture, but somewhat rougher. Together with Polykleitos and Cresilaus, Phidias took part in the competition for a statue of a wounded Amazon for the temple of Artemis in Ephesus and took second place after Polykleitos; a copy of his statue is considered to be the so-called. Amazon Mattei (Vatican). Wounded in the thigh, the Amazon tucked her chiton into her belt; to reduce the pain, she leans on the spear, grasping it with both hands, with the right one raised above her head. As with the Athena Parthenos and the Parthenon reliefs, rich content is contained here in a simple form.

The creations of Phidias are grandiose, majestic and harmonious; form and content are in perfect balance in them. The master's students, Alkamen and Agorakrit, continued to work in his style in the last quarter of the 5th century. BC, and many other sculptors, among them Kephisodotus, - and in the first quarter of the 4th century. BC.

POLYCLETUS (5th century BC), ancient Greek sculptor and art theorist, worked ca. 460–420 BC Born in Sikyon c. 480 BC, studied in Argos with Ageladus, possibly at the same time as Phidias, and later headed the Argive school of sculptors. It was believed that no one could compare with Polykleitos in the depiction of athletes, while Phidias was recognized as the first in the depiction of the gods. Around 460–450 BC Polykleitos created several statues of the victors Olympic Games, incl. Kiniska (its pedestal was found during excavations at Olympia). Perhaps its copy is a statue of an athlete putting on a wreath (the so-called Westmacott Youth from the British Museum). Other works from the early period of Polykleitos's work are the Discophore (The Disc Bearer, the best copies in Wellesley College near Boston, USA, and in the Vatican) and Hermes (an idea of it can be gleaned from a bronze figurine from the British Museum). However, Polykleitos's most famous work is created c. 450–440 BC Doryphoros (Spearman). The best copies of this statue are in Naples, the Vatican and Florence; the best surviving copy of the head of Doryphorus was made in bronze by the sculptor Apollonius, son of Archias (found in Herculaneum, it is now in Naples). It is in this work that Polykleitos’ ideas about ideal proportions human body, which are in numerical relationship with each other. It was believed that the figure was created on the basis of the principles of Pythagoreanism, therefore in ancient times the statue of Doryphorus was often called the “canon of Polykleitos,” especially since the Canon was the name of his unpreserved treatise on aesthetics. Here the rhythmic composition is based on the principle of asymmetry (the right side, i.e. the supporting leg and the arm hanging along the body, are static, but charged with force, the left, i.e. the leg remaining behind and the arm with the spear, disturb the peace, but are somewhat relaxed ), which revives her and makes her mobile. The forms of this statue are extremely clear; they are repeated in most of the works of the sculptor and his school.

Commissioned by the priests of the Temple of Artemis of Ephesus c. 440 BC Polykleitos created a statue of a wounded Amazon, taking first place in a competition where, in addition to him, Phidias and Cresilaus participated. An idea of it is given by copies - a relief discovered in Ephesus, as well as statues in Berlin, Copenhagen and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The Amazon's legs are set in the same way as Doryphoros's, but the free arm does not hang along the body, but is thrown behind the head; the other hand supports the body, leaning on the column. The pose is harmonious and balanced, but Polykleitos did not take into account the fact that if there is a wound under a person’s right chest, his right arm cannot be raised high up. Apparently, the beautiful, harmonious form interested him more than the plot or the transfer of feelings. The same care is imbued with the careful development of the folds of the short Amazon chiton.

Polykleitos then worked in Athens, where approx. 420 BC he created Diadumen, a young man with a bandage around his head. In this work, which was called a gentle youth, in contrast to the courageous Doryphoros, one can feel the influence of the Attic school. Here again the motif of a step is used, although both arms are raised and holding the bandage, a movement that would be better suited to a calm and steady position of the legs. The opposition between the right and left sides is not so pronounced. The facial features and voluminous curls of hair are much softer than in previous works. The best repetitions of Diadumen are a copy found at Delos and now in Athens, a statue from Vaison in France, which is kept in the British Museum, and copies in Madrid and in the Metropolitan Museum. Several terracotta and bronze figurines have also survived. The best copies of Diadumen's head are in Dresden and Kassel.

