Greek sculpture briefly. Sculpture of Greece from the classical era - sculpture of ancient Greece. In the discipline "Russian and foreign art"

Greek sculpture from the classical period

The fifth century in the history of Greek sculpture of the classical period can be called a “step forward”. The development of sculpture in Ancient Greece in this period is associated with the names of such famous masters as Myron, Polyclene and Phidias. In their creations, the images become more realistic, if one can say, even “living,” and the schematism that was characteristic of archaic sculpture decreases. But the main “heroes” remain the gods and “ideal” people.

The idea of observing and explaining the universe was evident in the writings of Greek philosophers and more prominent in the chisel marks of sculptors of the classical period of Greece. It is also no coincidence that during the same period, society in Ancient Greece was organized around democratic principles, with city officials elected by demons who reserved the right to revoke their authority when they ceased to perform in front of demonstrations of "sympathy."

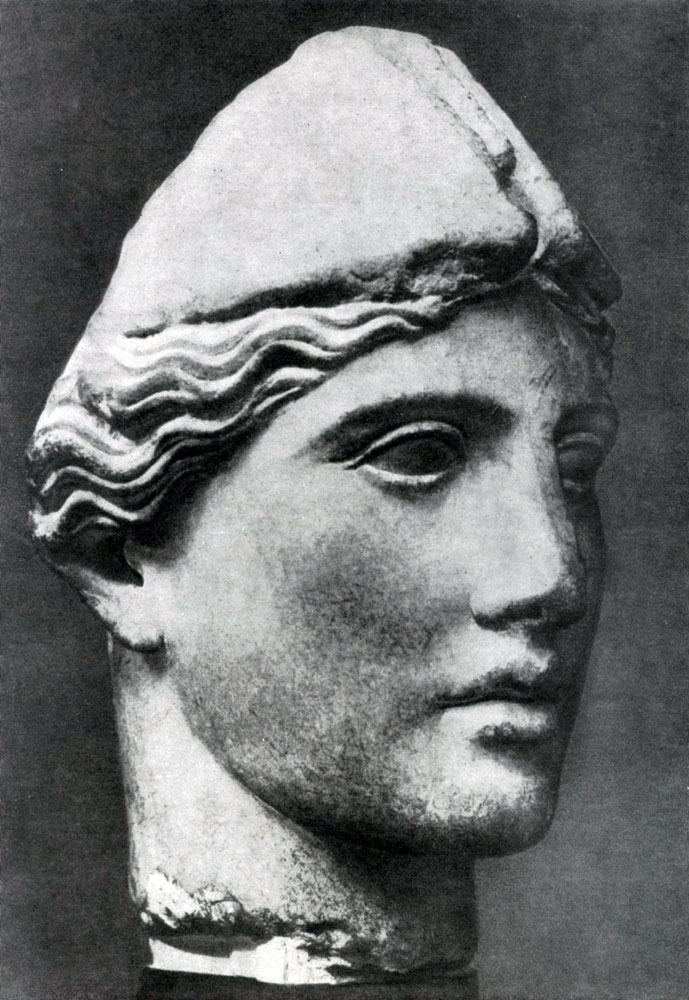

In the art of Greece during the classical period, the characteristic smile of archaic sculpture was replaced by a solemn expression. Even in sculptures depicting cruel and passionate scenes, the faces do not betray any expression. This applies only to the noble Greeks, because in the same sculptural groups the enemies are always depicted with dramatic facial expressions. The reason for this is that the ancient Greeks believed that suppressing emotions was a noble characteristic for all civilized people, while public display of human emotions was a sign of barbarism.

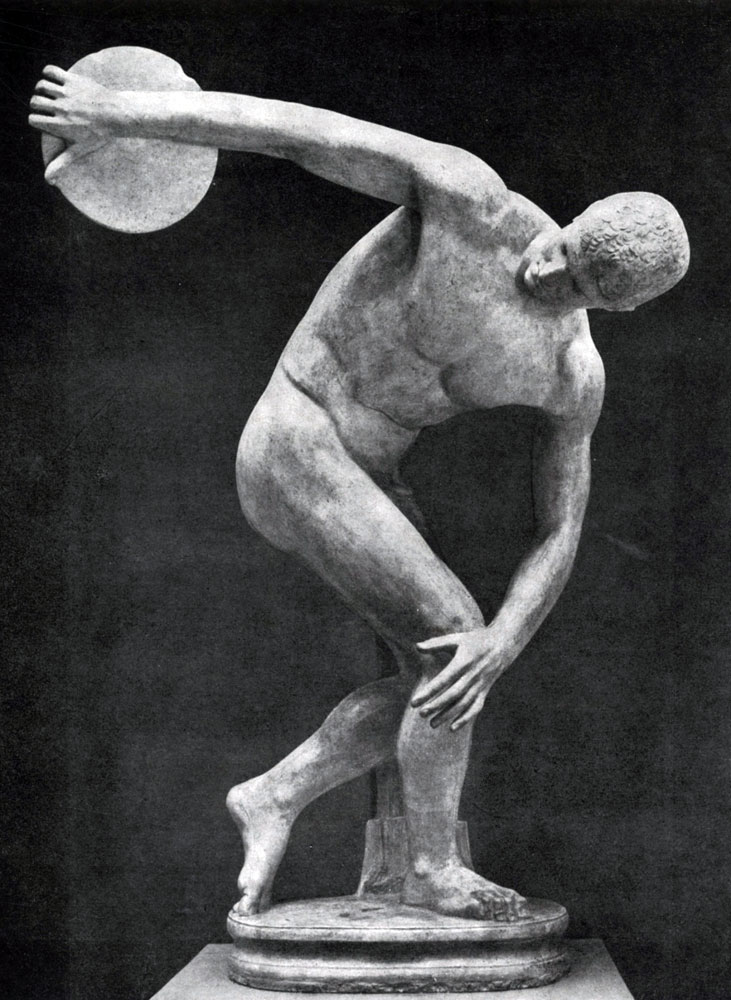

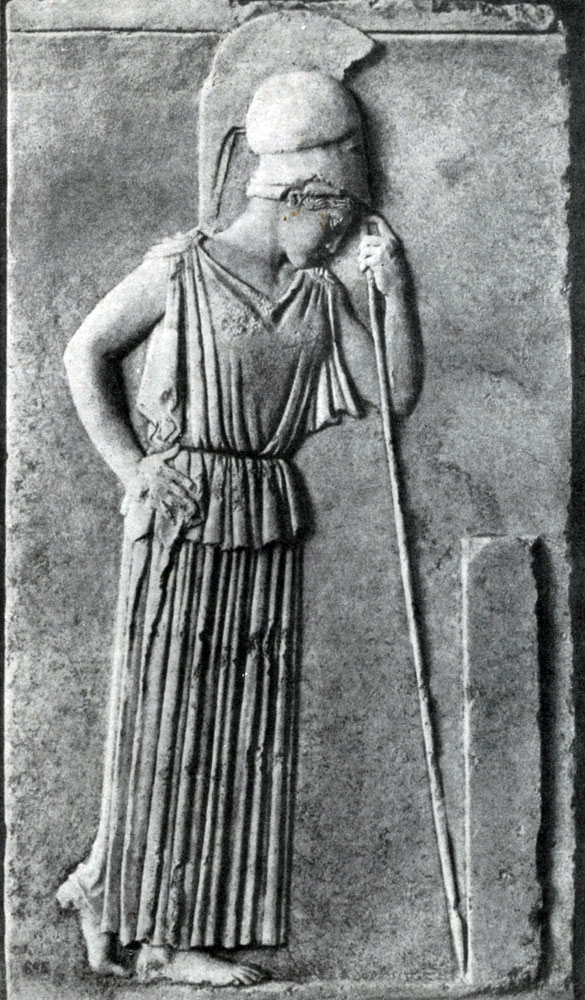

Miron, who lived in the mid-5th century. BC e, known to us from drawings and Roman copies. This brilliant master had an excellent command of plasticity and anatomy, clearly conveying freedom of movement in his works (ʼʼDiscoballʼʼ). His work “Athena and Marsyas” is also known, which was created on the basis of the myth about these two characters. According to legend, Athena invented the flute, but while playing she noticed how ugly the expression on her face changed; in anger, she threw the instrument and cursed everyone who would play it. The forest deity Marsyas was watching her all the time, and was afraid of the curse. The sculptor tried to show the struggle of two opposites: calm in the face of Athena and savagery in the face of Marsyas. Modern art connoisseurs still admire his work and his animal sculptures. For example, about 20 epigrams on a bronze statue from Athens have been preserved.

Logic and reason were expected to dominate human expression even in the most dramatic situations. In Ancient Greece, the concept of dialectics began to take shape. The world came to be understood as a series of opposing forces that created a certain synthesis and transitional balance that was always shifting to accommodate the movement of opposing forces. Thus, in sculpture, the human figure was understood as a universe of opposing forces that created a perfect aesthetic entity at the moment of achieving balance.

Like upper body weight. Shifted to one side, the corresponding leg muscles stiffened and the bones straightened to support him, while another group of muscles and bones on the other side relaxed and moved to maintain physical balance.

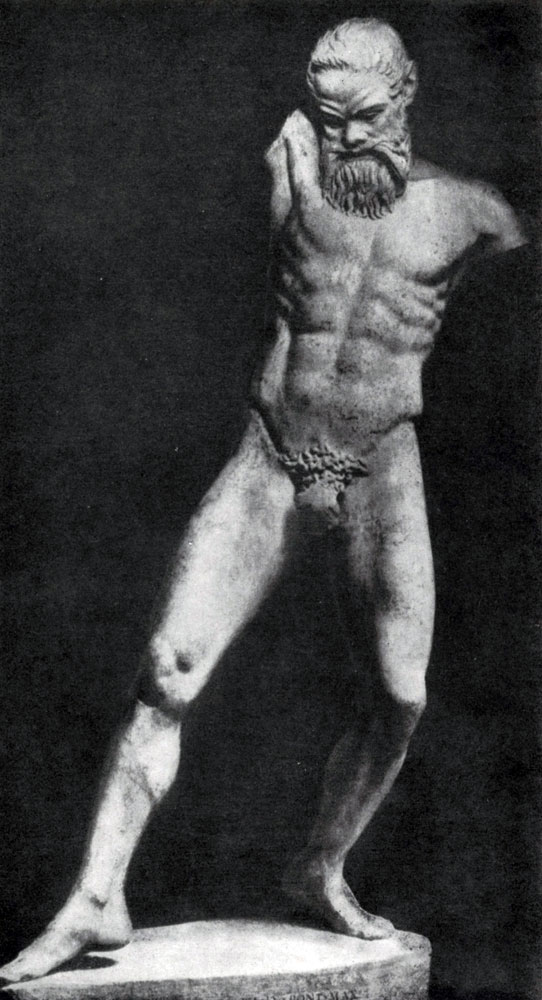

Polykleitos, who worked in Argos, in the second half of the 5th century. BC e, is a prominent representative of the Peloponnesian school. The sculpture of the classical period is rich in his masterpieces. He was a master of bronze sculpture and an excellent art theorist. Polykleitos preferred to portray athletes, in whom ordinary people always saw an ideal. Among his works are the famous statues of "Doryphoros" and "Diadumen". The first work is a strong warrior with a spear, the embodiment of calm dignity. The second is a slender young man with a competition winner's bandage on his head.