Around 420 BC Polykleitos created a colossal chrysoelephantine (gold and ivory) statue of Hera seated on a throne for the temple at Argos. Argive coins may give some idea of what this ancient statue looked like. Next to Hera stood Hebe, sculptured by Naucis, a student of Polykleitos. In the plastic design of the temple one can feel both the influence of the masters of the Attic school and Polycletus; perhaps this is the work of his students. Polykleitos's creations lacked the majesty of Phidias's statues, but many critics consider them superior to Phidias in their academic perfection and ideal poise of posture. Polykleitos had numerous students and followers until the time of Lysippos (late 4th century BC), who said that Doryphoros was his teacher in art, although he later departed from Polykleitos’s canon and replaced it with his own.

3.3. Representatives of the late classics (Praxiteles, Scopas and Lysippos)

PRAXITELES (4th century BC), ancient Greek sculptor, born in Athens c. 390 BC Perhaps Praxiteles is the son and student of Kephisodotus the Elder. Praxiteles worked in hometown in 370–330 BC, and in 350–330 BC. also sculpted in Mantinea and Asia Minor. His works, mostly in marble, are known mainly from Roman copies and testimonies of ancient authors.

The best idea of the style of Praxiteles is given by the statue of Hermes with the infant Dionysus (Museum at Olympia), which was found during excavations in the Temple of Hera at Olympia. Despite doubts that have been expressed, this is almost certainly an original, created c. 340 BC The flexible figure of Hermes gracefully leaned against the tree trunk. The master managed to improve the interpretation of the motif of a man with a child in his arms: the movements of both hands of Hermes are compositionally connected with the baby. Probably, in his right, unpreserved hand there was a bunch of grapes, with which he teased Dionysus, which is why the baby reached for it. The poses of the heroes moved even further away from the constrained straightness observed in earlier masters. The figure of Hermes is proportionally built and perfectly worked out, the smiling face is full of liveliness, the profile is graceful, and the smooth surface of the skin contrasts sharply with the schematically outlined hair and the woolly surface of the cloak thrown over the trunk. The hair, drapery, eyes and lips, and sandal straps were painted. The painting of statues by Praxiteles was not only for decorative effect: he considered it an extremely important matter and entrusted it to famous artists, for example Nicias from Athens and others.

The masterful and innovative execution of Hermes has made it the most famous work of Praxiteles in modern times; however, in ancient times, his masterpieces were considered to be the statues of Aphrodite, Eros and satyrs that have not reached us. Judging by the surviving copies, they existed in several versions.

The statue of Aphrodite of Knidos was considered in ancient times not only the best creation of Praxiteles, but generally the best statue of all time. As Pliny the Elder writes, many came to Cnidus just to see her. It was the first monumental depiction of a completely naked female figure in Greek art, and therefore it was rejected by the inhabitants of Kos, for whom it was intended, after which it was bought by the townspeople of neighboring Knidos. In Roman times, the image of this statue of Aphrodite was minted on Cnidian coins, and numerous copies were made from it (the best of them is now in the Vatican, and the best copy of the head of Aphrodite is in the Kaufmann collection in Berlin). In ancient times it was claimed that Praxiteles' model was his lover, the hetaera Phryne.

Other statues of Aphrodite attributed to Praxiteles are less well represented. There is no copy of the statue chosen by the people of Kos. The Aphrodite of Arles, named after the place where it was found and kept in the Louvre, may not depict Aphrodite, but Phryne. The legs of the statue are hidden by drapery, and the torso is completely naked; judging by her pose, there was a mirror in her left hand. Several elegant figurines of a woman putting on a necklace have also survived, but in them again one can see both Aphrodite and a mortal woman.

Statues of Eros by Praxiteles were located in Thespiae in Boeotia and in Paria in Troas. An idea of them can be given by the graceful and elegant figures of Eros on coins, medallions and gems, where he is represented leaning on a column and supporting his head with his hand, or next to the herm, as on coins from Paria. The torsos of similar statues from Bay (kept in Naples and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) and from the Palatine Hill (in the Louvre and in the museum in Parma) have been preserved.

From copies, two versions of the statue of a young satyr are known, one of which may belong to the early period of Praxiteles’ work, and the other to the mature period. The first type of statue depicts a satyr pouring wine with his right hand from a highly held jug into a cup in his other hand; he has a bandage and a wreath of ivy on his head, his facial features are noble, his profile is thin. The best copies of this type are found in Castel Gandolfo, in Anzio and in Torre del Greco. In the second version (it was copied more often, the best statues are in the Torlonia Museum and in the Capitoline Museum in Rome; to these should be added the torso from the Palatine Hill, kept in the Louvre) depicted a satyr leaning on a tree trunk, holding a flute in his right hand, and with his left, throwing back the panther skin thrown over his shoulder.

The motif of a figure leaning on a support is also used in the statue of Dionysus, the best copy of which is in Madrid. Dionysus rests on a herm reminiscent of the herm of the sculptor Alcamenes, the same as in Hermes by Cephisodotus. The statue of Apollo Lyceum, so called because it was located in the Athenian gymnasium Lyceum, is reproduced on Attic coins. Apollo here leans on a column and supports his head with his right hand, and in his left hand there is a bow. Quite a few copies of this statue have survived, the best of which are in the Louvre and in the Capitoline Museum in Rome. There are also copies of the statue of the young Apollo Sauroctone (Apollo killing a lizard) - in the Louvre, in the Vatican, at the Villa Albani in Rome, etc.

In two versions of the statue of Artemis created by Praxiteles, we see examples of the solution to the motif of a draped human figure. One of them depicts a young huntress dressed in a simple peplos, who takes an arrow from a quiver behind her back. The best copy of this type is Artemis, kept in Dresden. The second option is the so-called. Artemis Bravronia from the Athenian Acropolis, dating back to 345 BC, belongs to late period creativity of the master. It is believed that a copy of it is a statue found in Gabii and kept in the Louvre. Artemis is depicted here as the patroness of women: she throws on right shoulder a cover brought by a woman as a gift for successful delivery of a burden.

One of the last works of Praxiteles is the group of Leto with Apollo and Artemis, fragments of which were found in Mantinea. On the pedestal, the sculptor sculpted a relief depicting the competition between Apollo and Marsyas in the presence of nine muses; the relief (entirely, except for the figures of the three muses) was found and is now located in Athens. The folds of the draperies reveal a wealth of graceful plastic motifs.

Praxiteles was an unsurpassed master in conveying the grace of the body and the subtle harmony of the spirit. Most often, he depicted gods, and even satyrs, as young; in his work replaced the majesty and sublimity of the images of the 5th century. BC. grace and dreamy tenderness come. The art of Praxiteles was continued in the works of his sons and students, Cephisodotus the Younger and Timarchus, who worked on orders from the Ptolemies on the island of Kos and transferred the sculptor’s style to the East. In the Alexandrian imitations of Praxiteles, his characteristic tenderness turns into weakness and sluggish lifelessness.

SKOPAS (flourished 375–335 BC), Greek sculptor and architect, born on the island of Paros c. 420 BC, possibly son and student of Aristander. The first work of Skopas known to us is the temple of Athena Alea in Tegea, in the Peloponnese, which had to be rebuilt since the previous one burned down in 395 BC. The project has an interesting solution: unusually slender Doric columns along the perimeter and Corinthian semi-columns inside the cella. The eastern pediment depicted the hunt for the Calydonian boar, and the western pediment depicted the duel between the local hero Telephus and Achilles; Scenes from the myth of Telephes were reproduced on the metopes. The heads of Hercules, warriors, hunters and a boar, as well as fragments of male statues and a female torso, probably Atalanta, have been preserved.

Skopas was one of a group of four sculptors (and may have been the eldest among them) who were commissioned by Mausolus' widow Artemisia to create the sculptural part of the Mausoleum (one of the Seven Wonders of the World) at Halicarnassus, the tomb of her husband. It was completed approx. 351 BC Skopas owns the sculptures on the eastern side; the slabs of the eastern frieze are characterized by the same style as the statues from Tegea. The passion inherent in Skopas’s works is achieved primarily through a new interpretation of the eyes: they are deep-set and surrounded by heavy folds of the eyelids. The liveliness of movements and bold positions of the bodies express intense energy and demonstrate the ingenuity of the master.