It was clear to the artist of the classical period of Greece that the beauty of everything depends on the harmony of its constituent parts and that each part depends on the others to create a harmonious group. Proportion became a major concern of sculptors and architects in ancient Greece, thus shifting attention to metaphysical subjects and to the formal problems of creating art and representing the world around us. The Greeks looked for relationships in the universal that created a harmonious balance, completely opposite.

The ancient Greek artist reinvented his self and became the creator of god and man alike in a universe of perfect formal proportions, idealized aesthetic values and a newfound sense of freedom. It was freedom from barbarity and tyranny and a transition to self-determination. More than any other art form, the sculptures of Greece are the pure expression of freedom, self-awareness and self-determination. These were the values that motivated the people of Ancient Greece to defeat mighty Persia and led them to develop a model of society that would ensure the dignity of every person within it.

Phidias is another prominent representative of the creator of sculpture of the classical period. His name resounded brightly during the heyday of Greek classical art. His most famous sculptures were the colossal statues of Athena Parthenos and Zeus in the Olympic Temple made of wood, gold and ivory, and Athena Promachos, made of bronze and located on the square of the Acropolis of Athens. These masterpieces of art are irretrievably lost. Only descriptions and small Roman copies give us a faint idea of the magnificence of these monumental sculptures.

The sculptor in this context became the creator of human values and used his deities as a pretext for creating humanity in stone and bronze. It became everyone's record of a man and his journey to self-determination. Decimation of population, reduction Agriculture led to nomadic life in Greece. This nomadic development led to cultural decline: the simple, unadorned architectural style and the art of writing were lost. That's why one speaks of a "dark time."

Once again, a hierarchical system was created and with colonization west coast Asia Minor, with the discovery of iron processing and the outgrowth of agriculture, a new economic boom began. This era is characterized by the merging of small settlements from which Poles later emerged. The era was named after examples of new ceramics and vase painting. The adoption of the Phoenician alphabet, to which the Greeks added the missing vowels, also declined at this time.

Athena Parthenos, a striking sculpture from the classical period, was built in the Parthenon Temple. It had a 12-meter wooden base, the body of the goddess was covered with ivory plates, and the clothes and weapons themselves were made of gold. The approximate weight of the sculpture is two thousand kilograms. Surprisingly, the gold pieces were removed and weighed again every four years, since they were the gold fund of the state. Phidias decorated the shield and pedestal with reliefs on which he depicted himself and Pericles in battle with the Amazons. For this he was accused of sacrilege and sent to prison, where he died.

Archaic art is considered the pioneer of the later classical period. Poetry, tragedy, prose and scientific-rational thinking of the Pre-Socratics are developing. In architecture, the direction returns to the monumental. A significant stylistic device of archaic art was the so-called archaic smile.

The period of classical art is marked by the Peloponnesian War and Athenian democracy. This time is also called the golden age. Sacred art is becoming increasingly important in architecture - it creates huge temple buildings. In plastic, movement and internal unity of the composition of the image are increasingly expressed.

The statue of Zeus is another masterpiece of sculpture from the classical period. Its height is fourteen meters. The statue depicts the supreme Greek deity seated with the goddess Nike in his hand. The statue of Zeus, according to many art historians, is greatest creation Fidia. It was built using the same technique as when creating the statue of Athena Parthenos. The figure was made of wood, depicted naked to the waist and covered with ivory plates, and the clothes were covered with gold sheets. Zeus sat on the throne and in his right hand he held the figure of the goddess of victory Nike, and in his left there was a rod, which was a symbol of power. The ancient Greeks perceived the statue of Zeus as another wonder of the world.

Hellenistic art develops from a fusion of Greek and Oriental culture. There are themes related to reality. From greek sculpture several works have been preserved. Most of the items that have been studied are Roman copies, which must be of lower quality.

If Greek paintings disappeared because of the fragility of their supports, the case of Greek sculpture is different because the favored materials for important works were durable: stone and bronze. In addition to the outright destruction of pagan works by Christians, the materials of the works were recycled in the Middle Ages: crushed marble to produce lime and cast bronze.

Athena Promachos (circa 460 BC), a 9-meter bronze sculpture of ancient Greece, was built right among the ruins after the Persians destroyed the Acropolis. Phidias “gives birth” to a completely different Athena - in the form of a warrior, an important and strict protector of her city. She has a powerful spear in her right hand, a shield in her left, and a helmet on her head. Athena in this image represented the military power of Athens. This sculpture of ancient Greece seemed to reign over the city, and everyone who traveled by sea along the shores could contemplate the top of the spear and the crest of the statue’s helmet sparkling in the rays of the sun, covered in gold. In addition to the sculptures of Zeus and Athena, Phidias creates bronze images of other gods using the chrysoelephantine technique, and takes part in sculpting competitions. He was also the leader of large construction works, for example, the construction of the Acropolis.

Characteristics of Greek Sculpture

Its maximum representation is archaic statues male and female stereotypes. Although idealization is a constant in Greek art in favor of clarity and beauty, this tendency will be more noticeable for the natural and gradual enhancement of realistic effect and specific characterization. Surface human knowledge improves how different parts of the body are articulated, and the influence of stresses caused by movement and expression.

Knowledge that would not be surpassed until the Renaissance. The classical aesthetic for the male body first and for the female one develops later, proposing a new convention in proportions and introducing canons of seven and eight heads for human figures. The aegynetic smile characteristic of archaic Greek sculpture is replaced by a slightly wrinkled frown, that serious gesture of classical serenity, which would be imitated or replaced by drama and dramatization in accordance with other later Hellenistic schools.

Greek sculpture of the classical period - concept and types. Classification and features of the category "Greek sculpture of the classical period" 2014, 2015.

The heroic era of the Greco-Persian wars and the years immediately following them were a time of rapid growth of slave-holding policies. In the fight against the Persians they proved their vitality and strength and subsequently entered the time of their greatest power. A period of extensive construction of public architectural structures began, the creation of monumental sculpture and frescoes, which asserted the strength and significance of the Greek city-states, the dignity, greatness and beauty of man. A decisive turning point occurred in the development of art.

Frontality and symmetry are disrupted by new points of view, the hidden movement of figures in tension, the first explorations of contrapposto that balance a more relaxed pose and the inclusion of new alternative positions in standing sculptures. Fabrics will gradually gain independence from figures, mutating regularity and archaic monotony with the optical effects of realism and the emphasis of anatomical forms or the dynamism of the subject.

Materials and techniques of Greek sculpture

In Ancient Greece, many reliefs were carved on tombstones, voting boards and architectural decoration, the latter being considered the most high quality. These reliefs were previously carved from stone using metal tools. Lost wax bronze was the preferred method of creating public statues, but marble, limestone and terracotta were also used.

The features of archaic conventions still made themselves felt for some time in vase painting and especially in sculpture. But these were now only relics of an archaic tradition that were quickly fading into the past. All Greek art during the first third of the 5th century. BC. was permeated with an intense search for methods of realistic depiction of a person, primarily the truthful transmission of movement, as well as the creation of a natural group composition, free from the principles of decorative symmetry. In vase painting, and then in sculpture and monumental painting, realism won. The range of topics and subjects has expanded dramatically. The synthesis of sculpture and architecture began to be understood as a free community and complementarity of equal and valuable arts.

Criselephantine statues made of marble and gold were scarce due to their high cost and were reserved for the most significant cult statues. This was applied to stone sculptures, especially limestone works for a rougher finish, beginning with decorative designs and becoming more restrained and naturalistic during the development of Greek art.

In addition to these materials, wood, bone and ivory were also used in miniatures. The increase in the number of private commissions and the need to spread Greek culture to new settlements during the Hellenistic period promote the creation of examples of works of art and the specialization of artisans, promoting the use of new conventions, monumentality and the loss of technical quality.

Monumental and public character of architecture Greek classics, its close connection with the life of a collective of free citizens, with the state cults of the gods who personified the unity of the polis, found their bright and strong expression already in the period of the early classics.

The Doric order played a leading role at this time. The advanced features of Greek architecture of the previous, archaic period have now received wide and free development. The deep correspondence of the entire figurative structure of the Doric order with the spirit of civil heroism of the 5th century. BC. especially helped to reveal all the artistic possibilities inherent in it.

The main themes of Greek sculpture were.

- Gods and mythological scenes.

- Heroes and battles.

- Olympic athletes will win.

The spread of Greek art over an increasingly wider area also provoked the creation of art schools with their own identification marks.

- School of Athens: classical models and portraits.

- The School of Alexandria: Everyday Life and Allegories.

- School of Pergamon: drama and pathos.

- Rhodes School: Dramatic Themes and Forced Bodies.

The peripterus became the dominant building type in Greek monumental architecture. The classical type of peripter and the entire system of its proportions received their development precisely in these years.

In terms of their proportions, the temples became less elongated, more integral; the disproportion and heaviness of archaic architectural proportions were overcome in them. In big temples interior space- naos - usually divided into three parts by two longitudinal rows of columns. In small churches, architects did without internal columns supporting the ceiling of the pump. The use of colonnades with an odd number of columns on the end facades, which interfered with the location of the entrance to the temple in the center of the facade, has disappeared. The usual ratio of the number of columns of the end and side facades became 6 to 13 or 8 to 17; the number of columns on the side was equal to twice the number of columns on the end façade plus one column.

Characteristics of Classical Greek Sculpture

Fragment of the Frisian Parthenon, an example of classical Greek sculpture. It is known as the stage after archaic sculpture and before. Perhaps the most significant change in classical sculpture in relation to the archaic is the change in poses, which become increasingly natural and therefore less rigid. Changes in this direction, such as the use of oblique views or the rotation of bodies, occur first in bas-reliefs and then in statues.

It was during this classical period that contrapposto was invented, a more relaxed pose for standing statues in which the weight of the body rests on one straight leg, which causes the hips and shoulders to tilt in opposite directions. In these drawings, the previous composition of a vertical line begins to be replaced by a double curve to represent the axis of the body. This twist will also be applied to the head of statues, less in cults, to avoid acquired innateness.

In the depths of the central part of the naos, framed by internal colonnades, directly opposite the entrance there was a statue of the deity. The layout of the temple received a logically clear harmony and monumental solemnity. A strictly thought-out system of arrangement and correlation of all elements of the temple’s structure led to the creation of a majestic, clear and simple image.

There has been great progress in surface knowledge. The sculptors are interested in the tension that occurs in the male body of athletes in motion. However, the gesture on the faces of these statues in movement remains unchanged with the serene expression characteristic of sculptures of this era.