Scopas's most famous work was the group of sea deities in the sanctuary of Neptune in Rome, who perhaps accompanied Achilles on his journey to the Isles of the Blessed. Possibly a frieze with Poseidon, Amphitrite, Tritons and Nereids riding on sea monsters(now in Munich), and the scene of sacrifice (now in the Louvre) represented the foundation on which this group was located in Rome in the 1st century. AD A statue of Apollo with a lyre by Scopas stood in a temple on the Roman Palatine between Artemis by Timothy and Leto the younger Kephisodotus. All three are copied on a pedestal from Sorrento, and Apollo is also copied in a statue (in Munich) and in a torso (in Palazzo Corsini in Rome). Other works attributed to Scopas are Aphrodite Pandemos riding on a goat (in Elis, there are images on coins), Aphrodite and Potos (from the island of Samothrace), Potos with Eros and Himera (from Megara), as well as three statues in Rome - a colossal seated the figure of Ares, the seated Hestia and the naked Aphrodite, which some connoisseurs placed above the famous Aphrodite of Cnidus, owned by Praxiteles.

LYSIPPUS (c. 390 - c. 300 BC), ancient Greek sculptor, born in Sikyon (Peloponnese). In antiquity it was claimed (Pliny the Elder) that Lysippos created 1,500 statues. Even if this is an exaggeration, it is clear that Lysippos was an extremely prolific and versatile artist. The bulk of his works were predominantly bronze statues depicting gods, Hercules, athletes and other contemporaries, as well as horses and dogs. Lysippos was the court sculptor of Alexander the Great. A colossal statue of Zeus by Lysippos stood in the agora of Tarentum. According to the same Pliny, its height was 40 cubits, i.e. 17.6 m. Other statues of Zeus were erected by Lysippos in the agora of Sicyon, in the temple at Argos and in the temple of Megara, the latter work representing Zeus accompanied by the Muses. An image of a bronze statue of Poseidon with one leg on a raised platform that stood in Sikyon is found on surviving coins; a copy of it is a statue resembling the image on coins in the Lateran Museum (Vatican). The figure of the sun god Helios, created by Lysippos in Rhodes, depicted the god on a chariot drawn by four; this motif was used by the sculptor in other compositions. Copies in the Louvre, the Capitoline Museums and the British Museum depicting Eros loosening the string of a bow probably go back to the Eros of Lysippos at Thespiae. Also located in Sikyon, the statue depicted Kairos (god of luck): the god in winged sandals sat on a wheel, his hair hung forward, but the back of his head was bald; copies of the statue survive on small reliefs and cameos.

Hercules is Lysippos’s favorite character. The colossal seated figure of Hercules on the acropolis of Tarentum depicted the hero in a gloomy mood after he had cleared the Augean stables: Hercules sat on a basket in which he carried dung, his head resting on his arm, his elbow resting on his knee. This statue was taken by Fabius Maximus to Rome after it was destroyed in 209 BC. took Tarentum, and in 325 AD. Constantine the Great transported her to the newly founded Constantinople. Perhaps the Hercules we see on coins from Sikyon goes back to a lost original, copies of which are both the Farnese Hercules in Naples and the statue signed with the name of Lysippos in Florence. Here we again see the gloomy Hercules, dejectedly leaning on a club, with a lion's skin draped over it. The statue of Hercules Epitrapedius, depicting the hero “at the table,” represented him, according to the descriptions and the many existing repetitions of different sizes, sitting on stones, with a cup of wine in one hand and a club in the other - probably after he had ascended to Olympus. The figurine, which was originally a table decoration created for Alexander the Great, was subsequently seen in Rome by Statius and Martial.