Although the representation of anatomy appears to be becoming more correct, it remains an idealized version of the beauty of the human body rather than a realistic copy. The desire to find and define the ideal perfection of perfect mathematics leads to the creation and monitoring of the canon of Platonic proportions.

The architects of the early classics subtly felt the connection between the system of proportions of architectural forms and the absolute scale of the building and its size relative to man and the surrounding landscape. The development of a permanent system of parts of the order and their form occurred simultaneously with an increasingly free and diverse construction of their proportional relationships. Minor changes in proportions caused corresponding changes in the balance of the carried and load-bearing parts. By modifying the proportions of all parts of the building, the Architects modified the entire character of its figurative expressiveness. Therefore, each temple of the classical period combined the principles of a canonical solution developed over centuries of experience with aspects specific to this particular temple. This gave it individual originality and made it a unique work of art. This also achieved the solution to the problem of the relationship of the temple with the environment and determined its very character, sometimes powerful and majestic, sometimes light and graceful.

This feature of Greek architecture is characteristic of the entire structure of ancient Greek artistic consciousness. For example, Greek tragedy also developed in the traditional and strict forms of theatrical canons. At the same time, for the same playwright, for example Aeschylus or Sophocles, in each drama, in accordance with the nature of the conflict depicted and with the figurative structure of this drama, the ratio of the prologue, epilogue, choral parts, the construction of the poetic speech of the main characters, etc. was significantly modified.

The monument transitional from late archaic to early classic was built around 490 BC. Temple of Athena Aphaia on the island of Aegina. Its dimensions are small. The ratio of the columns is 6 to 12. The columns are slender in proportion, but the entablature is still prohibitively heavy. The temple was built of limestone and covered with painted plaster. The pediments were decorated with sculptural groups made of marble (now located in the Munich Glyptothek). The location of the temple at the top of a high coastal slope clearly shows how Greek architects knew how to connect strict Doric architecture with the surrounding natural space.

Temple “E” in Selinunte (Sicily) also had a transitional character. It differed from the temple on the island of Aegina by its excessively elongated proportions (the ratio of the columns was 6 to 15). Its columns are squat and often spaced; the entablature is very high, its height almost equal to half the height of the column. In general, with its heavy power, it resembles temples of the 6th century. BC, although the processing of details and the division of forms are distinguished by greater clarity and rigor of execution.

The typical features of early classical architecture were most fully embodied in the temple of Poseidon in Paestum (Great Greece) and in the temple of Zeus in Olympia (Peloponnese).

![]()

Temple of Poseidon at Paestum, built in the second quarter of the 5th century. BC, well preserved. Full of austere grandeur, powerful and somewhat heavy, it rises on a three-step base. The low stylobate and low but wide steps emphasize the impression of calm, balanced strength. The columns (ratio 6 to 14; see the drawing with the plan of the Temple of Poseidon in Paestum) are relatively massive; strong entasis creates a feeling of elastic tension in the column, as if lifting the ceiling with force. The entire colonnade juts out against the background of a shadowed space; deep horizontal shadows from the far protruding abaci fall on the columns, emphasizing the line of collision between the load-bearing and borne parts. All the main elements of the architectural composition are clearly expressed, architectural details only reveal the main relationships of the architectural structure, and this also enhances the impression of concentrated power.

The temple was designed to be perceived from different distances. From a distance, the temple with its relatively low columns seems somewhat smaller than in reality, and at the same time very compact and strict in form. Up close, the large size of the columns compared to a person becomes clear and the overall dimensions of the temple become noticeable; details (including flutes that are more frequent than usual), becoming clearly visible, highlight the massive proportions and size of the building. The contrast of impressions from distant and close points of view contributes to the growing feeling of strength and grandeur of the entire structure as it approaches. This technique of comparing several points of view is extremely characteristic of the principles of classical architecture. The Greek architect of the classical era always sought to create an architectural image that was oriented towards human perception, taking into account and organizing the path of movement of the viewer.

Temple of Zeus at Olympia, built between 468 and 456. BC. architect Libo, had the significance of a pan-Hellenic sanctuary and was the largest temple in the entire Poloponnese. The temple is almost completely destroyed, but based on excavations and descriptions of ancient authors, its general appearance can be fairly accurately reconstructed.

It was a classic Doric peripter (column ratio 6 to 13), built from solid limestone (shell rock), which made it possible to achieve almost hammered precision and purity of detail. The proportions of the temple were distinguished by severity and clarity. Their severity was softened by a festive nature. The temple was decorated with large sculptural groups on the pediments. The metopes of the outer frieze, as in most early classical temples, were devoid of sculptural decoration. 3a, in the outer colonnade above the porticoes of the pronaos and opisthodome, sculptural compositions were placed on the metopes of the triglyph frieze, six on each frieze. The subjects of these reliefs were closely related to the public purpose of the temple, which was the center of the vast architectural ensemble of Olympia - the sacred center of pan-Hellenic sports competitions. The legendary chariot race of Pelops and Oenomaus and the battle of the Greeks (Lapiths) with the centaurs were depicted on the pediments, and the labors of Hercules were depicted on the metopes. Inside the temple from the middle of the 5th century. BC. there was a statue of Zeus made of gold and ivory by Phidias.

Thus, in the temple of Zeus at Olympia, the characteristic classical Greece the synthesis of architecture and sculpture, which will be discussed in detail later, when describing the Parthenon, and the principles of architectural classics were finally approved.

A very important part of Greek art in the classical period was vase painting, in which classical realism gave its vivid expression.

The heyday of the city-state was also the heyday of artistic crafts of various types of applied and decorative arts. Ceramics decorated with highly artistic painting continued to hold a leading place among them.

Vase painting was imbued with the traditions of folk artistic craft with its sense of the artistic value of every thing created by human creative labor. Although the best vases, made by the largest and leading artists, were for the most part intended for cult offerings or served to decorate festive feasts, it was still the living and constant connection with the folk art of master potters and master draftsmen that determined their high artistic perfection.

During the period of the early classics, the realistic tendencies of the advanced vase painters of the late archaic period received rapid and profound development, becoming dominant already during the years of the Greco-Persian wars. At this time, the red-figure technique finally replaced the black-figure technique. It made it possible to realistically depict volume and movement, construct any angles, and naturally and freely model the human body.

The artistic worldview of the classics, based on a deep interest in the surrounding life and in the real person, quickly expanded the range of possibilities of realistic depiction contained in the red-figure technique. Instead of the flat silhouette of black-figure vase painting, artists began to build three-dimensional bodies, taken in the most diverse and lively turns and angles. This free and convincing transmission of movement, far from the conventional play of black spots and lines scratched on black varnish, was complemented by the greater naturalness of the reddish color of the clay, which was now used to depict human figures, since it was incomparably closer to the idea of a tanned naked body than shiny black varnish color. The black lines of the drawing on a light clay background now conveyed the muscles and details of the body, allowing a realistic reproduction of the structure of the human body and its movement. This gave a powerful impetus to the development of the art of drawing.

The masters of red-figure vase painting sought not only to specifically depict the human body and movement - they came to a new, realistic understanding of composition, constantly drawing complex scenes of mythological and everyday content. In some respects, the development of vase painting outstripped the development of sculpture. In vase painting there are many realistic discoveries similar to those in sculpture of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC, appeared already in last years 6th century and in the first decades of the 5th century. BC, that is, in the period after the reforms of Cleisthenes and during the war.

The composition of vase paintings of the early classics became more and more complete and holistic; it was naturally limited to the inner surface of a flat bowl or the side surface between the handles of the vase. Within the boundaries of the surface of the vase allocated for the composition, vase painters, with exceptional freedom and observation, conveyed a wide variety of scenes Everyday life, as well as the heroic events of myths and Homeric epic. Traditional mythical stories were reinterpreted, imbued with new motifs drawn from life.

The most prominent vase painting masters of this time were Euphronius, Duris and Brig, who worked in Athens. All of them were characterized by a desire for naturalness in the image. But the degree of novelty, that is, liberation from archaic conventions and the conquest of realistic freedom, was not the same among them.

The eldest of these masters, Euphronius (who worked at the very end of the 6th century BC; later he became the owner of a workshop where other draftsmen worked), was most associated with archaic patterning and ornamentation.

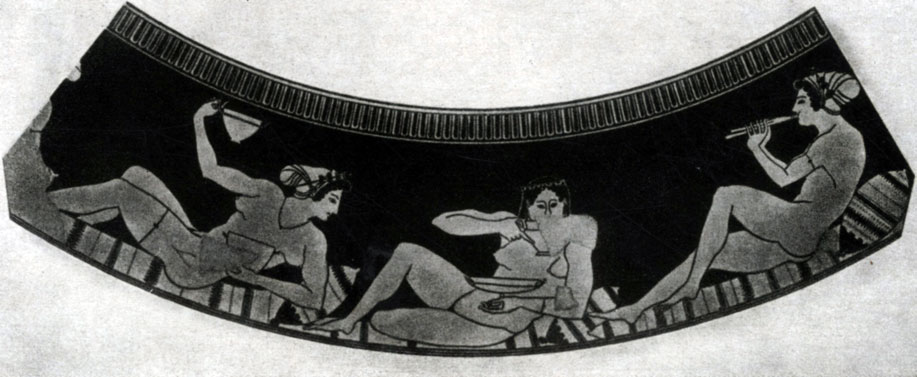

In vases painted by Euphronius, with the image of Theseus at Amphitrite or hetaeras playing kottab, the desire for too free and complex perspectives and movements, in the absence of a yet developed method of realistic drawing, led to the conventional flatness of some details; Purely decorative elements also occupy a lot of space in Euphronius: patterns on clothes, etc.

Later, in the first quarter of the 5th century. BC. masters learned to find such artistic means of depicting movement that could, without destroying the integrity of the surface of the vessel, give a feeling of three-dimensional spatiality of the drawing, and this led to the final overcoming of the archaic principle of flatness of the image. True, vase painting throughout the 5th century. BC. She operated mainly with graphic means of depiction, without pursuing actual pictorial tasks (for example, the transfer of light and shade). For some time, all that remained of the archaic were elements of elegance, a sophisticated linear outline, which to some extent still played a purely decorative role. It is precisely these echoes of archaic art that are found in some of the works of Duris, one of the most remarkable draftsmen of the early classics.