The portraits of Alexander created by Lysippos were praised for the combination of two qualities. Firstly, they realistically reproduced the model’s appearance, including the unusual turn of the neck, and secondly, the courageous and majestic character of the emperor was clearly expressed here. The figure representing Alexander with a spear appears to have served as the original for both the herm formerly owned by José Nicolas Azar and the bronze figurine (both now in the Louvre). Lysippos depicted Alexander on horseback, both alone and with his comrades who died in the Battle of Granicus in 334 BC. An existing equestrian bronze statue of Alexander with a stern oar under his horse, perhaps an allusion to the same battle on the river, may be a replica of the latter statue. Other portraits by Lysippos included that of Socrates (the best copies are perhaps the busts in the Louvre and the Museo Nazionale delle Terme in Naples); portrait of Aesop; there were still portraits of the poetess Praxilla and Seleucus. Together with Leochares, Lysippos created for Craterus a group depicting the scene of a lion hunt, in which Craterus saved Alexander's life; after 321 BC the group was initiated into Delphi.

Apoxyomenes, an athlete scraping off dirt from himself after exercise (in antiquity they used to anoint themselves before athletic activities), was subsequently placed by Agrippa in front of the baths he built in Rome. Perhaps its copy is a marble statue in the Vatican. With a scraper held in the left hand, the athlete cleans the right hand extended forward. Thus, the left arm crosses the body, which was the first instance of movement in the third dimension that we encounter in ancient Greek sculpture. The head of the statue is smaller than was customary in the earlier sculpture, the facial features are nervous and delicate; Hair disheveled from exercise is reproduced with great vividness.

Another portrait image of an athlete by Lysippos is the marble Agios found in Delphi (located in the Delphi Museum); the same signature as under it was also found in Pharsal, but no statue was found there. Both inscriptions list the many victories of Agius, the ancestor of the Thessalian ruler Daoch, who commissioned the statue, and the inscription from Pharsalus lists Lysippos as the author of the work. The statue found at Delphi resembles Scopas in style, who in turn was influenced by Polykleitos. Since Lysippos himself called Doryphorus Polycletus his teacher (whose angular proportions he, however, rejected), it is quite possible that he was also influenced by his older contemporary Scopas.

Lysippos is at the same time the last of the great classical masters and the first Hellenistic sculptor. Many of his students, among whom were his own three sons, had a profound impact on the art of the 2nd century. BC.

CHAPTER 4. SCULPTORS OF THE HELLENISM ERA

The states of the Diadochi existed in Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor; the most powerful and influential was the Egyptian state of the Ptolemies. Despite the fact that the countries of the East had their own, very ancient and very different from Greek artistic traditions, the expansion of Greek culture overpowered them. The very concept of “Hellenism” contains an indirect indication of the victory of the Hellenic principle, of the Hellenization of these countries. Even in remote areas Hellenistic world, in Bactria and Parthia (present-day Central Asia), uniquely transformed ancient forms of art appear.

Pomp and intimacy are opposite traits; Hellenistic art is full of contrasts - gigantic and miniature, ceremonial and everyday, allegorical and natural. The world has become more complex, and aesthetic needs have become more diverse. The main trend is a departure from the generalized human type to an understanding of man as a concrete, individual being, and hence the increasing attention to his psychology, interest in events, and a new vigilance to national, age, social and other signs of personality. But since all this was expressed in a language inherited from the classics, which did not set themselves such tasks, a certain inorganicity is felt in the innovative sculptural works of the Hellenistic era; they do not achieve the integrity and harmony of their great predecessors. The portrait head of the heroic statue “Diadochi” does not fit with his naked torso, which repeats the type of a classical athlete. The drama of the multi-figure sculptural group “Farnese Bull” is contradicted by the “classical” representativeness of the figures; their poses and movements are too beautiful and smooth to believe in the truth of their experiences. In numerous park and chamber sculptures, the traditions of Praxiteles are diminished: Eros, “the great and powerful god,” turns into a playful, playful Cupid; Apollo - into the flirtatious and effeminate Apollo; strengthening the genre does not benefit them. And the famous Hellenistic statues of old women carrying provisions, a drunken old woman, an old fisherman with a flabby body lack the power of figurative generalization; art masters these new types externally, without penetrating into the depths - after all, the classical heritage did not provide the key to them.

All of the above does not mean that the Hellenistic era did not leave behind great sculptors and their monuments of art. Moreover, she created works that, in our opinion, synthesize the highest achievements of ancient sculpture and are its unattainable examples - Aphrodite of Melos, Nike of Samothrace, the altar of Zeus in Pergamon. These famous sculptures were created during the Hellenistic era. Their authors, about whom nothing or almost nothing is known, worked in line with the classical tradition, developing it truly creatively.