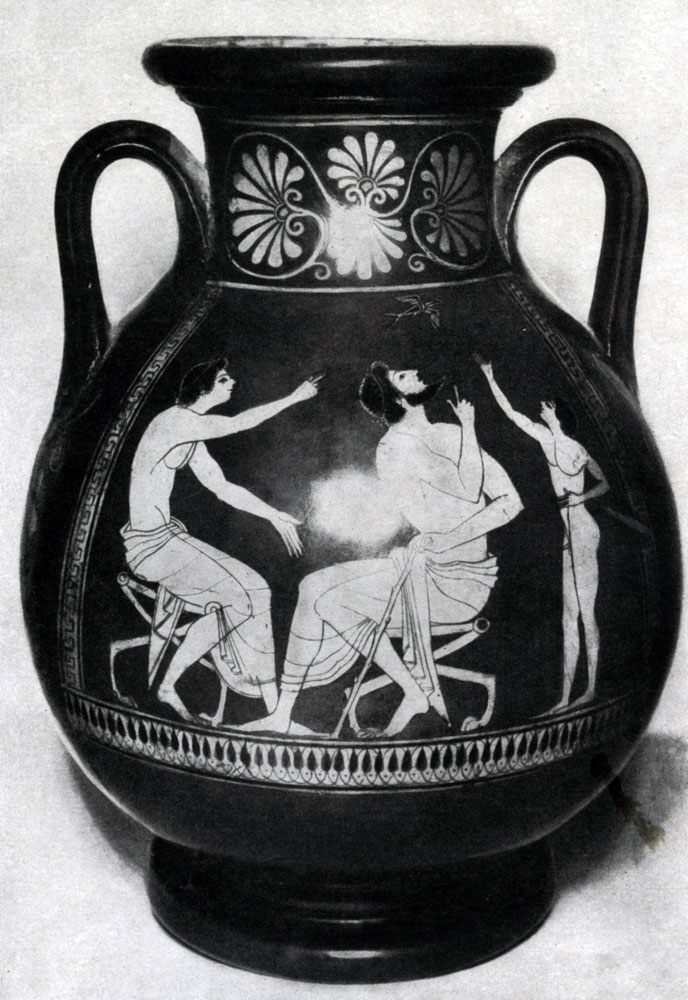

In the vases, the drawings of which were made by Duris, one can feel the dependence of his artistic techniques on the nature of the plot; more elegance and ornamental rhythm in drawings on mythological themes (“Eos with the body of Memnon”), more simplicity and relaxed freedom in drawings on themes of everyday life (“School Scene”). The ease and virtuosity of the artist’s construction of any complex pose, any real gesture (for example, in the image of a sitting teacher) is amazing.

Closer to the beginning of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC. Compositions that consciously set the task of an organic connection between a vitally natural image and the form and rhythmic structure of the vessel become more numerous and more perfect. Masters of vase painting began to understand more and more clearly that the architectural beauty of the forms of a vessel should never be destroyed by the image, that their close connection should serve to their mutual benefit. This is the design by Brig (about 480 BC) decorating the bottom of a wine cup kept in the Würzburg Museum. By the way, the very theme of the last drawing is directly related to the purpose of the vessel: a kind-hearted girl supports the bowed head of a young man who has abused wine. The owner of the cup, draining it, had the opportunity to contemplate at its bottom this playful reminder of the need to know the measure of all things. The two standing figures are perfectly inscribed in the round bottom of the bowl, and at the same time they are distinguished by an extremely bold and simple construction of the three-dimensional form. A deep respect for the value and beauty of real human life enabled Brig to imbue even such a prosaic topic with genuine grace.

Brig was a bold pioneer of new paths, and his discoveries played a vital role in the formation of the realistic principles of the classics. Compared to Euphronius, Brig took a big step forward in his work. His drawings, very diverse in themes, genre and mythological, are not only distinguished by vital spontaneity and natural simplicity, but also solve many problems of dramatic construction of action. His vase dedicated to the Trojan War is distinguished by the genuine pathos of the depiction of the battle, which reminded Brig’s contemporaries of the events of the Greco-Persian Wars.

The lesser dependence of vase painters on the constraining archaic tradition and their direct connection with artistic craft led to the fact that the realistic nature of the artistic culture of the early classics was reflected in vase painting not only earlier, but also in a broader appeal to everyday life than could have been the case in monumental sculpture. One can even assume that the masters of monumental sculpture used the experience of advanced vase painting masters, who at the beginning of the 5th century. BC. were ahead of sculptors precisely in the field of conveying human action and movement.

The image of a sculptor’s workshop on a bowl by an unknown master from the 480s is very interesting, full of deep seriousness and respect for work. True, this shows an artistic craft that is more respected due to the significance of its products. The work of the sculptor is described in great detail and accurately: craftsmen work around the bronze casting furnace, the finished statue is mounted, tools and bronze reliefs are hung. But the setting is given only by these objects - the artist does not depict the walls on which they hang: in vase painting, as in sculpture or monumental painting, the environment surrounding a person was not interested in the artist, who showed only people - their actions, expressive meaningfulness, the appropriateness of their movements and actions. Even the tools with which a person acts, and the fruits of his labor, were shown only so that the meaning of the action was clear - things, like nature, occupied the artist only in their relation to man. This explains the absence of landscape in Greek vase painting - both early and high classics. Man's attitude to nature, to its forces and phenomena was conveyed through the image of the man himself, through his reaction to natural phenomena.

Thus, the lyrics of the coming spring are embodied in a red-figure “vase (pelik) with a swallow” (late 6th - early 5th century BC; State Hermitage Museum) in the image of a boy, youth and adult who saw the messenger of spring - a flying swallow. Three figures, different in their build and in their poses, are connected by one action and form an integral and living group. The common feeling that unites these people looking up at the swallow is expressed in the inscriptions that accompany each figure and are linked in a short dialogue. The young man who was the first to see the swallow says: “Look, swallow”; his senior interlocutor confirms: “It’s true, I swear by Hercules”; the boy exclaims joyfully, concluding the conversation: “Here it is - spring already!”

In the second quarter of the 5th century. BC. Greek vase painting acquires a previously unprecedented strict and clear harmony, but at the same time it to some extent loses that direct sharpness and brightness that distinguished the works of the first vase painters of classical art - Duris or Brig. But the vase painting of this time, as well as monumental painting, is more appropriate to consider together with the art of the Age of Pericles - the art of high classics.

In the northern part of the Peloponnese, in the Argive-Sicyon school, the most significant of the Doric schools, the sculpture of the emerging classics developed mainly the task of creating a calmly standing human figure. Deeply reworking the old Doric traditions in the light of new artistic goals, the largest master of the school Agelad already at the beginning of the 5th century. BC. sought to solve the problem of reviving a calmly standing figure. Shifting the center of gravity of the body to one leg allowed Agelad and other masters of this school to achieve the free naturalness of the pose and gesture of the human figure. The consistent development by Argive-Sicyon masters of a well-thought-out system of proportions, revealing the real beauty of the perfect human body, was also of great importance.

The Ionic movement, in the same desire to master the vital persuasiveness of the image of a person, followed its own path, in accordance with its old traditions. The masters of the Ionic movement paid especially much attention to the depiction of the human body in motion.

However, the difference between these two directions in the classical period was not significant. The advanced masters of both directions, although they followed different paths, had a common goal - the creation of a realistic image of a perfect person. Already in the 6th century. BC. the Attic school synthesized the best aspects of both directions: by the middle of the 5th century. BC. it most consistently established the basic principles of advanced realistic art associated with the heyday of Athens, and acquired the significance of the leading pan-Hellenic center of art. Main city Attica - Athens - by the middle of the 5th century. BC. collected and united the best artistic forces of Hellas to create monuments and architectural structures that praised the dignity and beauty of the Athenian, and with it, the entire Greek people (or rather, the free citizens of the Greek city-states).

An important feature of Greek sculpture of the classical period was its inextricable connection with public life, which was reflected both in the nature of the image and in its place in the city square.

Greek sculpture of the classical period was of a public nature; it was the property of the entire collective of free citizens. It is natural, therefore, that the development of the social and educational role of art, the revelation of a new aesthetic ideal in it, was most fully reflected in monumental sculptural works associated with architecture or standing in squares. But at the same time, it was in such works that the deep disruption of the entire structure of artistic principles that accompanied the transition from archaic to classic was reflected with particular clarity. The new social ideas of victorious democracy came into sharp conflict with the conventionality and abstraction of archaic sculpture.

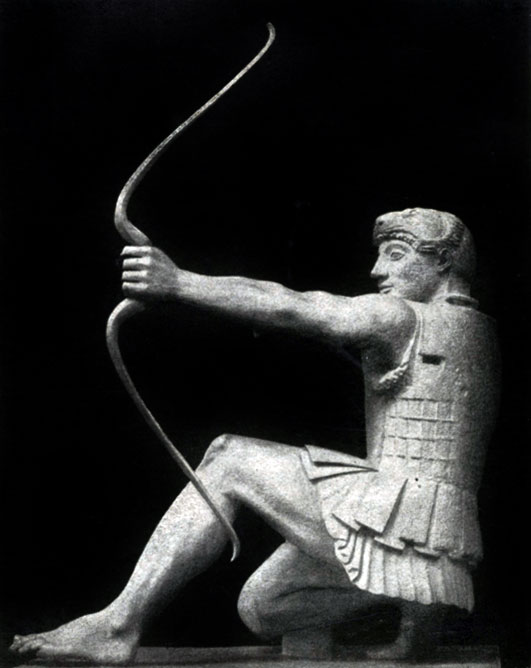

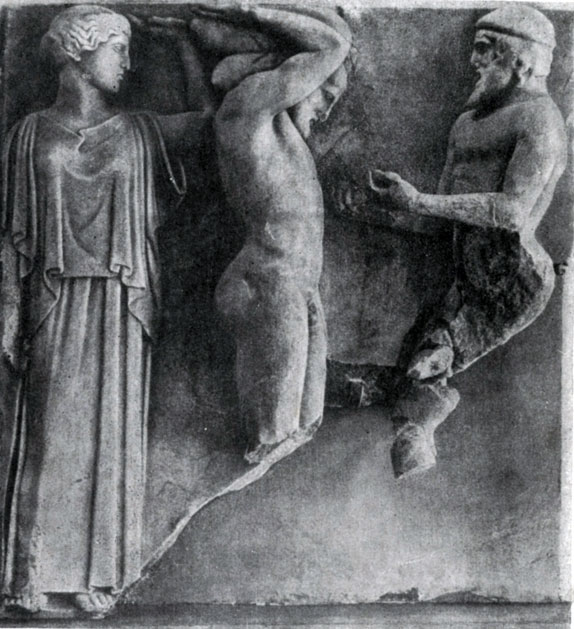

The contradictory, transitional nature of some sculptural works of the early 5th century. BC. clearly appears in the pediment groups of the Temple of Athena Aphaia on the island of Aegina (circa 490 BC).

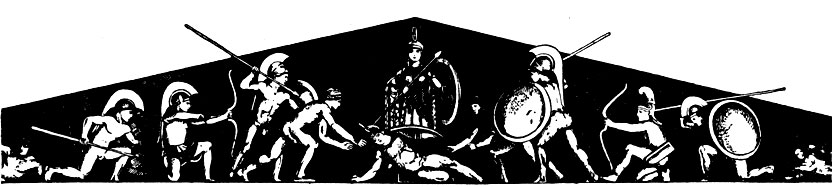

The pediment sculptures of the Aegina Temple were found at the beginning of the 19th century. in a severely damaged state and then restored by the famous Danish sculptor Thorvaldsen. One of the most likely options for reconstructing the composition of the pediments was proposed by the Russian scientist V. Malmberg. The composition of both pediments was built on the basis of strict mirror symmetry, which to some extent imparted ornamental features to the painted sculptural groups protruding against the colored background of the pediments.