Among the sculptors of this era, the following names can be noted: Apollonius, Tauriscus (“Farnese Bull”), Athenodorus, Polydorus, Agesander (“Aphrodite of Melos,” “Laocoon”).

The Novo-Attic masters were essentially only copyers. So, for example, Antiochus of Athens reproduced Athena parthinos Phidias in his statue of Athena. The Novo-Attic school was very willing to decorate large marble vases with reliefs. Among the masters of this industry are: Salpion, Sosibius, Pontius.

Morals and forms of life, as well as forms of religion, began to mix in the Hellenistic era, but friendship did not reign and peace did not come, strife and war did not stop. The wars of Pergamum with the Gauls are only one of the episodes. When the victory over the Gauls was finally won, the altar of Zeus was erected in her honor, completed in 180 BC. e.

Battles and fights were a frequent theme in ancient reliefs, starting from the archaic, they were never depicted as on the Pergamon Altar - with such a shuddering feeling of a cataclysm, a battle for life and death, where all the cosmic forces, all the demons of the earth participate and the sky. The structure of the composition has changed, it has lost its classical clarity and has become swirling and confusing. The sculpture depicts the desperate and clearly futile efforts of the hero to free himself from the clutches of the monsters, which wrapped tightly around the bodies of the three victims, squeezing and biting them. The futility of struggle and the inevitability of death are obvious.

CONCLUSION

We looked at the creations of the greatest sculptors of Ancient Greece throughout the entire period of antiquity. We saw the entire process of formation, flourishing and decline of sculpture styles - the entire transition from strict, static and idealized archaic forms through balanced harmony classical sculpture to the dramatic psychologism of Hellenistic statues. The creations of the sculptors of Ancient Greece were rightfully considered a model, an ideal, a canon for many centuries, and now it never ceases to be recognized as a masterpiece of world classics. Nothing like this has been achieved before or since. All modern sculpture can be considered to one degree or another a continuation of the traditions of Ancient Greece. The sculpture of Ancient Greece went through a difficult path in its development, preparing the ground for the development of sculpture in subsequent eras in various countries.

It is known that most ancient masters of plastic art did not sculpt in stone, they cast in bronze. In the centuries following the era of Greek civilization, the preservation of bronze masterpieces was preferred to melting them down into domes or coins, and later into cannons.

In later times, the traditions laid down by ancient Greek sculptures were enriched with new developments and achievements, while the ancient canons served as the necessary foundation, the basis for the development of plastic art of all subsequent eras.

LIST OF SOURCES USED

1. Ancient culture. Dictionary-reference book/under general. ed. V.N. Yarkho - M., 2002

2. Bystrova A. N. “The world of culture, the foundations of cultural studies”

Polikarpov V.S. Lectures on cultural studies - M.: “Gardarika”, “Expert Bureau”, 1997

3. Whipper B.R. Art of Ancient Greece. – M., 1972

4. Gnedich P.P. World History of Arts - M., 2000

5. Gribunina N.G. History of world artistic culture, in 4 parts. Parts 1, 2. – Tver, 1993

6. Dmitrieva, Akimova. Ancient art. Essays. – M., 1988

7. Kolobova K.M. Ancient city Athens and its monuments - L., 1961

8. Kolpinsky Yu.D. Sculpture ancient Hellas. – M., 1963

9. Miretskaya N.V., Miretskaya E.V. Lessons from ancient culture. - Obninsk, 1998

10. Polevoy L.M. Art of Greece. Ancient world. – M., 1970

11. Rivkin B.I. Ancient art. – M., 1972

Ancient culture. Dictionary-reference book/under general. ed. V.N. Yarkho - M., 2002, p. 153

Dmitrieva, Akimova. Ancient art. Essays. – M., 1988. P. 35

Rivkin B.I. Ancient art. – M., 1972, p. 172

Stages of development of ancient Greek sculpture:

Archaic

Classic

Hellenism

BARK(from Greek kore - girl),

BARK(from Greek kore - girl),

1) among the ancient Greeks the cult name of the goddess Persephone.