The western pediment depicted the struggle between the Greeks and Trojans for the body of Patroclus. In the center was the motionless, strictly frontal figure of Athena, as if deployed on the plane of the pediment, dispassionately calm and as if invisibly present in the midst of the battle. Her participation in the ongoing struggle is shown only by the fact that her shield is facing the Trojans and her feet are turned in the same direction. Only from these symbolic hints can one guess that Athena acts as the protector of the Hellenes. Apart from the figure of Paris in a high curved helmet and with a bow in his hands, it would be impossible to distinguish the Greeks from their enemies, so much so are the figures mirrored on the left and right half of the pediment.

Nevertheless, in the figures of warriors there is no longer archaic frontality, their movements are more real, their anatomical structure is more correct than was usually the case in archaic art. Although the entire movement unfolds strictly along the plane of the pediment, it is quite vital and concrete in each individual figure. But on the faces of the fighting warriors and even the wounded, the same conventional “archaic smile” is given - a clear sign of connectedness and convention, poorly compatible with the image of intensely fighting heroes.

The Aegina pediments still reflected the constraining rigidity of the old archaic canons. Compositional unity was achieved by external, decorative methods; the very principle of combining architecture and sculpture was here, in essence, still archaic.

True, already in the eastern pediment of the Aegina Temple (preserved much worse than the western one) an undoubted step forward was made. A comparison of the figures of Hercules from the eastern pediment and Paris from the western pediment clearly shows the great freedom and truthfulness in the depiction of a person by the master of the eastern pediment. The movements of the figures here are less subordinate to the plane of the architectural background, more natural and free. Particularly instructive is the comparison of the statues of wounded warriors on both pediments. The master of the eastern pediment has already seen the inconsistency of the “archaic smile” with the state in which the warrior finds himself.

The motive of the movement of the wounded warrior is recreated in strict accordance with the truth of life. To some extent, the sculptor mastered here not only the transfer of external signs of movement, but also the depiction through this movement of the internal state of a person: vital forces slowly leave the athletically built body of a wounded warrior, the hand with a sword, on which the reclining warrior leans, slowly bends, his legs slide along the ground , no longer giving reliable support to the body, the powerful torso gradually falls lower and lower. The rhythm of the bowing body is emphasized by contrast with a vertically placed shield.

Mastering the complex and contradictory richness of movements of the human body, which directly conveys not only the physical, but also the mental state of a person, is one of the most important tasks of classical sculpture. The statue of a wounded warrior from the eastern pediment of the Temple of Aegina was one of the first attempts to solve this problem.

For the destruction of the constraining conventions of archaic art, the appearance of sculptural works dedicated to specific historical events, which clearly embodied the social and moral ideals of the victorious slave-owning democracy, was of exceptional importance. Given their relative small number, they were a particularly striking sign of the growth of the social, educational, civic content of art, and its realistic orientation.

The mythological theme and plot continued to dominate in Greek art, but the cult and fantastically fairy-tale side of the myth receded into the second Alan and almost disappeared. The ethical side of myth has now come to the fore, the revelation in mythological images of the power and beauty of the ethical and aesthetic ideal of modern Greek society, the figurative embodiment of the ideological tasks that concern it. A realistic rethinking of mythological images, leading to the reflection of modern ideas in them, was carried out by Greek artists of the classical period, as well as by the great Greek tragedians of the 5th century. BC. - Aeschylus and Sophocles.

Under these conditions, the emergence of individual works of art that directly address facts real story, although sometimes taking on a mythological connotation, was deeply natural. Thus, Aeschylus created the tragedy “The Persians,” dedicated to the heroic struggle of the Greeks for freedom.

The sculptors Critias and Nesiot created it in the early 470s BC. a bronze group of Tyrannicides - Harmodius and Aristogeiton - in place of the archaic sculpture depicting the same heroes taken away by the Persians. For the Greeks of the 5th century. BC. images of Harmodius and Aristogeiton, who killed in 514 BC. the Athenian tyrant Hipparchus and those who died were an example of the selfless valor of citizens who were ready to give their lives to defend civil liberties and laws hometown(In reality, Harmodius and Aristogeiton were guided by the interests not of the democratic, but of the aristocratic party of Athens in the 6th century. BC, but in this case it is important for us how the Athenians of the 5th century imagined their social role. BC.). The composition of the group, which has not survived to this day, can be restored from ancient Roman marble copies.

In “Harmody and Aristogeiton,” for the first time in the history of monumental sculpture, the task of constructing a sculptural group united by a single action and a single plot was set. Indeed, for example, the archaic sculpture “Cleobis and Biton” by Polymedes of Argos can be considered only conditionally as a single group - essentially these are just two statues of kouros standing next to each other, where the relationship of the heroes was not depicted. Harmodius and Aristogeiton are united by a common action - they strike the enemy. The movement of figures made separately and placed at an angle to each other converges at one point where an imaginary opponent stands. The unified direction of the movement and gestures of the figures (in particular, the hand of Harmodius raised to strike) creates the necessary impression of the artistic integrity of the group, its compositional and plot completeness, although it should be emphasized that this movement is generally interpreted very schematically. The faces of the heroes were also devoid of expression.

According to the information that has come down to us in ancient Greek sources, the leading masters who determined the decisive turn in sculpture in the 70s - 60s. 5th century BC. to realism, there were Ageladus, Pythagoras of Rhegium, Calamis. An idea of their work can to some extent be gleaned from Roman copies from greek statues this time, and most importantly, according to a number of surviving authentic Greek statues of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC, made by unknown masters. A general picture of the development of Greek sculpture until the mid-5th century. BC. can be imagined with sufficient clarity.

The concept of Greek art of the 70s - 60s. 5th century BC. They also produce small bronze figurines that have survived to this day. Their significance is especially great because the bronze Greek originals, with rare exceptions, have been lost and they have to be judged from far from accurate and dry Roman marble copies. Meanwhile, specifically for the 5th century. BC. characterized by the widespread use of bronze as a material for monumental sculptures.

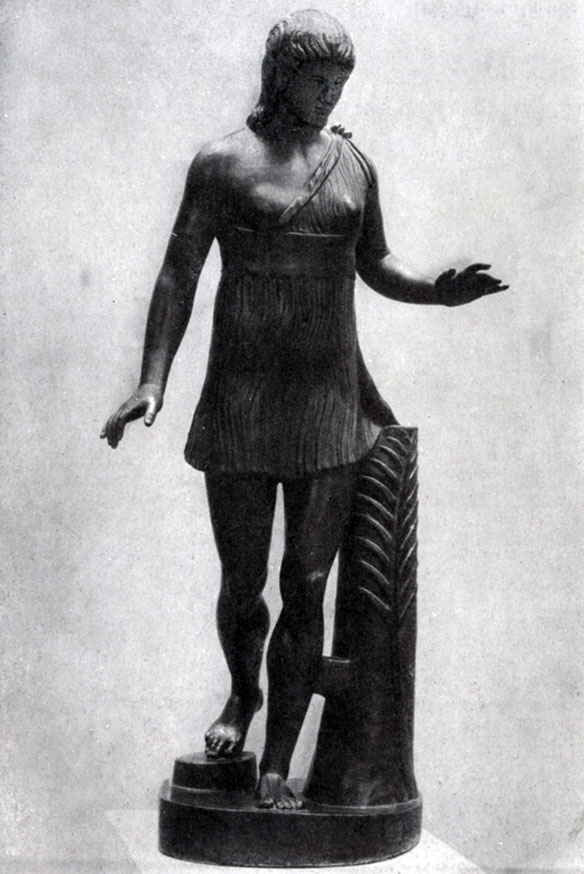

One of the most consistent innovators of the initial period of the early classics was, apparently, Pythagoras of Rhegium. The main goal of his work was a realistic depiction of man in natural life movement. Thus, according to the description of the ancients, his statue “Wounded Philoctetes” is known, which amazed contemporaries with its truthful depiction of human movements. The statue “Hyacinth” or (as it was previously called) “Eros Soranzo” is attributed to Pythagoras of Rhegium (State Hermitage, Roman copy). The master depicted the young man at the moment when he follows the flight of the disk thrown by Apollo; he raised his head, the weight of his body was transferred to one leg. The depiction of a person in a holistic and unified movement is the main artistic task that the artist set for himself, who decisively rejected the archaic principles of a strictly frontal and motionless statue, consistently and deeply developing the features of realism accumulated in the art of the late archaic. At the same time, the movements of “Hyacinth” are still somewhat sharp and angular; some stylistic features, for example in the treatment of hair, are directly related to archaic traditions. In this statue, new artistic tasks are boldly and sharply set, but a harmonious and consistent system of a new artistic language corresponding to these tasks has not yet been fully created.

Realistic vitality, the inextricable fusion of philosophical and aesthetic principles in the artistic image, the heroic typification of the image of a real person - these are the main features of the emerging art of the classics. The social and educational significance of the art of the early classics was inextricably and naturally fused with its artistic charm; it was devoid of any elements of deliberate moralizing. A new understanding of the tasks of art was reflected in a new understanding of the human image, in a new criterion of beauty.

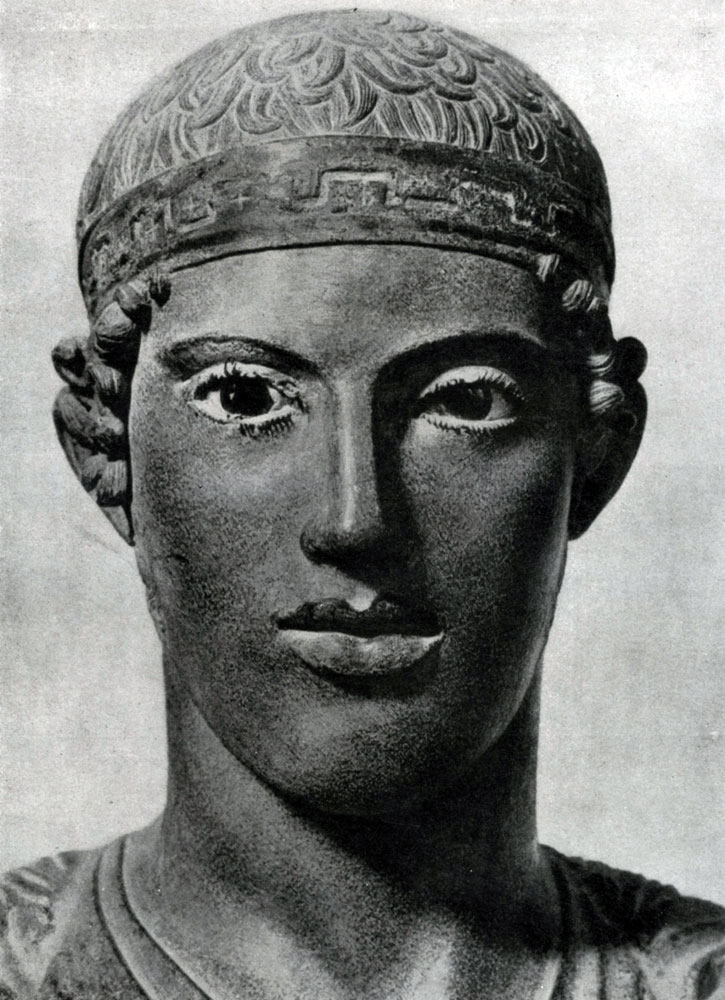

The birth of a new aesthetic ideal is revealed especially clearly in the image of the “Delphic Charioteer” (second quarter of the 5th century BC). The “Delphic Charioteer” is one of the few authentic ancient Greek bronze statues that have come down to us. It was part of a large sculptural group that has not reached us, created by a Peloponnesian master close to Pythagoras of Rhegium. Severe simplicity, calm greatness of spirit are poured throughout the entire figure of the charioteer, dressed in long clothes and standing in a strictly motionless and at the same time natural and living pose. The realism of this statue lies primarily in the sense of significance and beauty of a person that permeates the entire figure. The image of the winner in the competition is presented in a generalized and simple manner, and although individual details are made with great care, they are subordinated to the overall strict and clear structure of the statue. In “The Delphic Charioteer,” the characteristic classical idea of sculpture was already expressed in a fairly defined form, as a harmonious and vitally convincing depiction of the typical features of a perfect person, shown as every free-born Hellene should be.

The same realistic typification of the image of a person was completely transferred by the masters of the early classics to the images of gods. "Apollo from Pompeii", which is a Roman replica of a Greek (Northern Peloponnesian) statue of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC, differs from the archaic “Apollos” not only in the incomparably more realistic modeling of body shapes, but also in a completely different principle of the compositional solution of the figure. The entire weight of the body is transferred here to one left leg, the right leg is slightly moved to the side and forward, a slight turn is given to the shoulders in relation to the hips, the head is slightly tilted to the side; the hands of a beautiful young man, as the god of the sun and poetry is depicted here, are given in free and relaxed movement. At first glance, these seemingly minor changes during that period of accumulation of realistic means were in fact extremely important: every change in artistic techniques that led away from the archaic was not just a technical innovation, but an expression of new features in the worldview.

In such statues the conventional frontal composition and the equally conventional constraint of archaic statues were completely overcome. Although already at the end of the 6th and the very beginning of the 5th century. BC. A number of masters tried to rework the design of the archaic kouros statue in this direction, but the artists were able to successfully solve the problem of depicting a natural, organically integral movement only after profound changes in the entire artistic worldview - in the years after the victory in the Greco-Persian wars.

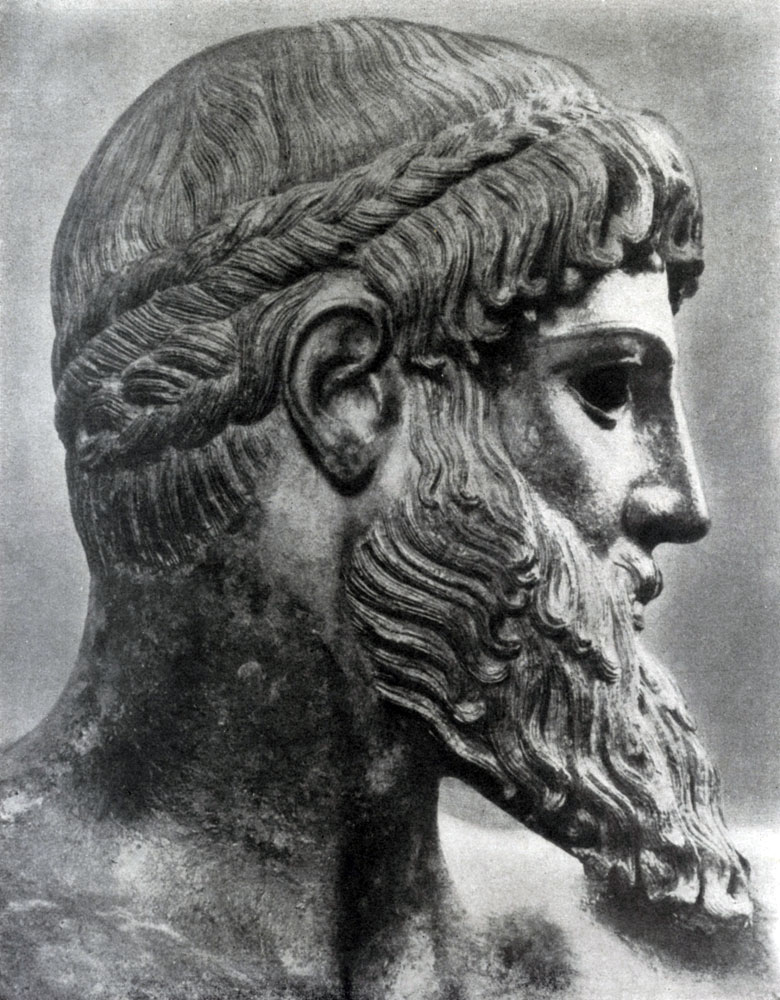

The heroic character of the aesthetic ideals of the early classics was perfectly embodied in the bronze statue of “Zeus the Thunderer,” found in 1928 at the bottom of the sea off the coast of the island of Euboea. This large statue (more than 2 m high), along with the “Delphic Charioteer,” gives us a clear idea of the remarkable skill of the sculptors of the early classics. “Zeus the Thunderer,” compared to “Arioteer,” is distinguished by even greater realism in the modeling of body shapes and greater freedom in conveying movement. Widely spaced, slightly bent legs give elasticity to the rapid step of the figure. Undoubtedly, the wide span of Zeus’s arms (which reached only in fragments), full of majestic power, was undoubtedly magnificent, raising his right hand far back with a lightning bolt clutched in it, which in a moment he would throw at an enemy invisible to us, in whose direction his inspired face was turned. The muscles of the powerful torso are tense. The play of light reflections on the dark bronze undoubtedly further emphasized the strong sculpting of the forms. In the statue of “Zeus the Thunderer,” the task of expressing the general mental state of the hero in sculpture was well solved. This bronze statue of Zeus may be close in character to the work of Ageladus, a master who created a number of statues famous in antiquity, in which he (judging by the descriptions of the ancients) took the most important step towards improving the realistic representation of the human body in movement or in rest, full of restrained revival.

The development of early classical sculpture in the direction of increasing realism is also evidenced by the statue of “A Boy Taking out a Splinter,” which has come down to us in a marble Roman copy from a bronze original of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC. The boy’s figurine is distinguished by a natural, angular pose and a realistic representation of the body shape of a teenager. Only the hair, as if not subject to gravity, is given somewhat conditionally. Vital observation here is reminiscent of scenes full of realism in vase paintings of this time. However, this is not just a genre sculpture. The statue tells the story of a teenager who became famous for his valor during a running race. A sharp thorn pierced his leg, but the boy continued running and was the first to reach his goal.

A great success in depicting real movement and at the same time in creating a realistically truthful and typical image was the appearance of such statues as the “Winner in the Run”. In place of the angular sharpness of "Hyacinth" and other early classical statues a strict harmonious unity came, conveying the impression of naturalness and freedom. Dressed in a short chiton, with her right breast exposed, the girl is depicted at the moment of finishing her run. The impression of slowing running is achieved by a slight movement of slender legs, a subtle turn of the shoulders, and arms pulled to the sides. The statue was made of bronze; the Roman copyist, who repeated it in marble, added a rough support.

Artists of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC. did not know complex internal characteristics. But, depicting the real appearance of a person and his actions, they invariably conveyed the entire structure of his spiritual life and character.

Thus, despite some sharpness and angularity of the movement deployed in one plane, the remarkable statue of the “Wounded Niobide”, stored in the Museum of Baths in Rome, is distinguished by its undoubted drama. This statue may have been part of a pediment group that has not reached us.

The task of depicting the human body in all its vital naturalness was also posed in the statues “Nereids from Xanthus”, made by an Ionian master around the middle of the 5th century. BC. “Nereids” decorated the “Monument of the Nereids” in Asia Minor. Echoes of the archaic scheme of “kneeling running” are still noticeable in the interpretation of these figures (the legs, given in profile, do not quite correspond to the position of the upper body). However, the “Nereids” are distinguished by their unusually lively modeling of the body, which is facilitated by the grace of the thin, seemingly flowing folds of their clothes.

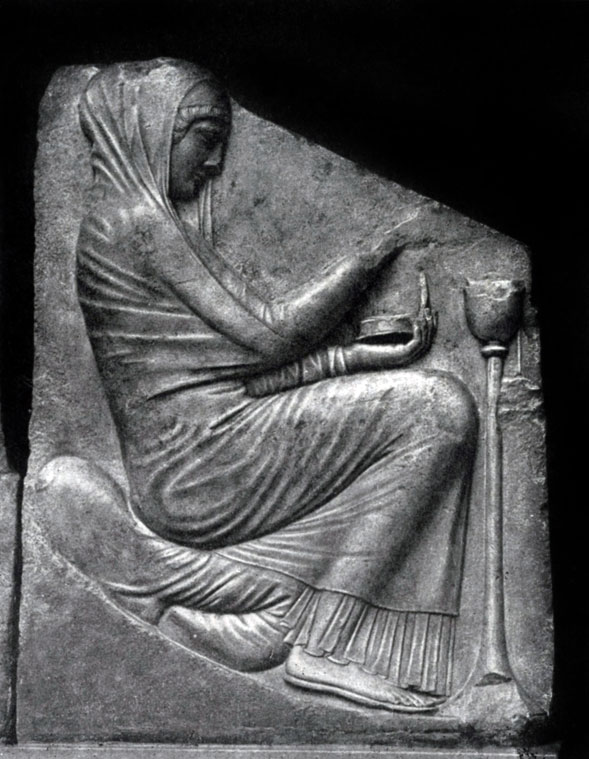

A striking example of the rethinking of familiar mythological subjects during the years of radical disruption of archaic traditions and the emergence of classical art is a remarkable relief, probably also executed by an Ionian master of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC. and depicting the birth of Aphrodite from the foam of the sea (the so-called “Throne of Ludovisi”); On the sides of this marble "throne" or rather pedestal for the statue of Aphrodite are depicted a naked girl playing a flute and a woman dressed in a long robe in front of an incense burner. Clear and simple harmony, calm naturalness of the movements of the figures and the realistic vitality of their grouping sharply distinguish these works from archaic reliefs.