2) In ancient Greek art there is a statue of an upright girl wearing long robes.

KUROS- in the art of ancient Greek archaism

- a statue of a young athlete (usually naked).

Kouros

Kouros sculptures

The height of the statue is up to 3 meters;

They embodied the ideal of male beauty,

strength and health;

The figure of an upright young man with

foot forward, hands clenched

into fists and extended along the body.

Faces lack individuality;

Exhibited in public places, in

close to temples;

Bark

Sculptures

They embodied sophistication and sophistication;

The poses are monotonous and static;

Chitons and cloaks with beautiful patterns from

parallel wavy lines and a border along

edges;

Hair is curled and tied back

tiaras.

There's a mysterious smile on your face

1. Hymn to the greatness and spiritual power of Man;

2. Favorite image - a slender young man with an athletic build;

3. Spiritual and physical appearance are harmonious, there is nothing superfluous, “nothing in excess.”

Sculptor Polykleitos. Doryphoros (5th century BC)

CHIASM,

in the visual arts

art image

worth human

figure leaning on

one leg: in this case, if

the right shoulder is raised, then

the right hip is dropped, and

vice versa.

Ideal proportions of the human body:

The head makes up 1/7 of the total height;

Face and hands 1/10 part

Foot – 1/6 part

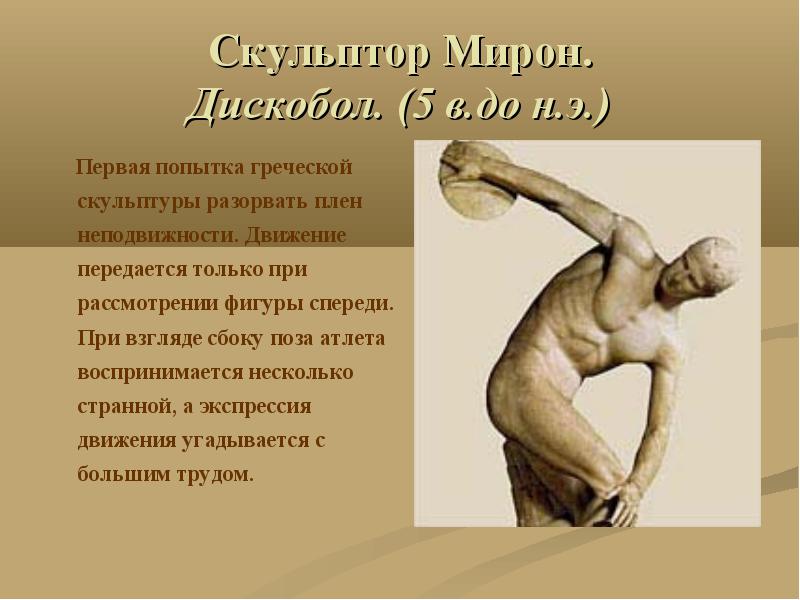

Sculptor Miron. Discus thrower. (5th century BC)

The first attempt of Greek sculpture to break the captivity of immobility. Movement is conveyed only when viewing the figure from the front. When viewed from the side, the athlete’s pose is perceived as somewhat strange, and the expression of the movement is difficult to discern.

IV century BC.

IV century BC.

1. We strived to convey energetic actions;

2. Conveyed the feelings and experiences of a person:

- passion

- sadness

- daydreaming

- falling in love

- fury

- despair

- suffering

- grief

Scopas (420-355 BC)

Skopas.

Maenad. 4th century BC. Skopas.

Head of a wounded warrior.

Skopas.

Skopas.

Battle of the Greeks and Amazons .

Relief detail from the Halicarnassus Mausoleum.