On the central of the three sides of the “Throne of Ludovisi” there are two nymphs, bending over, supporting Aphrodite emerging from the waves; The calm rhythm of the movements of the rising Aphrodite and the straightening nymphs corresponds to the rhythm of the thin folds of their clothes. The wet peplos covering Aphrodite's body covers her with a thin network of wavy lines, like streams of water. The sea pebbles on which the nymphs’ feet rest indicate the location of the action. Although the strict symmetry of the composition contains echoes of archaic art, they can no longer disturb the realistic vitality of this relief.

Depicted on either side of the central group, a seated naked girl playing a flute and a woman wrapped in a cloak offering incense to the gods are compositionally almost identical to each other. However, the entire group is far from the purely decorative ornamental symmetry of the archaic composition. The figures are three-dimensional and three-dimensional, they are given in natural and free poses. The seated girl leaned back at ease. One of her legs is crossed over the other, which especially emphasizes the real spatiality of the relief. Her figure is full of grace. Fingers glide easily and quickly over the flute. The pose of a sitting young woman - wife and mother, keeper of the home - is stricter, more motionless, the movement of her hands is calm and measured. Both of these figures, in their differences embodying different aspects of beauty and love, are, as it were, united by the image of Aphrodite, under whose power they are equally under and different aspects of whose service they both embody. From a mechanical combination of figures that had an abstract symbolic character, art turned to a holistic, organic and living artistic image, in which basic ethical and aesthetic ideas were embodied.

Thus, Greek sculpture of the early classics by the 50s. 5th century BC. has come an extremely long way of development. The next important step towards high classics was the pediment groups and metopes of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia (50s of the 5th century BC).

The general style of the Olympic sculptures is already approaching the style of Myron’s sculptures. Pausanias attributes the authorship of the sculptures of the pediments of the Temple of Zeus to Paeonius of Mende and Alkamen the Elder, but confirmation of this has not yet been found. In any case, the authors of these sculptures were first-class artists.

The eastern pediment is dedicated to the myth of the competition between Pelops and Oenomaus, which laid the foundation for the Olympic Games, while the western pediment is dedicated to the battle of the Lapiths with the centaurs. Both pediments differ sharply from the pediments of the Aegina Temple with their decorative conventional composition. The masters of the Olympic pediments understood the sculptural group primarily as a depiction of a real event. The arrangement of the figures is determined primarily by the meaning of the event, by the participation in the event that is characteristic of each figure. The balance of the composition in this case contributed to the strict clarity and integrity of the story. The statues of the Olympic Temple are remarkable for their genuine realism. It is no coincidence that they opened in the 70s. 19th century The sculptures of Olympia caused a certain disappointment among archaeologists and art historians of that time, who imagined the art of the 5th century. BC. as a kind of “ideal” and “harmonious” art and “shocked” by the harsh power of realism and the “roughness” of the images of these wonderful monuments, which worthily completed the period of realistic quests of the early classics.

Having abandoned the complete subordination of the sculptural image to the tasks of decorating architectural forms, the sculptors of the Olympic pediments established other and deeper connections between the architectural and sculptural images, which led to their equality and their mutual enrichment and found their most consistent expression a quarter of a century later in the Parthenon built under the leadership of Phidias.

The myth to which the eastern pediment of the Temple of Zeus is dedicated boils down to the following. King Oenomaus was predicted to die at the hands of the husband of his daughter Hippodamia. To avoid this fate, Oenomaus, who owned fabulously fast horses, announced that the one who defeated him in a chariot race would receive his daughter’s hand. The defeated one had to give up his life, and many suitors were killed by the cruel and treacherous Oenomaus. Finally, Pelops, with the help of cunning, managed to defeat Oenomaus: the charioteer Oenomaus, who had bribed him, removed the pin from the chariot axle and replaced it with one made of wax. Oenomaus fell to his death during the competition. The eastern pediment of the Temple of Zeus depicts the heroes before the start of the competition. The majestic figure of Zeus in the center of the pediment, the solemn peace that embraces all participants in the events, gives the pediment that strict and at the same time festive elation, which corresponds to the composition located above the main entrance to the temple. The absence of sudden movements and the almost symmetrical arrangement of the figures, however, do not lead to rigidity and immobility. This peace is apparent, it is full of internal tension.

Although the statues of the eastern pediment have survived to this day in a severely damaged state and their location has also not yet been finally established, the general nature of their poses and gestures can be represented with sufficient reliability. In any case, the five central figures - Zeus, Oenomaus, his wife Sterope, Pelops and Hippodamia - standing in calm poses, as if responding to the strict rhythm of the columns over which they rise, despite the symmetry of their arrangement, are very different and individual in their appearance and gestures .

One of the greatest achievements of classical art was that it was able, unlike art Ancient East, to show the role and significance of each person in his relationships with other people, to present him not as an impersonal component particle dissolving in the general, often ornamental structure of any multi-figure composition, but precisely as a personality, as a conscious participant in the general action, occupying a clear position in it and a specific place. In the Olympic pediments many important aspects of this achievement of classical art were first discovered.

On the sides of the central group on the eastern pediment there were chariots with horses, servants, spectators, and in the corners of the pediment there were reclining figures personifying local rivers. Some of these statues are distinguished by a particularly sharply emphasized realistic truthfulness - for example, the decrepit body of a sitting old man or the rude gesture of a boy pulling out a splinter are carefully depicted. One might even think that the master who created this pediment consciously sought to emphasize his break with the old principles of archaic convention, showing that in his figurative thinking he comes from life, and not from a conventional scheme.

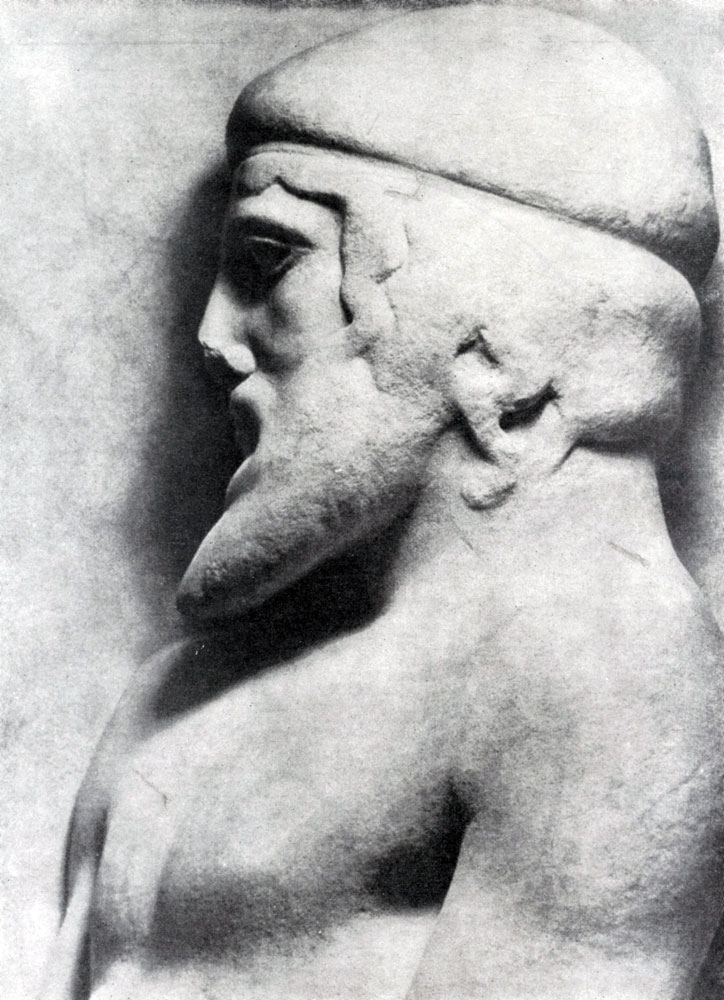

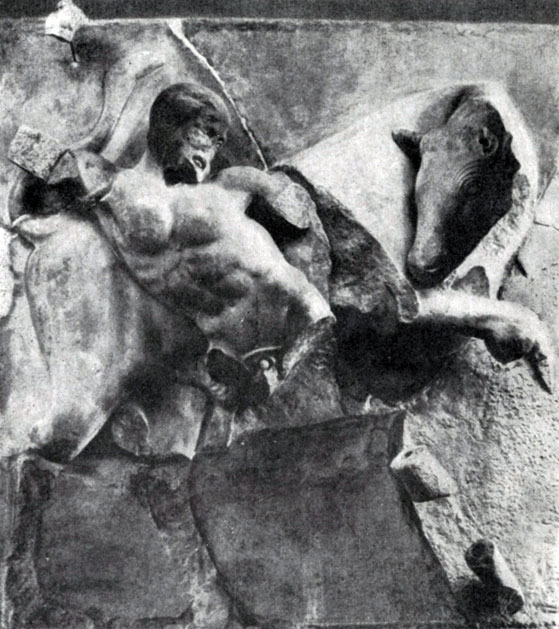

The realistic principles of the sculptors of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia were especially clearly revealed in the composition of the western pediment, depicting the battle of the Lapiths with the centaurs. This pediment arrived in a relatively less damaged state and caused less controversy regarding its reconstruction. It is especially valuable that many heads of statues, highly perfect in their execution, have been preserved here. The western pediment, as well as the eastern one, is characterized by a general compositional balance of both halves of the pediment, free from strict symmetry. This pediment, with a large statue of Apollo in the center, consists of a number of separate groups of fighting and wrestling men and centaurs; the groups are mutually balanced in terms of their total mass and intensity of movement, without repeating one another in any way. The figures of the fighters are precisely inscribed in the gentle triangle of the pediment, and the tension and sharpness of the movements increase towards the corners of the pediment - as they move away from the calmly standing figure of Apollo. His stern and clear face and the imperious, directing gesture with which he shows the Lapiths how to defeat the wild and violent centaurs serve as a kind of psychological and dramatic center of this entire complex and at the same time easily visible composition.

The central standing figures - Apollo, Theseus and Perithous - again, as I do in the east pediment, to some extent repeat the measured rhythm of the colonnade, thereby seeming to emphasize the calm strength and confidence that they bring to the tension of the battle. In action, in the heroic struggle against forces hostile to man, the spirit of masculinity and unity, which is embodied in the architecture of the Temple of Zeus, seems to be humanized.

The myth depicted in the pediment group tells how centaurs, half-humans, half-beasts, personifying the lower elemental forces of nature, who were invited to the wedding of the Lapithian king Perithous, rushed to kidnap the Lapithian women. Led by Theseus and Periphoes and inspired by the support of Apollo, the Lapiths exterminated the centaurs. Although the battle is shown in full swing on the pediment, the victory of the people is clearly predetermined. The images of Apollo, the bride of Perithos - Deidamia, or the woman grabbed by the hair by a centaur, created by an unknown artist, are among the most perfect and most attractive creations of early Greek classics. The struggle of human will and reason with the outbreak of elemental and unbridled forces - such is the heroic idea full of humanity that permeates this wonderful sculptural group. However, the difference between the Lapiths and the Centaurs is given here within the limits of general aesthetic norms; the laws of beauty also apply in the depiction of ugly centaurs, interpreted without any naturalistic emphasis.

The images on the metopes of the Temple of Zeus, dedicated to the exploits of Hercules, are close in spirit to the pediment compositions. The reliefs of the metopes are distinguished by their laconic simplicity and clarity of images, and the vivid expressiveness of the action. The arrangement of the figures on the metopes and the nature of their movement are closely related to the architecture, never violating the boundaries allocated to the relief by the architectural design. So in the metope depicting Hercules supporting the vault of heaven with the help of Athena, and Atlas carrying him the apples of the Hesperides ( According to myth, Hercules had to get golden apples from the Hesperides garden, located at the edge of the world. Hercules turned to Atlas, who supports the firmament, with a request to get him these apples. Atlas agreed on the condition that Hercules would hold up the firmament for him.), all the figures with their verticals repeat the verticals of the columns and triglyphs framing the metope. At the same time, the horizontal of the heavy cornice lying on the frieze is used to convey the feeling of the heaviness that Hercules carries; his hands, raised above his head, seem to support the structure of the cornice.

The metope dedicated to the fight of Hercules with the Cretan bull is very expressive. The intersecting, multi-directional movements of Hercules and the bull create a stable composition inscribed in the square of the metope; the movements of these figures coincide with the diagonals of the square and are thereby included in the general system of geometric relationships and proportions characteristic of an architectural structure. At the same time, the strict balance of the composition did not in the least prevent the sculptor from affirming the victory of man: the free and bold movement of Hercules is full of energy and swiftness, the strength and will of the hero triumphs over the power of the bull.

It was no coincidence that the effective and morally significant image of the folk hero Hercules appeared on the frieze of the Olympian Temple of Zeus, as well as the battle with the centaurs on its pediment. For the art of Greek classics, a real person with his living feelings and heroic deeds became the main theme.

The image of a citizen and a warrior, a man who harmoniously developed his physical and moral qualities, became central in the art of classics. However, human labor activity, living conditions, and connections with the environment were relatively little and rarely depicted in Greek monumental art of the classical period. The image of a person was revealed specifically, but social life was revealed only indirectly. For Greek classics, it was natural to express social conflicts and norms of behavior in fairy-tale and mythological images.

Realism of the classics of the 5th century. BC. distinguished by his own unique system of means of expression. Thus, body proportions and diverse forms of movement already in the early classics became the most important means of characterizing the general state of mind to which a given movement corresponded. This feature of classical art developed during the second quarter of the 5th century. BC, reaching full clarity in the sculptures of the Olympic Temple. The discovery of realistic content and artistic expressiveness of gesture was one of the greatest achievements of Greek classics, paving the way for a truly realistic depiction of man in all the truthfulness and integrity of his being.

Slower and with great difficulty, but also the person’s face in classical sculpture freed from that psychological rigidity and abstract impersonality that was characteristic of archaic Greek sculpture. Indeed, the face of the “Delphic Charioteer” is imbued with clear seriousness, the gaze of “Zeus the Thunderer” is stern and menacing, the faces of the fighting centaurs on the western pediment of the Olympic Temple are distorted with rage, the face of Apollo, and all his strict generality, expresses an imperious impulse, anger, tempered by volitional tension. But nowhere here is typical generalization combined with individualization of the image. The personal identity of a person, the unique character of his character, were far from being fully included in the circle of interests of the artists of the Greek classics. This side of the realistic disclosure of the image of a person was able to develop in full force in advanced art only after the turning point from the Middle Ages to modern times - in the Renaissance, in the 17th or 19th centuries.

The creation of a truthful and deeply significant typical image of man as a norm and model for every human citizen was of greater importance for Greek classics than the revelation of individual human character. This was the enormous strength and at the same time the limits of the realism of the Greek classics. Therefore, in the Olympic sculptures, very real and various mental states are of a generalized nature; they do not contain any complex or psychologically profound experiences.

Connected with this is the following feature of Greek sculpture and, in general, Greek fine art of the early and high classics: the person’s face has not yet taken place in relation to human body preemptive or exclusive right to transmit mental life. It is equally expressed throughout the body, in all its movements, including facial expressions.

This feature largely determined the unique nature of the development of portraiture in Greek classics. Initially, the most common type of portrait (according to its purpose) sculpture was the statue of the winner at the Olympic competitions. But the winner, from the point of view of the ancient Greeks, was awarded a statue because with his victory he asserted the glory of his native city, because he acted as a courageous and exemplary citizen, becoming a model for others. The statue of the winner was commissioned by the city-state to glorify the winner, but at the same time to glorify the city whose representative at the competition was the winner. Naturally, it was in this sense that he was portrayed as an artist. A valiant spirit in a harmoniously developed body - this was considered the most valuable thing in a person. But with these properties the Greek youth, participant olympic games, actually possessed. Therefore, probably, both the community and the winner himself were completely satisfied that his name stood on the pedestal on which a typically generalized beautiful statue stood.

The first portraits in the proper sense of the word, which were awarded to citizens who stood out for their services to the polis and were elected to one of the most honorable and responsible public positions, were also still devoid of a clearly defined individual characteristic. The portrait of a strategist (in the Munich Glyptotek) gives us an idea of the portrait of this period: the shape of the face is conveyed in a very generalized and simple manner, with stern expressiveness. The artist created the image of a statesman, calm and decisive, but this image does not convey the unique character traits of this particular person. And the signs of pronounced external resemblance were hardly of interest to the sculptor.

With the greatest force, the creative quest of the early classics, its search for heroic, typically generalized images, was expressed in the activities of the great Greek sculptor Myron from Eleuther. Myron worked in Athens at the end of the second and beginning of the third quarter of the 5th century. BC. Miron's original works have not reached us. They have to be judged by marble Roman copies.

Striving for the unity of the harmoniously beautiful and directly vital, Myron freed himself from the last echoes of archaic convention, from the angular sharpness of movements and at the same time from the sharp emphasis on details, which was sometimes resorted to by the masters of the second quarter of the 5th century. BC, who wanted in this way to give special truthfulness and naturalness to their statues. It is in the work of this Attic master that the Ionic and Doric artistic traditions finally merge. Miron became a master who synthesized in his work the main qualities of the realistic art of the early classics.

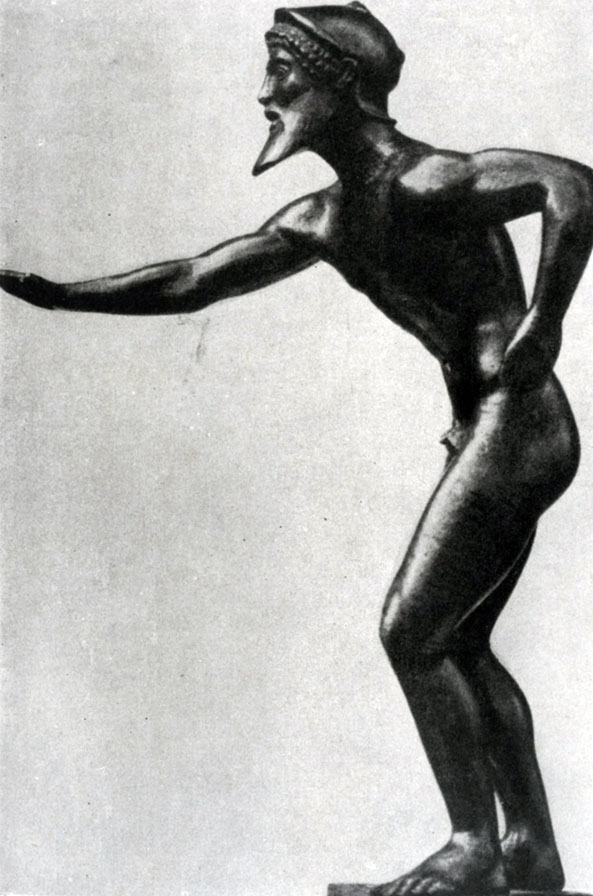

The peculiarities of Myron's art are expressed most forcefully in the Discus Thrower, described in the following terms by Lucian: “Are you not speaking of a discus thrower who bent in the motion of throwing, turned his head to look at his hand holding the discus, and slightly bent one leg, as if preparing to straighten up at the same time as the blow"( “Ancient poets about art”, M., 1938, p. 60.). Several not always accurate, and sometimes not completely preserved Roman copies of the famous statue of Myron have reached us. Of great interest is a bronze figurine from the 5th century. BC, depicting a discus thrower, apparently contemporary with the statue of Myron. The above photograph reproduces a cast that synthesizes the best Roman copies based on Lucian’s description.

The Disco Thrower, like many other statues of this type, was erected in honor of a specific person. The artist’s focus was on the task of depicting a strong and beautiful person in spirit and body, in intense and rapid movement. Myron depicted a discus thrower at the moment when he puts all his strength into throwing the discus. Despite the tension that permeates the figure, the statue gives the impression of stability. This is determined by the choice of the moment of movement: the moment of transition of one movement to another is taken, the culmination point in the development of movement.

Elastically bent over and firmly pressing his foot into the ground, the young man threw back his hand with the disk. Another moment, and the body, like a spring, will quickly straighten, the hand will forcefully throw the disk into space. A moment of peace gives monumental stability to the image, but in this moment the completed movement and the anticipation of all subsequent movement are combined, the hero’s action is embraced in all its completeness, in all its integrity. The concrete vitality of the movement is fused with a clear completeness, the integrity of the image, which was so close to the Greek aesthetic consciousness, which considered beautiful only that which clearly expressed the basic essence of the phenomenon. The composition of the statue reduces the complex and contradictory motive of movement to a few clear and vitally convincing gestures, giving a sense of concentrated, concentrated power. Despite the complexity of the movement, in the statue of the Discus Thrower, as in classical sculpture in general, a single point of view is preserved, allowing one to immediately see all the figurative richness of the statue.

Calm self-control, mastery over your feelings - characteristic Greek classical worldview, which determines the measure of a person’s ethical value. The images of Myron, as well as the design of the western Olympic pediment, grow on the same soil that back in the 6th century. BC. gave rise to the couplet:

Do not grieve too much in times of trouble and do not rejoice too much in times of happiness. Know how to carry both in your heart valiantly

The affirmation of the beauty of rational will, restraining the power of passion and giving its expression a form worthy of man, found its especially clear expression in Myron’s creation for Acropolis of Athens sculptural group “Athena and Marsyas”.

According to myth, Athena, among her various inventions aimed at benefiting people, created the double flute. But when she played it, she heard the laughter of other goddesses. Bending over the source, she saw in her reflection how her cheeks had swelled up ugly during the game. Athena threw the flute and cursed the instrument that violates the beautiful harmony of the human face. Silenus Marsyas, disregarding Athena’s curse, rushed to pick up the flute. Myron depicted the moment when Athena, leaving, turned angrily at the disobedient man, and Marsyas recoiled back in fear.