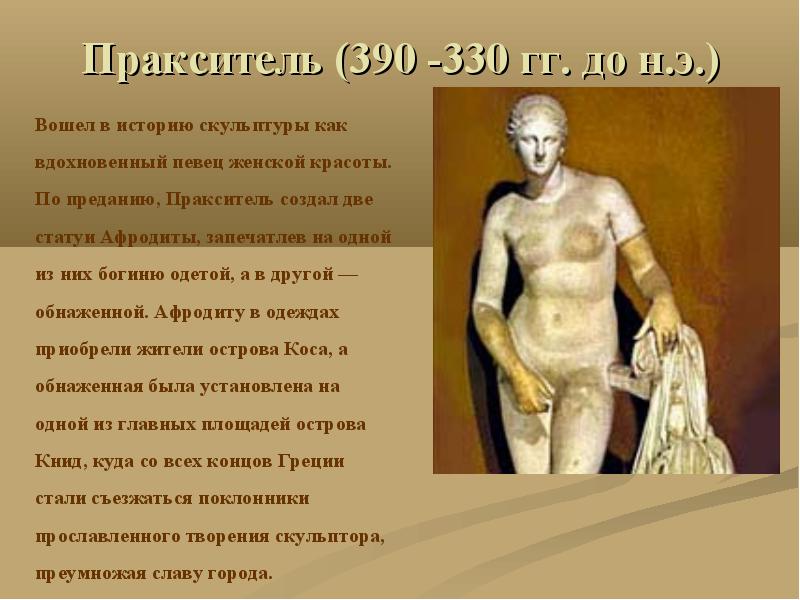

Praxiteles (390 -330 BC)

Entered the history of sculpture as

an inspired singer of female beauty.

According to legend, Praxiteles created two

statues of Aphrodite, depicting on one

one of them is a dressed goddess, and in the other -

naked. Aphrodite in robes

acquired by the inhabitants of the island of Kos, and

nude was installed on

one of the main squares of the island

Knidos, where from all over Greece

fans began to arrive

the famous creation of the sculptor,

increasing the glory of the city.

Lysippos.

Lysippos.

Alexander's head

Macedonian Around 330 BC

Lysippos.

Lysippos.

"Resting Hermes"

2nd half of 4th century. BC e.

Leohar

Leohar.

"Apollo Belvedere".

Mid 4th century BC e.

HELLENISM

HELLENISM, a period in the history of the countries of the Eastern Mediterranean from the time of the campaigns of Alexander the Great (334-323 BC) until the conquest of these countries by Rome, which ended in 30 BC. e. subjugation of Egypt.

In sculpture:

1. Excitement and tension in faces;

2. A whirlwind of feelings and experiences in images;

3. Dreaminess of images;

4. Harmonic perfection and solemnity

Nike of Samothrace. Beginning of 2nd century BC. Louvre, Paris

At the hour of my night delirium

You appear before my eyes -

Samothrace Victory

With arms extended forward.

Scaring away the silence of the night,

Causes dizziness

Your winged, blind,

Unstoppable desire.

In your insanely bright

glance

Something is laughing, flaming,

And our shadows rush behind us,

I can't keep up with them.

Agessandr. Venus (Aphrodite) de Milo. 120 BC Marble.

Agessandr. "The Death of Laocoon and His Sons." Marble. Around 50 BC e.

Crossword

Horizontally : 1. The person at the head of the monarchy (general name for kings, kings, emperors, etc.). 2. In Greek mythology: a titan holding the vault of heaven on his shoulders as punishment for fighting the gods. 3. Self-name of a Greek. 4. Ancient Greek sculptor, author of the "Head of Athena", a statue of Athena in the Parthenon. 5. A design or pattern made of multi-colored pebbles or pieces of glass fastened together. 6. In Greek mythology: god of fire, patron of blacksmiths. 7..Market Square in Athens. 8. In Greek mythology: the god of viticulture and winemaking. 9. Ancient Greek poet, author of the poems “Iliad” and “Odyssey”. 10. “Place for spectacles”, where tragedies and comedies were staged.

Vertically : 11. A person who has the gift of speech. 12.Peninsula in the southeast of Central Greece, territory of the Athenian state. 13. In Greek mythology: sea creatures in the form of a bird with a woman’s head, luring sailors by singing. 14. The main work of Herodotus. 15. In ancient Greek mythology: a one-eyed giant. 16. Drawing on wet plaster with paints. 17. Ancient Greek god of trade. 18. The author of the sculpture “Venus de Milo”? 19. Author of the sculpture “Apollo Belvedere”.